#NNPA BlackPress

Estevanico: The Man The Myth, The Legend

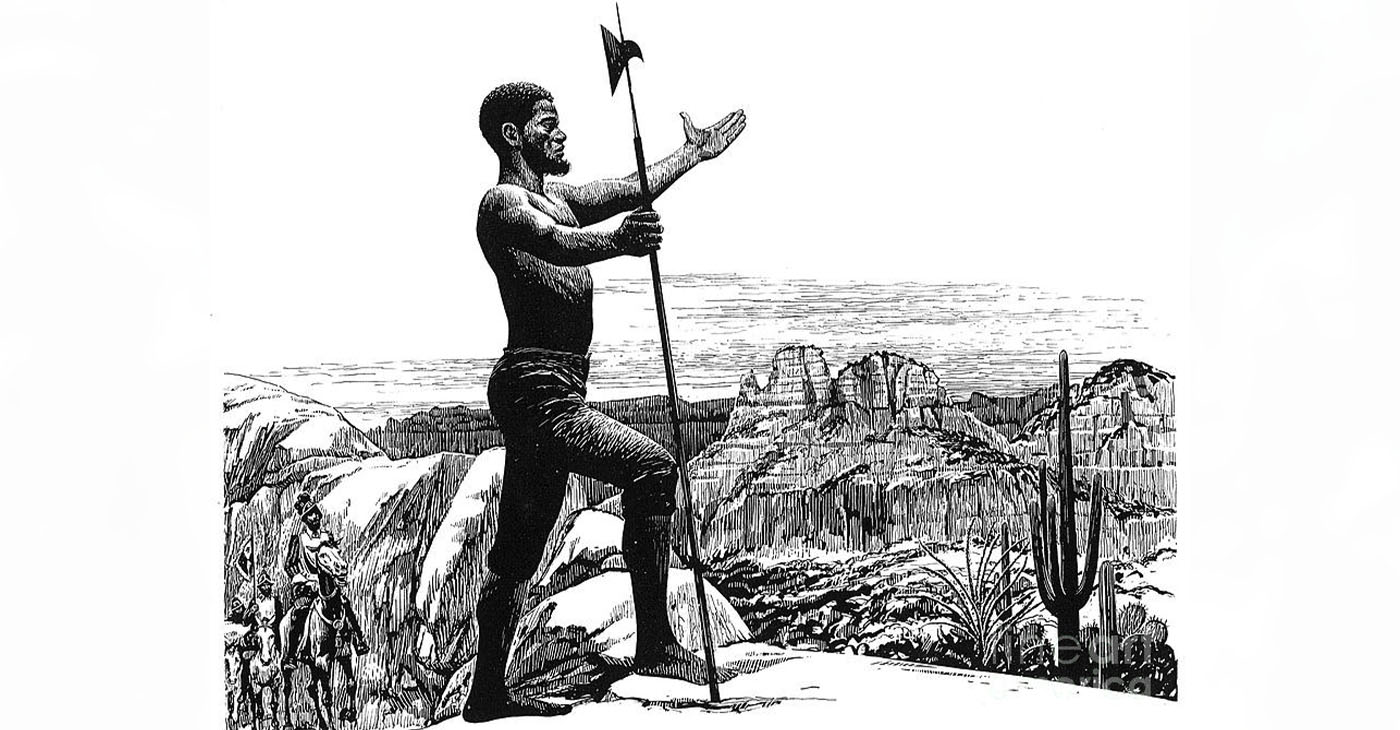

NNPA NEWSWIRE — Sometimes called “Mustafa Zemmouri,” “Black Stephen,” “Esteban the Moor” or “Steven Dorantes” (after his owner Andres Dorantes, a Spanish nobleman), Estevanico was a member of the Panfilo de Narvaez 300-man Spanish expedition which arrived in April 1528 near present-day Tampa Bay, Fla. The expedition was largely doomed from the start.

The post Estevanico: The Man The Myth, The Legend first appeared on BlackPressUSA.

The first Black person in the New World

By Merdies Hayes, Editor | Our Weekly

The history of slavery in the Western Hemisphere has, of course, been well documented but there is one name that is often overlooked in within the posterity of Black people in the New World: Estevanico.

Sometimes called “Mustafa Zemmouri,” “Black Stephen,” “Esteban the Moor” or “Steven Dorantes” (after his owner Andres Dorantes, a Spanish nobleman), Estevanico was a member of the Panfilo de Narvaez 300-man Spanish expedition which arrived in April 1528 near present-day Tampa Bay, Fla. The expedition was largely doomed from the start. This was not uncommon among the list of Spanish conquistadors who ventured to the New World seeking fertile land and untold riches imagined from the artful tales of Giovanni Verrazano who explored the northeast, Cabeza de Vaca in the Gulf of Mexico, Hernando Cortes in Mexico, Hernando de Soto near present-day Florida, and Francisco Pizarro far south in Peru.

Who was Estevanico?

Chroniclers from the 16th Century, who were contemporaries of Estevanico, considered him a Negro. However, modern historians claim he was descended from the Hamites who were White residents of North Africa. According to this theory, Estevanico could not have been Black. Historian Caroll L. Riley has asserted that Estevanico was “Black in the sense that we would use the word in modern America. Actually, in modern generic terms I suspect that Estevanico was very mixed.”

Riley also explained that if Estevanico was considered a “Negro,” his mixture must have been mainly Black. Estevanico in 1513 was sold into slavery to the Portuguese in the town of Azemmour, a Portuguese enclave on Morocco’s Atlantic coast. More contemporary accounts have referred to him as an “Arabized Black” or Moor, the latter term often used for Berber natives. History primarily refers to him as a Black African. A Spaniard, Diego de Guzman, reportedly saw Estevanico in 1536 and described him as “brown.”

Estevanico was reared as a Muslim—with some accounts of him converting to Roman Catholicism—but there is little historical account of his religious conversion.

The natives of one tiny island off the mainland coast (Galveston Island near Texas), encountered a strange sight in 1528: A band of emaciated White men lying naked and near dead on the beach. This group, in large part, was what was left from Narvaez’ expedition with de Vaca serving as its treasurer. Narvaez dreamed of riches when he reached the Florida coast and after finding mere traces of gold, he split the group and dispatched the ships toward the River of Palms (today’s Rio Grande) and took the land force toward a reportedly “rich” city brimming with gold and silver called Apalachen (near Tallahassee, Fla.).

A doomed expedition

Instead of finding their heart’s desire in wealth, the only things encountered in the Florida Panhandle were naked Native Indians, low supplies of food and even less game. The 260-man party lasted two weeks in this region, and eventually set out on makeshift boats with sails made from clothing. This was a fateful mistake. There was practically no food left or fresh water to drink. After constantly bailing water from their rickety crafts (and forced to drink salt water), only a few people survived and made it to shore. Narvaez was lost at sea.

Cortes, for his part, had listened faithfully to these “tales of riches” but found neither a queen called “Califia” nor gold and pearls along the west coast. He did, however, step ashore onto what he believed to be an island (Baja California) finding neither riches or fertile land, but would claim the land for the Spanish crown.

Cabeza de Vaca eventually made it to Mexico with only three men, among them Estevanico. There they recounted the horrors of slavery, starvation, cannibalism and disease which took the lives of 90 men. They reportedly posed as shamans, crossing the land curing sick Indians and attracting quite a following in being labeled “children of the sun” because of their long journey from the east. By the spring of 1529, those four men had traveled on foot along the Texas coast to the environs of Matagorda Bay (about 80 miles northeast of Corpus Christi) only to be captured and enslaved by the Coahuiltecan Indians. Six years later the four men managed to escape their bondage and entered Mexico.

Arriving in Texas

Estevanico was assuredly the first African to traverse Texas. In fact, historians believe he was the first African to visit the indigenous people of Mexico and may have reminded the inhabitants of the ancient sculptures of the Olmec civilization in Mesoamerica (1200-900 B.C.) which depicted persons with Black facial features. Estevanico, by extension, may have been considered by the native population as a descendant of the gods. Some writers have claimed that the Olmecs were related to the peoples of Africa, based primarily on their interpretations of said facial features, even contending that epigraphical and osteological evidence may support their claims. Further, some researchers have claimed that the Mesoamerican writing systems are related to African script. To date, however, genetic and immunological studies over the decades have failed to yield evidence of precolumbian African contributions to the indigenous populations of the Americas.

By 1539, Dorantes had either sold or loaned Estevanico to Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, who later assigned him to the company of Fray Marcos de Niza, the latter charged with leading a follow-up trip to the region of the failed Narvaez expedition. In a strange coincidence, Estevanico and others were surprised to encounter de Vaca near present-day San Antonio, Texas. By then, de Vaca had been working as a trader among the various Native Indian tribes. They resided in that region for about four years with Estevanico working as a shaman or medicine man versed in several Native Indian languages and also demonstrating his prowess as a seasoned explorer.

Estevanico must have been a strange sight to the native peoples. He rode around with a special gourd trimmed with owl feathers that signified his status. He reportedly had an entourage of some 300 natives, kept two Castillian greyhounds as pets, and possessed a special “medicine” wand with bells affixed to it said to ward off (and supposedly cure) various diseases. He also carried with him special plates made of turquoise specifically for his meals. He even had a special lodging constructed fit for a man of his stature.

Dreams of untold riches

Like the others before him, Estevanico was consumed by discovering the Seven Cities of Gold. His ultimate goal was to reach one of the seven famed cities of Cibola (near modern Zuni, NM) which was said to have streets paved with gold. When Estevanico and his entourage arrived at Hawikuh, a Zuni pueblo made of stone buildings several stories high, he expected to be treated as the man of stature he’d become accustomed to.

But the Zuni’s didn’t trust him. They especially disapproved of his gourd covered with owl feathers which were a symbol of death to that tribe. Also, his rather unusual stories about great White kings from far away further drew suspicion among the Zuni tribal leaders. There are two general accounts surrounding the fate of Estevanico. In one scenario, the Zuni people decided he was a spy (or simply a fraud) and killed him. Some accounts contend that he offended the Zuni people so much that they staged three executions eventually cutting up his body into little pieces. A second theory is that the Zunis didn’t kill him and that Estevanico staged his own death with the help of his allies, therefore finally gaining his freedom from slavery. The latter theory is supported by the fact that his body was never found.

His mysterious demise

The Zunis were asked why they killed Estevanico and they said that he claimed a huge army was following him with weapons meant to kill their tribe. Several of his Native Indian escorts reportedly escaped from the Zunis and returned to Mexico to inform Fray Marcos that Estevanico was dead. In his report to Viceroy Mendoza, Marcos said that he continued to travel north to at last enter Cibola (or Hawikuh) and upon arrival he witnessed a chief with Estevanico’s turquoise dinner plates, his two greyhound dogs, and his famed “medicine” bells.

Irrespective of his demise, Estevanico is one of many historical figures of color who manipulated their situation to move between cultures and transcend their humble beginnings. His is a true story of transformation from a slave to a man of legend evidenced by the Zunis memorializing him in a black ogre kachina (a doll measuring about a foot high with protruding teeth, a black goatee and black facial paint) which they called Chakwaina.

A legendary adventure

The tale of Estevanico is more than a story told in the oral tradition. Often, the history and contributions to society by Black persons prior to European settlement in the New World are considered less authentic and reliable in terms of literary content because it was believed Blacks did not ascribe to a written language. Estevanico did not write a diary or narrative of his exploits.

However, two small thin volumes of literature provide a wealth of information about this early explorer. John Upton Terrell published “Estevanico The Black” in 1968 and at only 115 pages, it ranks as one of the most informative books about an extraordinary figure who doesn’t always receive due attention in secondary education. In 1974, “Estebanico” was issued by Helen Rand Parish. Even smaller than Terrell’s book at 128 pages, she wrote that Estevanico could be considered “new historical history” particularly for young readers.

Also, “The Moor’s Account” by Laila Lalami (2015) provides a more fictional account of Estevanico. The author created her own back story about the events that led up to his enslavement and then fills in gaps of what we know about the Narvaez expedition that would eventually place Estevancio’s name in the history books.

No one knows where Estevanico is buried. Hawikuh no longer exists, having been abandoned in 1670 following a series of wars the Zunis fought against the Spaniards and the Apache. But Estevanico’s story, recorded in colorful detail by his fellow explorers Cabeza de Vaca, Fray Marcos, Coronado, and Pedro de Casteneda, endures as one of the great adventures in American lore.

The post Estevanico: The Man The Myth, The Legend first appeared on BlackPressUSA.

#NNPA BlackPress

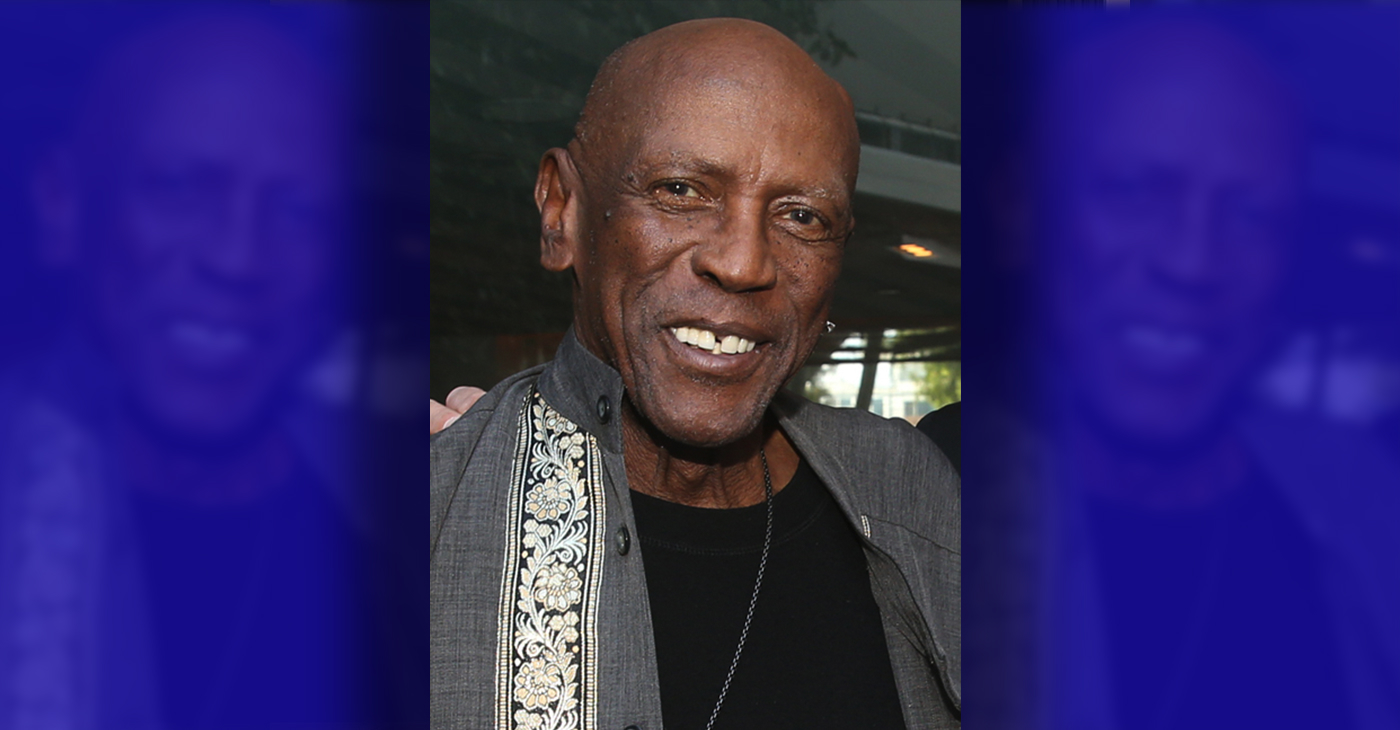

Beloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

NNPA NEWSWIRE — Louis Gossett Jr., the groundbreaking actor whose career spanned over five decades and who became the first Black actor to win an Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor for his memorable role in “An Officer and a Gentleman,” has died. Gossett, who was born on May 27, 1936, in Brooklyn, N.Y., was 87. Recognized early on for his resilience and nearly unmatched determination, Gossett arrived in Los Angeles in 1967 after a stint on Broadway.

The post Beloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87 first appeared on BlackPressUSA.

By Stacy M. Brown

NNPA Newswire Senior National Correspondent

@StacyBrownMedia

Louis Gossett Jr., the groundbreaking actor whose career spanned over five decades and who became the first Black actor to win an Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor for his memorable role in “An Officer and a Gentleman,” has died. Gossett, who was born on May 27, 1936, in Brooklyn, N.Y., was 87. Recognized early on for his resilience and nearly unmatched determination, Gossett arrived in Los Angeles in 1967 after a stint on Broadway.

He sometimes spoke of being pulled over by law enforcement en route to Beverly Hills, once being handcuffed to a tree, which he remembered as a jarring introduction to the racial tensions of Hollywood. In his memoir “An Actor and a Gentleman,” Gossett recounted the ordeal, noting the challenges faced by Black artists in the industry. Despite the hurdles, Gossett’s talent shone brightly, earning him acclaim in groundbreaking productions such as “A Raisin in the Sun” alongside Sidney Poitier. His Emmy-winning portrayal of Fiddler in “Roots” solidified his status as a trailblazer, navigating a landscape fraught with racial prejudice.

According to the HistoryMakers, which interviewed him in 2005, Gossett’s journey into the limelight began during his formative years at PS 135 and Mark Twain Junior High School, where he demonstrated early leadership as the student body president. His passion for the arts blossomed when he starred in a “You Can’t Take It With You” production at Abraham Lincoln High School, catching the attention of talent scouts who propelled him onto Broadway’s stage in “Take A Giant Step.” His stellar performance earned him the prestigious Donaldson Award for Best Newcomer to Theatre in 1952. Though initially drawn to sports, Gossett’s towering 6’4” frame and athletic prowess led him to receive a basketball scholarship at New York University. Despite being drafted by the New York Knicks in 1958, Gossett pursued his love for acting, honing his craft at The Actors Studio under the tutelage of luminaries like John Sticks and Peggy Fury.

In 1961, Gossett’s talent caught the eye of Broadway directors, leading to roles in acclaimed productions such as “Raisin in the Sun” and “The Blacks,” alongside legends like James Earl Jones, Cicely Tyson, Roscoe Lee Brown, and Maya Angelou. Transitioning seamlessly to television, Gossett graced small screens with appearances in notable shows like “The Bush Baby” and “Companions in Nightmare.” Gossett’s silver screen breakthrough came with his role in “The Landlord,” paving the way for a prolific filmography that spanned over 50 movies and hundreds of television shows. From “Skin Game” to “Lackawanna Blues,” Gossett captivated audiences with his commanding presence and versatile performances.

However, his portrayal of “Fiddler” in Alex Haley’s groundbreaking miniseries “Roots” earned Gossett critical acclaim, including an Emmy Award. The HistoryMakers noted that his golden touch extended to the big screen, where his role as Sergeant Emil Foley in “An Officer and a Gentleman” earned him an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, making him a trailblazer in Hollywood history.

Beyond the glitz and glamour of Hollywood, Gossett was deeply committed to community activism. In 1964, he co-founded a theater group for troubled youth alongside James Earl Jones and Paul Sorvino, setting the stage for his lifelong dedication to mentoring and inspiring the next generation. Gossett’s tireless advocacy for racial equality culminated in the establishment of Eracism, a nonprofit organization dedicated to combating racism both domestically and abroad. Throughout his illustrious career, Gossett remained a beacon of strength and resilience, using his platform to uplift marginalized voices and champion social change. Gossett is survived by his children, Satie and Sharron.

The post Beloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87 first appeared on BlackPressUSA.

#NNPA BlackPress

COMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

WASHINGTON INFORMER — The D.C. crime bill and so many others like it are reminiscent of the ‘94 crime bill, which produced new and harsher criminal sentences, helped deploy thousands of police and surveilling methods in Black and brown communities, and incentivized more states to build prisons through a massive infusion of federal funding. While it is not at the root of mass incarceration, it significantly accelerated it, forcing a generation of Black and brown families into a never-ending cycle of state-sanctioned violence and incarceration.

The post COMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration first appeared on BlackPressUSA.

By Kaili Moss and Jillian Burford | Washington Informer

Mayor Bowser has signed the “Secure DC” omnibus bill passed by the D.C. Council last month. But we already know that this bill will be disastrous for all of D.C., especially for Black and brown residents.

While proponents claim that this legislation “will make D.C. residents safer and more secure,” it actually does nothing to address the root of the harm in the first place and instead maintains a cycle of violence, poverty, and broken community ties. The omnibus bill calls for increased surveillance, drug-free zones, and will expand pre-trial detention that will incarcerate people at a significantly higher rate and for an indeterminate amount of time before they are even tried. This bill will roll back decades of nationwide policy reform efforts and initiatives to keep our communities safe and whole, which is completely contradictory to what the “Secure” D.C. bill claims it will do.

What is unfolding in Washington, D.C., is part of a dangerous national trend. We have seen a resurrection of bad crime bills in several jurisdictions across the country — a phenomenon policy experts have named “zombie laws,” which are ineffective, costly, dangerous for communities of color and, most importantly, will not create public safety. Throwing more money into policing while failing to fund preventative measures does not keep us safe.

The D.C. crime bill and so many others like it are reminiscent of the ‘94 crime bill, which produced new and harsher criminal sentences, helped deploy thousands of police and surveilling methods in Black and brown communities, and incentivized more states to build prisons through a massive infusion of federal funding. While it is not at the root of mass incarceration, it significantly accelerated it, forcing a generation of Black and brown families into a never-ending cycle of state-sanctioned violence and incarceration. Thirty years later, despite spending billions each year to enforce these policies with many of these provisions remaining in effect, it has done very little to create long-term preventative solutions. Instead, it placed a permanent moving target on the backs of Black people, and the D.C. crime bill will do the same.

The bill calls for more pretrial detention. When our loved ones are held on pretrial detention, they are held on the presumption of guilt for an indeterminate amount of time before ever seeing a judge, which can destabilize people and their families. According to experts at the Malcolm Weimer Center for Social Policy at Harvard University, just one day in jail can have “devastating consequences.” On any given day, approximately 750,000 people are held in jails across the nation — a number that beats our nation’s capital population by about 100,000. Once detained, people run the risk of losing wages, jobs, housing, mental and health treatments, and time with their families. Studies show that pretrial detention of even a couple of days makes it more likely for that person to be rearrested.

The bill also endangers people by continuing a misguided and dangerous War on Drugs, which will not get drugs off the street, nor will it deter drug use and subsequent substance use disorders (SUDs). Drug policies are a matter of public health and should be treated as such. Many states such as Alabama, Iowa and Wisconsin are treating the current fentanyl crisis as “Crack 2.0,” reintroducing a litany of failed policies that have sent millions to jails and prisons instead of prioritizing harm reduction. Instead, we propose a simple solution: listen to members of the affected communities. Through the Decrim Poverty D.C. Coalition, community members, policy experts and other stakeholders formed a campaign to decriminalize drugs and propose comprehensive legislation to do so.

While there are many concerning provisions within the omnibus bill, car chases pose a direct physical threat to our community members. In July 2023, NBC4 reported that the D.C. Council approved emergency legislation that gave MPD officers the ability to engage in vehicular pursuits with so-called “limited circumstances.” Sgt. Val Barnes, the head of MPD’s carjacking task force, even expressed concern months before the decision, saying, “The department has a pretty strict no-chase policy, and obviously for an urban setting and a major metropolitan city, that’s understandable.” If our law enforcement officers themselves are operating with more concern than our elected officials, what does it say about the omnibus bill’s purported intention to keep us safe?

And what does it mean when the risk of bodily harm is posed by the pursuit itself? On Saturday, Feb. 10, an Eckington resident had a near-miss as a stolen car barreled towards her and her dog on the sidewalk with an MPD officer in pursuit. What responsibility does the city hold if this bystander was hit? What does restitution look like? Why are our elected officials pushing for MPD officers to contradict their own policies?

Just a few summers ago during the uprisings of 2020, we saw a shift in public perspectives on policing and led to legislation aimed at limiting police power after the highly-publicized murders of loved ones Breonna Taylor and George Floyd — both victims of War on Drugs policing and the powers gained from the ’94 crime bill. And yet here we are. These measures do not keep us safe and further endanger the health of our communities. Studies show that communities that focus on harm reduction and improving material conditions have a greater impact on public safety and community health. What’s missing in mainstream conversations about violent crime is the violence that stems from state institutions and structures that perpetuate racial and class inequality. The people of D.C. deserve to feel safe, and that includes feeling safe from the harms enacted by the police.

Kaili Moss is a staff attorney at Advancement Project, a national racial justice and legal organization, and Jillian Burford is a policy organizer at Harriet’s Wildest Dreams.

The post COMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration first appeared on BlackPressUSA.

#NNPA BlackPress

Mayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

THE BIRMINGHAM TIMES — “This is a tragic day for the college, our students, our employees, and our alumni, and an outcome so many have worked tirelessly to prevent,” Rev. Keith Thompson, chairman of the BSC Board of Trustees said in an announcement to alumni. “We understand the devastating impact this has on each of you, and we will now direct our efforts toward ensuring the smoothest possible transition for everyone involved.”

The post Mayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College first appeared on BlackPressUSA.

By Barnett Wright | The Birmingham Times

Birmingham-Southern College will close on May 31, after more than a century as one of the city’s most respected institutions.

“This is a tragic day for the college, our students, our employees, and our alumni, and an outcome so many have worked tirelessly to prevent,” Rev. Keith Thompson, chairman of the BSC Board of Trustees said in an announcement to alumni. “We understand the devastating impact this has on each of you, and we will now direct our efforts toward ensuring the smoothest possible transition for everyone involved.”

There are approximately 700 students enrolled at BSC this semester.

“Word of the decision to close Birmingham Southern College is disappointing and heartbreaking to all of us who recognize it as a stalwart of our community,” Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin said in a statement. “I’ve stood alongside members of our City Council to protect this institution and its proud legacy of shaping leaders. It’s frustrating that those values were not shared by lawmakers in Montgomery.”

Birmingham City Council President Darrell O’Quinn said news of the closing was “devastating” on multiple levels.

“This is devastating for the students, faculty members, families and everyone affiliated with this historic institution of higher learning,” he said. “It’s also profoundly distressing for the surrounding community, who will now be living in close proximity to an empty college campus. As we’ve seen with other institutions that have shuttered their doors, we will be entering a difficult chapter following this unfortunate development … We’re approaching this with resilience and a sense of hope that something positive can eventually come from this troubling chapter.”

The school first started as the merger of Southern University and Birmingham College in 1918.

The announcement comes over a year after BSC officials admitted the institution was $38 million in debt. Looking to the Alabama Legislature for help, BSC did not receive any assistance.

This past legislative session, Sen. Jabo Waggoner sponsored a bill to extend a loan to BSC. However, the bill subsequently died on the floor.

Notable BSC alumni include former New York Times editor-in-chief Howell Raines, former U.S. Sen. Howell Heflin and former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Perry O. Hooper Sr.

This story will be updated.

The post Mayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College first appeared on BlackPressUSA.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 20 – 26, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: Lady Day and The Lights!

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoFrom Raids to Revelations: The Dark Turn in Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs’ Saga

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoBaltimore Key Bridge Catastrophe: A City’s Heartbreak and a Nation’s Alarm

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoBaltimore’s Key Bridge Struck by Ship, Collapses into Water