Book Reviews

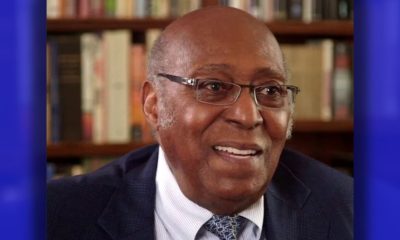

“Lucky Medicine” by Lester W. Thompson

It didn’t arrive in a package. It wasn’t wrapped in fancy paper. It didn’t arrive with cake or candles. And yet, the gift you got, that thing that someone gave you was better than anything that could’ve come in a pretty box. It was bigger than you ever expected. As in the new memoir, “Lucky Medicine” by Lester W. Thompson, the gift was a life-changer.

c.2023, Well House Books, Indiana University Press $24.00 196 pages

It didn’t arrive in a package.

It wasn’t wrapped in fancy paper. It didn’t arrive with cake or candles. And yet, the gift you got, that thing that someone gave you was better than anything that could’ve come in a pretty box. It was bigger than you ever expected. As in the new memoir, “Lucky Medicine” by Lester W. Thompson, the gift was a life-changer.

Born and raised in Indianapolis, Lester Thompson grew up with “rules” that his Southern-born parents instilled in him all his life. Even though Jim Crow racism wasn’t entrenched in the North like it was in the South, such rules were “the frame of reference.”

And that lent mystery to a very curious relationship Thompson’s father had with a white Jewish man, Mr. Goodman. Cal Thompson cut Goodman’s hair in the privacy of Goodman’s home; Thompson sometimes accompanied his father there, but he never fully understood the friendship between the two men. He says “It didn’t occur to me to wonder…”

When he was thirteen, he learned the truth: he was named after Goodman, who was his father’s closest friend. Furthermore, Goodman was Thompson’s godfather and he’d made a vow to pay for Thompson’s entire college education.

That he was going to be a doctor someday was another thing Thompson had known all his life. His father, an authoritarian alcoholic, never left any room to question it. And so, after high school graduation, Thompson headed to IU in Bloomington, Indiana.

It was an eye-opener, in many ways.

An only child, Thompson had to learn how to share. He had to learn to live with white people next door, and how to study for classes that seemed impossible to ace. He fell in love, and fell again. And he watched the world change as the Civil Rights Movement began.

“I will never know what prompted Mr. Goodman to make his gift,” Thompson says. “But in the end, I suppose, all that matters is that he did.”

Sometimes, change can come with a big ka-BOOM. Other times, it sneaks in the back door and sits quietly. That mixture’s what you get with this unique memoir, “Lucky Medicine.”

Unique because while racism figures into author Lester W. Thompson’s story, it’s not a very big part, considering the mid-last-century setting. The Movement is barely a blip on the radar; only a handful of troubles with white people are mentioned, and they’re not belabored. So, racism is in this book, but only at whisper-level.

Instead, Thompson focuses on his relatively insulated life, his parents and friends, his studies, and the mysterious, still-unsolved relationship his father had with Goodman. And that’s where this story glows: Thompson’s tale is nostalgic and mundane. It’s not overly dramatic. It doesn’t shout or beg for attention. It’s just warm and happily, wonderfully, ordinary.

Be aware before you share this book with an elder that there are four-letter words in here and a rather eyebrow-raising, too-much-information bedroom scene inside. If you can handle that, though, “Lucky Medicine” is a one-of-a-kind gift.

Book Reviews

Book Review: Books for Poetry Month by Various Authors

Picture books for the littles are a great way to introduce your 3-to7-year-old to poetry because simple stories lend themselves to gentle rhymes and lessons. “See You on the Other Side” by Rachel Montez Minor, illustrated by Mariyah Rahman (Crown, $18.99) is a rhyming book about love and loss, but it’s not as sad as you might think.

c.2023, 2024, Various Publishers

$18.99 – $20.00

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

On your hands, you have lots of time.

You can make a song, or you can make a rhyme. Make a long story, make a short one, write what you like, make it simple and fun. Writing poetry uses your imagination: you play with words, paint a picture. There’s no intimidation. Creating poetry can be a breeze, or just reach for and read books exactly like these…

Picture books for the littles are a great way to introduce your 3-to7-year-old to poetry because simple stories lend themselves to gentle rhymes and lessons. “See You on the Other Side” by Rachel Montez Minor, illustrated by Mariyah Rahman (Crown, $18.99) is a rhyming book about love and loss, but it’s not as sad as you might think.

In this book, several young children learn that losing someone beloved is not a forever thing, that it is very sad but it’s not scary because their loved one is always just a thought away. Young readers who’ve recently experienced the death of a parent, grandparent, sibling, or friend will be comforted by the rhyme here, but don’t dismiss the words. Adults who’ve recently lost a loved one will find helpful, comforting words here, too.

Flitting from here to there and back again, author Alice Notley moves through phases of her life, locations, and her diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in her latest poetry collection, “Being Reflected Upon” (Penguin, $20.00). From 2000 to 2017, Notley lived in Paris where she wrestled with breast cancer. That, and her life abroad, are reflected in the poetry here; she also takes readers on a poetic journey on other adventures and to other places she lived and visited. This book has a random feel that entices readers to skip around and dive in anywhere. Fans of Notley will appreciate her new-age approach to her works; new fans will enjoy digging into her thoughts and visions through poems. Bonus: at least one of the poems may make you laugh.

If you’re a reader who’s willing to look into the future, “Colorfast” by Rose McLarney (Penguin, $20.00) will be a book you’ll return to time and again. This, the author’s fourth collection, is filled with vivid poems of graying and fading, but also of bright shades, small things, women’s lives yesterday and today, McLarney’s Southern childhood, and the things she recalls about her childhood. The poems inside this book are like sitting on a front porch in a wooden rocking chair: they’re comfortable, inviting, and they tell a story that readers will love discovering.

If these books aren’t enough, or if you’re looking for something different, silly, or classic, then head to your favorite bookstore or library. The ladies and gentlemen there will help you figure out exactly what you need, and they can introduce you to the kind of poetry that makes you laugh, makes you cry, entices a child, inspires you, gives you comfort, or makes you want to write your own poems. Isn’t it time to enjoy a rhyme?

Book Reviews

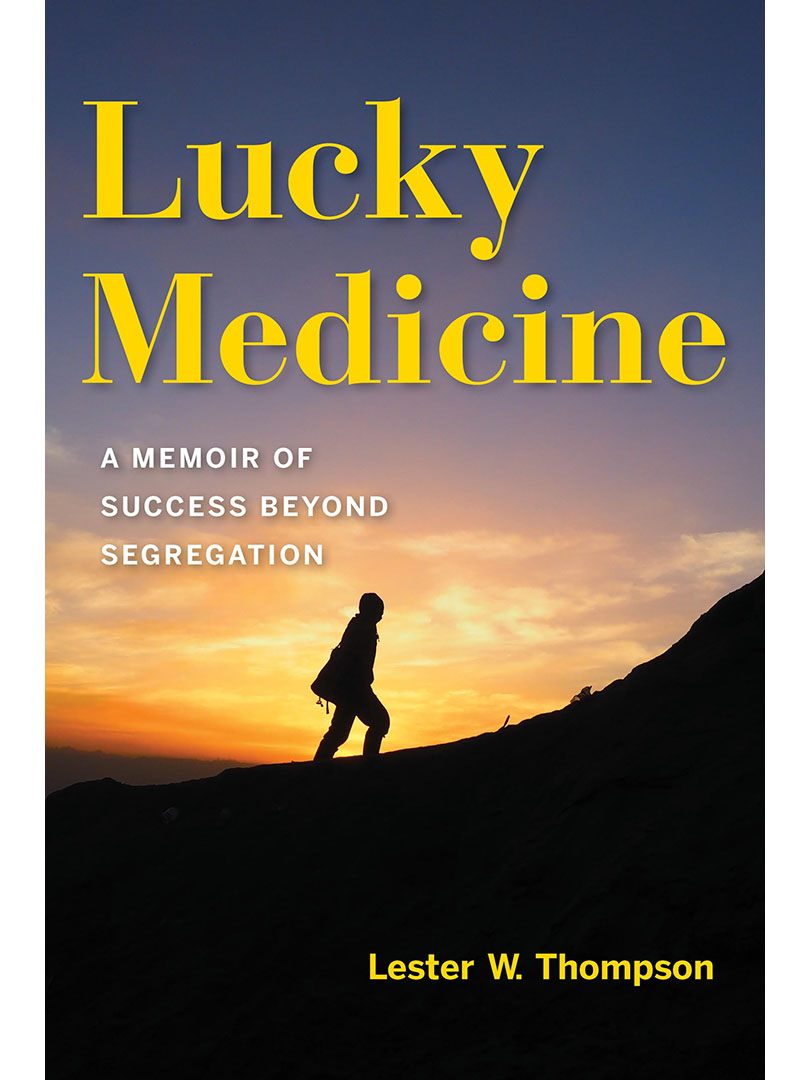

Book Review: “Dear Black Girls: How to Be True to You” by A’Ja Wilson

The envelope on the table is addressed to you. It caught your attention because — who, besides politicians, utilities, and creditors sends anything in the mail these days? Still, it was a nice surprise, no matter what, like a throwback or something. And like the new book, “Dear Black Girls” by A’Ja Wilson, every letter means something.

c.2024, Moment of Life Books /Flatiron Books

$24.99

192 pages

Photo Caption: Courtesy of A’Ja Wilson

The envelope on the table is addressed to you.

It caught your attention because — who, besides politicians, utilities, and creditors sends anything in the mail these days? Still, it was a nice surprise, no matter what, like a throwback or something. And like the new book, “Dear Black Girls” by A’Ja Wilson, every letter means something.

From the time she was born until she was in fourth or fifth grade, A’Ja Wilson lived in a bubble. She didn’t know it; she was only a kid, just being herself with no worries. And then, right before one of her best friends was having a birthday party, Wilson learned that the girl’s dad “really [didn’t] like Black people.” Those few words shook Wilson’s dad, they made her mother quietly angry, and they made Wilson doubt herself for many years.

It was her first reminder: “You’re a girl.

Oh! And you’re a Black girl.

Alright, good luck!”

With the help of her parents and her beloved grandmother, Wilson healed but she never forgot. She made sure to know her roots and her family’s story. She was dyslexic, so she struggled, tried to fit in, and grew taller than most boys, which didn’t help her self-esteem. Neither did the fact that at almost every point in her life, the color of her skin mattered in ways that it shouldn’t have mattered. That included her activity on a basketball court.

Wilson was a young teen when her father first threw her a ball and she hated it, but by the time she graduated from high school, she’d found her way. She’d developed a good “Nonsense Detector.” She got some therapy (“Ain’t no shame in it.”); she learned that when she did her best, there were still going to be haters; and she always remembered to be herself and to be a light for others.

Remember, she says, “You don’t have to be an WNBA player or a politician or a celebrity to have an impact on someone.”

So, will you learn a thing or two by reading “Dear Black Girls”?

Yes and no. In her short introduction, author A’Ja Wilson says that this “is not a self-help book,” and that it’s just “a diary of somebody… who looks like you…” Eh, that’s nothing new but despite her protests, “Dear Black Girls” is helpful. You just have to be ready for it.

That’s not hard; Wilson, a two-time WNBA MVP tells her story with a flair for fun. She even tells the sad tales with exuberance, subtly letting readers know that it’s okay, she’s okay, and it’s all just part of her story. Her voice lets you know how much she enjoys life, even when she has tough things to deal with. It’s like hearing encouragement from the top bunk, or getting straight talk from a mentor.

While it might seem to be a book for teenagers only, “Dear Black Girls” would also be a great resource for younger adults. Take a look, see if it doesn’t get your stamp of approval.

Book Reviews

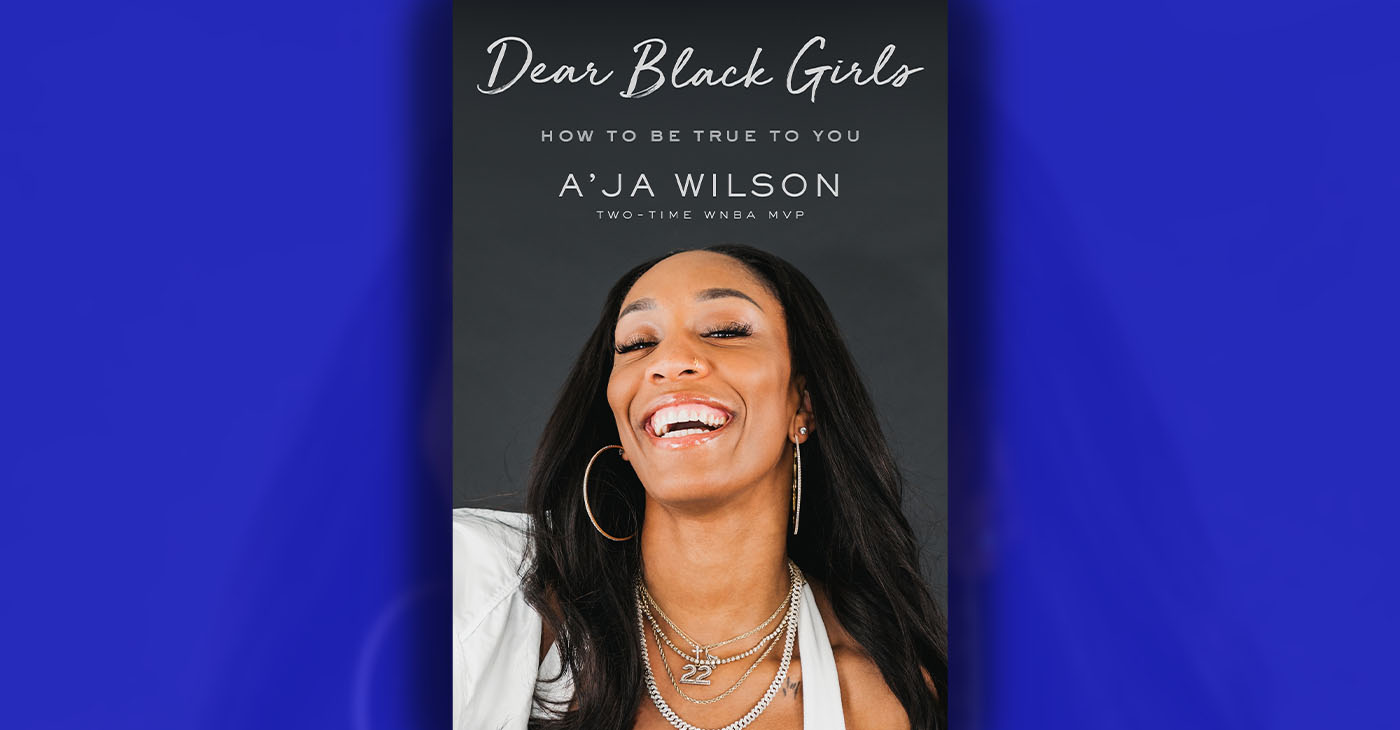

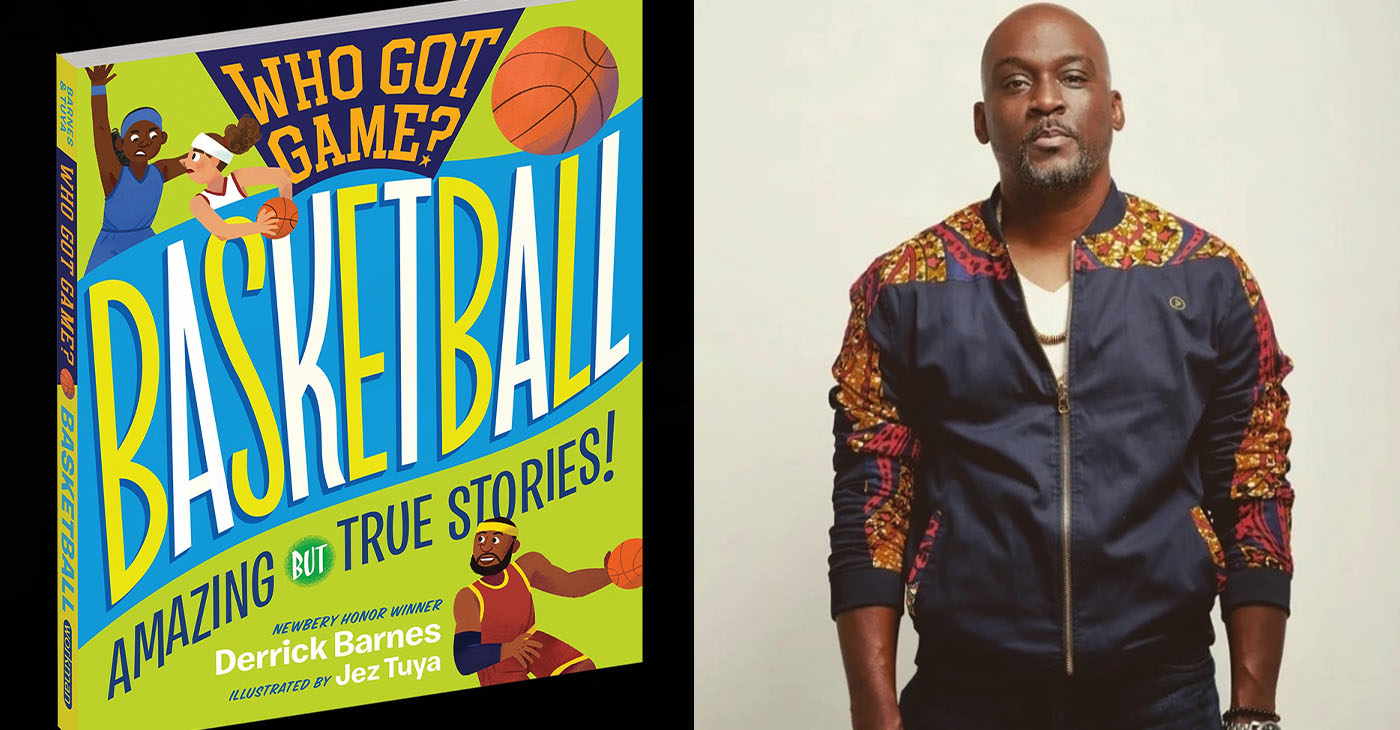

Book Review: “Who Got Game? Basketball”

A little less than two feet. That’s how far you can get your two feet off the floor if you’re an average kid doing an average vertical jump. Not quite twenty-four inches, but don’t worry: the taller you grow, the higher you could be able to jump. Practice some, dribble a little, shoot more three-pointers, and you might jump right into a book like “Who Got Game? Basketball” by Derrick Barnes, illustrated by Jez Tuya.

A little less than two feet.

That’s how far you can get your two feet off the floor if you’re an average kid doing an average vertical jump. Not quite twenty-four inches, but don’t worry: the taller you grow, the higher you could be able to jump. Practice some, dribble a little, shoot more three-pointers, and you might jump right into a book like “Who Got Game? Basketball” by Derrick Barnes, illustrated by Jez Tuya.

Here we are, football season’s almost over, and your mind has turned to other things – namely, hoops set high over your head, and a round bouncy basketball. Kids like you who “got game” have had it for more than a century. Yes, the game of basketball was created by Dr. James Naismith in 1891 in Massachusetts.

In the years since, basketball has changed a lot, thanks to what Derrick Barnes calls “pioneers.” Julius “Dr. J” Erving improved the dunk. Before that, in 1950, the NBA first allowed Black basketball players on the teams. There have been super-tall players (Manute Bol and Gheorghe Muregan were both seven feet, seven tall) and smaller b-ballers – five-three Muggsy Bogues had a vertical jump of nearly four feet! – and just two years after the game was invented, America had its first women’s team.

A lot of off-court people poured themselves into the game, too. Barnes writes, for example, about Pat Summitt, hoopster, leader, and “one of the greatest coaches in all of sports history.” Her record of 1,098 wins ranks her at first-place in coaching women’s basketball, and as the coach with the second-most wins overall.

You can probably guess that in a book about buckets, there are bucketfuls of stats. Barnes includes a list of NBA players who jumped to a team right out of high school. He writes about the greatest basketball park ever, he explains why winners cut down the net, how Title IX changed the game, why backboards rarely break into a zillion pieces anymore, high scores, bad injuries, “hoops movies,” and where in the world you can pick up a game today.

So, your 9-to-13-year-old loves basketball so much that they dribble a ball in their sleep? They think their favorite jersey is church wear? Then you’ll be the hero of the day when you bring home “Who Got Game? Basketball.”

But first, there’s one big thing you need to know: this is not a how-to book. There aren’t any instructions inside here, no rules or plays to follow. Instead, author Derrick Barnes makes young b-ballers happy by sharing little-known info about the game they love so much, short lists, great stories about great players, wins and losses, and phrases they should know to talk the talk. All this knowledge is supported by colorful illustrations by Jez Tuya that kids will enjoy alongside the facts.

This book is for die-hard young b-ballers, but don’t be surprised if an adult finds a thing or two to learn here. “Who Got Game? Basketball” is a book any fan will want to jump on.

“Who Got Game? Basketball” by Derrick Barnes, Illustrated by Jez Tuya, c.2023, Workman Publishing, $16.99, 172 pages.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoAG Bonta Says Oakland School Leaders Should Comply with State Laws to Avoid ‘Disparate Harm’ When Closing or Merging Schools

-

Community7 days ago

Community7 days agoOakland WNBA Player to be Inducted Into Hall of Fame