Activism

MLK: Letter from Birmingham Jail

It was a King supporter who smuggled the nearly 7,000 written words, handing them over to King’s lawyers. The letter was then transcribed and printed partially or in full in several publications including the New York Post, Liberation magazine, The New Leader, and The Christian Century. It was also published by The Atlantic (August 1963) under the title “The Negro Is Your Brother.”

By Tamara Shiloh

The year was 1963. Cries for equality and an end to injustice for Blacks in Birmingham, Ala., were silenced by the city’s mayor Eugene “Bull” Connor. Alabama Governor George Wallace, stood on the steps of the state capitol and declared: “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” This became the motto for those opposed to integration and the Civil Rights Movement.

Bombings targeting leaders of the Birmingham campaign triggered the Birmingham riot. Klan-led violence went unchecked. Massive protests for civil rights grew stronger.

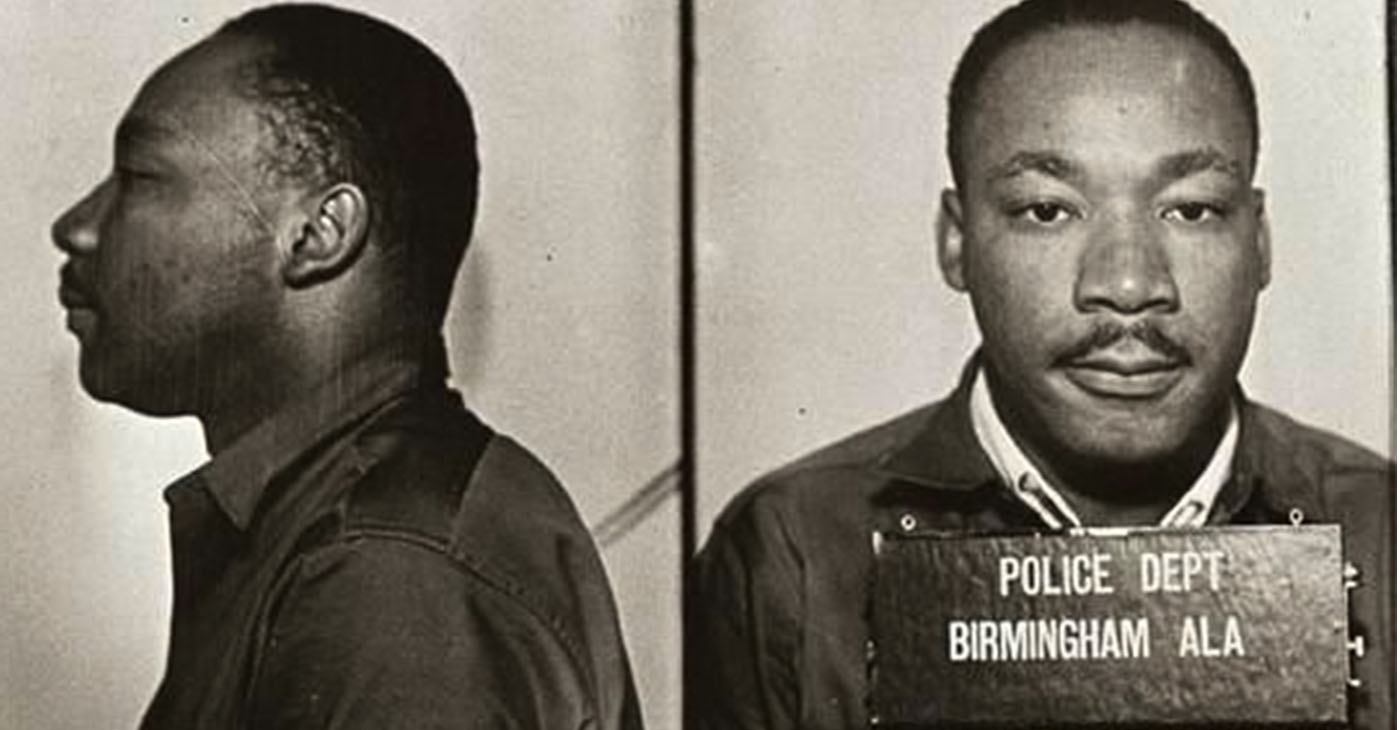

In April, Martin Luther King Jr. wrote from a cell in the city’s jail: “Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known.”

These exact words targeted Birmingham for the next phase in the struggle for equality. A change that no one could have predicted was coming.

King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference had joined with Birmingham’s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR). Their collective goal was to form a direct-action campaign that would cripple the city’s segregation system.

The city’s merchants would be under economic pressure if Blacks refused to patronize them during the Easter season. ACMHR Founder Fred Shuttlesworth described the campaign as “a moral witness to give our community a chance to survive.”

Despite a state court’s injunction and absence of a permit, King led the Easter boycott of white-owned stores peacefully on Good Friday. He was arrested by local police along with Ralph Abernathy and a few other protesters.

During the eight days of solitary confinement, King began to pen his response to white ministers who questioned why he and protesters had chosen to stage their protests in Birmingham. He did so on the margins of the Birmingham News.

It was a King supporter who smuggled the nearly 7,000 written words, handing them over to King’s lawyers. The letter was then transcribed and printed partially or in full in several publications including the New York Post, Liberation magazine, The New Leader, and The Christian Century. It was also published by The Atlantic (August 1963) under the title “The Negro Is Your Brother.”

Those pieces of paper had become the “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” the most important written document of the Civil Rights era of the time. It is one of the most famous defenses of nonviolent action against racism.

While incarcerated, King’s request for a phone call to Coretta Scott King had been denied. Coretta contacted the Kennedy administration, forcing Birmingham officials to permit the call. Bail money was made available, and King was released on April 20.

The Birmingham campaign was successful. Local officials removed White Only and Colored Only signs from restrooms and drinking fountains in downtown Birmingham, desegregated lunch counters, released demonstrators who were jailed, deployed a Negro job improvement plan, and created a biracial committee to monitor the agreement

Desegregation was slow, but change had finally arrived in what was once known as “the most segregated city in America.”

To listen to the letter in its entirety: “Martin Luther King Letter from Birmingham Jail,” by MLK.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Schools Honor Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice. His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

By Post Staff

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice.

His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

One OUSD school is named in his honor: Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy (KDA) elementary in East Oakland.

Several years ago, founding KDA Principal Charles Wilson, in a video interview with anti-hate organization “Not In Our Town,” said, “We chose the name Fred Korematsu because we really felt like the attributes that he showed in his work are things that the children need to learn … that common people can stand up and make differences in a large number of people’s lives.”

Fred Korematsu was born in Oakland on Jan. 30, 1919. His parents ran a floral nursery business, and his upbringing in Oakland shaped his worldview. His belief in the importance of standing up for your rights and the rights of others, regardless of race or background, was the foundation for his activism against racial prejudice and for the rights of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the start of the war, Korematsu was turned away from enlisting in the National Guard and the Coast Guard because of his race. He trained as a welder, working at the docks in Oakland, but was fired after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Fear and prejudice led to federal Executive Order 9066, which forced more than 120,000 Japanese Americans out of their homes and neighborhoods and into remote internment camps.

The 23-year-old Korematsu resisted the order. He underwent cosmetic surgery and assumed a false identity, choosing freedom over unjust imprisonment. His later arrest and conviction sparked a legal battle that would challenge the foundation of civil liberties in America.

Korematsu’s fight culminated in the Supreme Court’s initial ruling against him in 1944. He spent years in a Utah internment camp with his family, followed by time living in Salt Lake City where he was dogged by racism.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford overturned Executive Order 9066. Seven years later, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco vacated Korematsu’s conviction. He said in court, “I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong and do something about it so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color.”

Korematsu’s dedication and determination established him as a national icon of civil rights and social justice. He advocated for justice with Rosa Parks. In 1998, President Bill Clinton gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom saying, “In the long history of our country’s constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls … To that distinguished list, today we add the name of Fred Korematsu.”

After Sept. 11, 2001, Korematsu spoke out against hatred and discrimination, saying what happened to Japanese Americans should not happen to people of Middle Eastern descent.

Korematsu’s roots in Oakland and his education in OUSD are a source of great pride for the city, according to the school district. His most famous quote, which is on the Korematsu elementary school mural, is as relevant now as ever, “If you have the feeling that something is wrong, don’t be afraid to speak up.”

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoAG Bonta Says Oakland School Leaders Should Comply with State Laws to Avoid ‘Disparate Harm’ When Closing or Merging Schools

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoOakland WNBA Player to be Inducted Into Hall of Fame