Activism

It Takes a Community: Oakland Group Puts People First in Domestic Violence Fight

Located in Oakland, the Family Violence Law Center (FVLC) served 2,673 survivors and provided legal support to 1,186 survivors across Alameda County during its last fiscal year, July 2019-June 2020.

Firmly believing that those closest to the problem are also closest to the solution, Carolyn Russell, executive director of A Safe Place homeless shelter in Oakland, says she was guided to an idea that she is confident will contribute to addressing domestic violence in her city: a community-led coalition.

Inspired by faith-based leaders, community members, business owners, violence survivors and, significantly third- and fourth- generation Oaklanders, Russell set out to re-establish the charge of a subgroup within the Oakland Violence Prevention Coalition.

“All of the statistics – the calls we get on our hotline, the number of requests for restraining orders – are proof beyond measure that the City of Oakland should be creating a coalition,” Russell said.

Domestic violence statistics in Oakland are startling and alarming, she says.

Located in Oakland, the Family Violence Law Center (FVLC) served 2,673 survivors and provided legal support to 1,186 survivors across Alameda County during its last fiscal year, July 2019-June 2020. This year has shown further increases in incidents as well as a significant upswing in the severity of violence reported by survivors.

“During the month of June alone, we received 76 new requests for emergency civil legal assistance from survivors and in all of May, we received only 35 new requests. So, we are definitely seeing a surge in level of need as things reopen,” said Marissa Seko, an intervention unit manager for FVLC.

At the behest of the community, the City of Oakland formed a Department of Violence Prevention (DVP) in 2017.

While are a number of non-profit advocates and organizations that address domestic violence, Russell felt a particular voice was missing – those who are directly impacted by the violence.

She was inspired by other Bay Area cities like San Francisco and Berkeley where community coalitions are working to address domestic violence.

So, she is utilizing her resources to start the new Domestic Violence Coalition for Oakland (DVCO) dedicated to serving as an advocacy group. Their work is centered on the voices of members of the community.

They are meeting monthly via Zoom since early 2021, discussing the intersection of gun violence, community violence and domestic violence.

“We talk about it all, because as one member said, ‘pain is pain,’” Russell said.

When she first started working at A Safe Place as director in the 1970s, Russell observed that what could be characterized as the ‘sledgehammer’ approach wasn’t working for Black people. She was referring to the custom of criminalizing perpetrators and primarily relying on law enforcement, the criminal justice system and social service agencies to resolve domestic violence and disputes.

Shel was surprised to learn that most of the victims she encountered did not want to press criminal charges against their abusers and certainly didn’t want them incarcerated.

And, critically, the women didn’t want to leave their children behind.

As she made her journey from director to executive director of A Safe Place, Russell began to incorporate the desires of the survivors into the culture of the shelter. (At that time, boys over 12 years old weren’t allowed to stay at the shelter, a policy she eventually reversed.)

The coalition is also different from other organizations serving survivors it has no obligations to a funder, which means they can do whatever they want.

“No one is telling us what our goals and objectives should be,” Russell said.

Antoine Towers, who co-chairs the coalition with Russell, is a veteran of this community approach. The two of them were part of the advocacy that led to the City of Oakland creating and funding DVP.

Raised by women who were abused by men, as a teenager Towers assaulted one of those abusers. But he found that satisfaction was fleeting.

Once he was an adult himself and had experienced his own problems in relationships, Towers explained, he gained insight into some of the contributing factors to intimate violence in families and how the harm ripples out into the community and is passed from generation to generation.

“There are so many components that lead to abuse in all aspects,” he said. There is a tendency, he says, to look at harm narrowly, but “All triggers are important.”

Towers, who is a barber, coaxes customers and bystanders into conversations that help them illuminate their own circumstances and experiences with domestic violence. One theme he noticed was how misunderstanding escalates to disagreement and sometimes to what he calls “the point of no return,” referring to domestic violence.

Intimate one-on-one conversations like the ones Towers has with his clients is an approach the coalition also uses.

“We need to learn proper ways of hearing each other,” Towers said, observing that the Black community has “a bunch of people who lost a lot of people over the years.”

“How do we get ourselves heard? How do we learn what we really want and then get the resources to support it?” He asked.

DVCO is deliberately widening its focus to include men and boys. Historically, domestic violence service providers like A Safe Place have focused on intimate partner abuse mainly involving women. DVCO recognizes that there are all kinds of family violence that don’t get voiced.

“My issue with my (service provider) partners is that they only serve women and girls,” Russell said. “They don’t focus on men.”

The prospect of bringing men and boys to the center of the conversation is one of the things that DVCO member Rev. Harold Mayberry finds exciting.

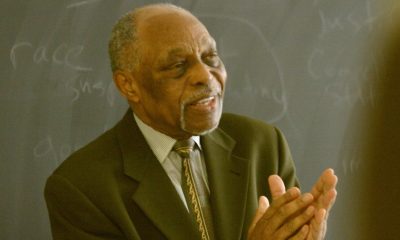

Now presiding elder of the Oakland/San Joaquin region of the African Methodist Episcopal Church Fifth District, Mayberry spent 48 years as pastor of First A.M.E Church in Oakland where, from the pulpit, he encouraged people who had survived abuse to seek help. He also counseled them in private.

Although he knew some who had suffered domestic violence, no men ever came forward, he said. He wants the new coalition to change that.

“We’ve got to reach people who would not normally come forward,” Mayberry said. “Carolyn wants to include men who are the concealed victims of domestic violence because we are taught to be macho and not show pain.”

DVCO member Patanisha Ali heard a lot of painful accounts when she was helping to document the impact of violence on Oakland citizens in the prelude to the formation of Oakland’s DVP. That experience taught her that people in the community are often unaware of civic and non-profit organizations that are supposed to provide relief – and how their voices may influence policy.

“What is missing is an authentic relationship with the people impacted,” she said. “Those impacted don’t get involved in politics, but they need to. How do we make that happen?”

While several organizations – including A Safe Place – hold workshops for young people on preventing domestic violence, DVCO intends to get more young people involved.

To that end, and at this point in its development, DVCO will use social media as a primary tool to educate the community.

But DVCO members will not be the only ones providing that education. There is wisdom in the experience of the community that is essential and useful. “We know there are people who were assaulted when they were children,” Russell said. “In their survival, they learned valuable lessons to heal themselves that can be shared.”

Ali observes that although there is a lot of current brokenness and historic pain in the Black community, there is still hope. “Another aspect is that people coming to (DVCO’s) table are healers and creatives and survivors,” she said.

Towers is looking forward to creating spaces to document the wisdom in community dialogue. He recounts getting his neighbor to a place of liberation from the cycle of misunderstanding and a sense of woundedness he felt when interacting with his spouse.

“It’s not wrong what she said,” Towers advised the man. “You are not hearing what she needs you to understand.”

With mediation, he said, we may begin to respect each other more. “I think moments like that are needed in our community,” Towers said. “We all grow up in it, but we don’t want to keep those same outcomes.”

“We don’t want to do the ‘same ol’ same ol,’” Russell said.

“We are excited to bring the voices of the ‘hood to the table,” said Ali, who is hoping that with those voices the community can experience a shift.

“Peace can happen here,” she added.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Schools Honor Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice. His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

By Post Staff

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice.

His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

One OUSD school is named in his honor: Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy (KDA) elementary in East Oakland.

Several years ago, founding KDA Principal Charles Wilson, in a video interview with anti-hate organization “Not In Our Town,” said, “We chose the name Fred Korematsu because we really felt like the attributes that he showed in his work are things that the children need to learn … that common people can stand up and make differences in a large number of people’s lives.”

Fred Korematsu was born in Oakland on Jan. 30, 1919. His parents ran a floral nursery business, and his upbringing in Oakland shaped his worldview. His belief in the importance of standing up for your rights and the rights of others, regardless of race or background, was the foundation for his activism against racial prejudice and for the rights of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the start of the war, Korematsu was turned away from enlisting in the National Guard and the Coast Guard because of his race. He trained as a welder, working at the docks in Oakland, but was fired after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Fear and prejudice led to federal Executive Order 9066, which forced more than 120,000 Japanese Americans out of their homes and neighborhoods and into remote internment camps.

The 23-year-old Korematsu resisted the order. He underwent cosmetic surgery and assumed a false identity, choosing freedom over unjust imprisonment. His later arrest and conviction sparked a legal battle that would challenge the foundation of civil liberties in America.

Korematsu’s fight culminated in the Supreme Court’s initial ruling against him in 1944. He spent years in a Utah internment camp with his family, followed by time living in Salt Lake City where he was dogged by racism.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford overturned Executive Order 9066. Seven years later, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco vacated Korematsu’s conviction. He said in court, “I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong and do something about it so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color.”

Korematsu’s dedication and determination established him as a national icon of civil rights and social justice. He advocated for justice with Rosa Parks. In 1998, President Bill Clinton gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom saying, “In the long history of our country’s constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls … To that distinguished list, today we add the name of Fred Korematsu.”

After Sept. 11, 2001, Korematsu spoke out against hatred and discrimination, saying what happened to Japanese Americans should not happen to people of Middle Eastern descent.

Korematsu’s roots in Oakland and his education in OUSD are a source of great pride for the city, according to the school district. His most famous quote, which is on the Korematsu elementary school mural, is as relevant now as ever, “If you have the feeling that something is wrong, don’t be afraid to speak up.”

Activism

WOMEN IMPACTING THE CHURCH AND COMMUNITY

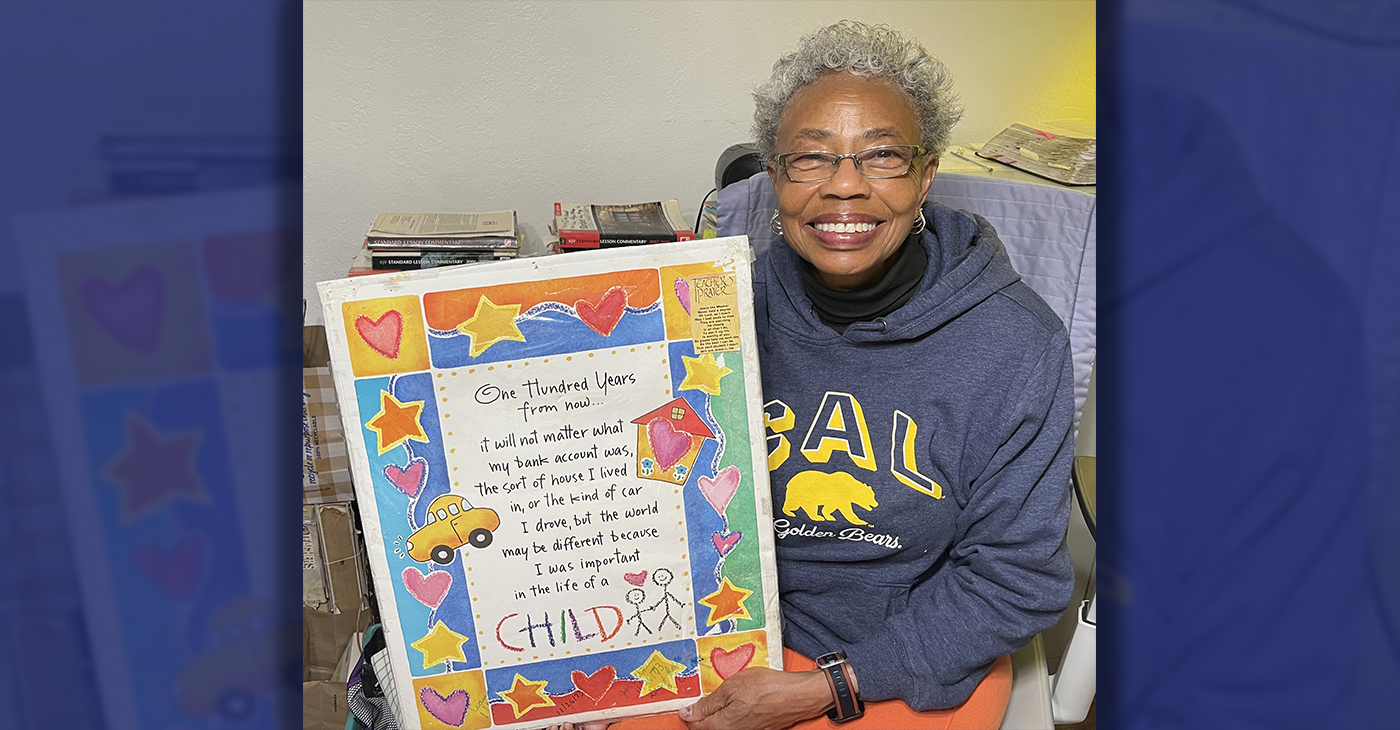

Juanita Matthews, better known as “Sister Teacher,” is a walking Bible scholar. She moved to California from the great state of Arkansas in 1971. Sister Teacher has a passion for teaching. She has been a member of Bible Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church since 1971.

Sister Juanita Matthews

55 Years with Oakland Public School District

The Teacher, Mother, Community Outreach Champion, And Child of God

Juanita Matthews, better known as “Sister Teacher,” is a walking Bible scholar. She moved to California from the great state of Arkansas in 1971. Sister Teacher has a passion for teaching. She has been a member of Bible Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church since 1971. She followed her passion for teaching, and in 1977 became the lead teacher for Adult Class #6. Her motto still today is “Once My Student, Always My Student”.

Beyond her remarkable love for the Lord, Sister Teacher has showcased her love for teaching by working for the Oakland Unified School District for 55 years, all but four of those years spent at Emerson Elementary and Child Development School. She truly cares about her students, making sure they have the tools/supplies needed to learn either at OUSD or Bible Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church.

She’s also had a “Clothes Closet Ministry” for 51 years, making sure her students have sufficient clothing for school. The Clothes Closet Ministry extends past her students, she has been clothing the community for over 50 years as well. She loves the Lord and is a servant on a mission. She is a loving mother to two beautiful children, Sandra and Andre. This is the impact this woman of God has on her church and the community.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 20 – 26, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: Lady Day and The Lights!

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoFrom Raids to Revelations: The Dark Turn in Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs’ Saga

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoBaltimore Key Bridge Catastrophe: A City’s Heartbreak and a Nation’s Alarm

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoBaltimore’s Key Bridge Struck by Ship, Collapses into Water

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024