Activism

Kwanzaa: Celebrating More Than 7 Principles

Some people think of Kwanzaa as an alternative to Christmas, referring to it as Black Christmas. Karenga writes that Kwanzaa is not a religious holiday, but one that is cultural “with an inherent spiritual quality. Thus, Africans of all faiths can and do celebrate Kwanzaa.” This, Karenga says, includes Muslims, Christians, Black Hebrews, Jews, Buddhists, Baháʼí, and Hindus, as well as those who follow the ancient traditions of Maat, Yoruba, Ashanti, Dogon.

By Tamara Shiloh

Millions of people worldwide participate in Kwanzaa, celebrated from December 26 to January 1. Modeled after traditional African harvest festivals, the name of this holiday was borrowed from the Swahili phrase matunda ya kwanza, meaning “first fruits.”

More than 2,000 languages are spoken in Africa. Swahili is one of its more unifying languages, spoken by millions on the continent.

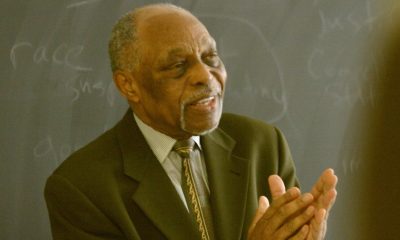

Maulana Ndabezitha Karenga, activist and American professor of Africana studies, created the pan-African holiday. He did so as a way of uniting and empowering the Black community in the aftermath of the Watts Rebellion, or the Watts Riots, which broke out on Aug. 11, 1965, in Los Angeles.

Prompted by a Black man’s altercation with police, the riots lasted six days, leaving 34 dead, 1,032 injured. There were 4,000 arrests and more than 1,000 buildings destroyed, totaling $40 million in damages.

The first celebration was held in 1966. Seven children attended, each representing a letter in the word Kwanzaa, hence Karenga’s addition of the letter ‘a’ to the traditional Swahili spelling of kwanza.

Some people think of Kwanzaa as an alternative to Christmas, referring to it as Black Christmas. Karenga writes that Kwanzaa is not a religious holiday, but one that is cultural “with an inherent spiritual quality. Thus, Africans of all faiths can and do celebrate Kwanzaa.” This, Karenga says, includes Muslims, Christians, Black Hebrews, Jews, Buddhists, Baháʼí, and Hindus, as well as those who follow the ancient traditions of Maat, Yoruba, Ashanti, Dogon.

Kwanzaa, modeled after the first harvest celebrations in Africa, is rooted in African culture. However, people from all racial and ethnic backgrounds are welcome to join in the celebration of its principles.

Part of the tradition is gift-giving on the last day. Because the holiday is a celebration of spiritual qualities and not commercialization, handmade or educational gifts, such as books, puzzles, or culturally themed items, are encouraged.

Activities held throughout the week embrace five central values: ingathering, reverence, commemoration, recommitment, and celebration. From these, one of the seven principles, or nguzo saba, are celebrated each day: umoja (unity), kujichagulia (self-determination), ujima (collective work and responsibility), ujamaa (cooperative economics), nia (purpose), kuumba (creativity), and imani (faith).

The mishumaa saba (seven candles) are set in candleholder called a kinara. The candles boast the colors of the pan-African flag designed by Marcus Garvey: black for the people, red for the noble blood that unites all people of African ancestry, and green for the rich land of Africa. The lone black candle stands for unity. The three green candles represent the future, and three red candles represent the struggle out of slavery. Each night one candle on the Kinara is lit in honor of the day’s principle.

Although Kwanzaa is not widely celebrated in Africa, it is publicly acknowledged in the Caribbean as well as other cities where there are large numbers of descendants of Africans such as London, Paris, and Toronto. Such a prideful event honoring family, culture, and heritage should be reflected upon year-round.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Schools Honor Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice. His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

By Post Staff

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice.

His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

One OUSD school is named in his honor: Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy (KDA) elementary in East Oakland.

Several years ago, founding KDA Principal Charles Wilson, in a video interview with anti-hate organization “Not In Our Town,” said, “We chose the name Fred Korematsu because we really felt like the attributes that he showed in his work are things that the children need to learn … that common people can stand up and make differences in a large number of people’s lives.”

Fred Korematsu was born in Oakland on Jan. 30, 1919. His parents ran a floral nursery business, and his upbringing in Oakland shaped his worldview. His belief in the importance of standing up for your rights and the rights of others, regardless of race or background, was the foundation for his activism against racial prejudice and for the rights of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the start of the war, Korematsu was turned away from enlisting in the National Guard and the Coast Guard because of his race. He trained as a welder, working at the docks in Oakland, but was fired after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Fear and prejudice led to federal Executive Order 9066, which forced more than 120,000 Japanese Americans out of their homes and neighborhoods and into remote internment camps.

The 23-year-old Korematsu resisted the order. He underwent cosmetic surgery and assumed a false identity, choosing freedom over unjust imprisonment. His later arrest and conviction sparked a legal battle that would challenge the foundation of civil liberties in America.

Korematsu’s fight culminated in the Supreme Court’s initial ruling against him in 1944. He spent years in a Utah internment camp with his family, followed by time living in Salt Lake City where he was dogged by racism.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford overturned Executive Order 9066. Seven years later, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco vacated Korematsu’s conviction. He said in court, “I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong and do something about it so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color.”

Korematsu’s dedication and determination established him as a national icon of civil rights and social justice. He advocated for justice with Rosa Parks. In 1998, President Bill Clinton gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom saying, “In the long history of our country’s constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls … To that distinguished list, today we add the name of Fred Korematsu.”

After Sept. 11, 2001, Korematsu spoke out against hatred and discrimination, saying what happened to Japanese Americans should not happen to people of Middle Eastern descent.

Korematsu’s roots in Oakland and his education in OUSD are a source of great pride for the city, according to the school district. His most famous quote, which is on the Korematsu elementary school mural, is as relevant now as ever, “If you have the feeling that something is wrong, don’t be afraid to speak up.”

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoAG Bonta Says Oakland School Leaders Should Comply with State Laws to Avoid ‘Disparate Harm’ When Closing or Merging Schools

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoOakland WNBA Player to be Inducted Into Hall of Fame

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoThe Year Ahead: Assembly Speaker Rivas Discusses Priorities, Problems

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoRichmond Nonprofit Helps Ex-Felons Get Back on Their Feet