Education

How Daagye Hendricks Serves Community, City Schools and UAB

Daagye Hendricks is not one to remain stationary. The Birmingham Board of Education member, businesswoman and mom of a 16-year-old, had an opportunity to become a part of the Living Donor Navigator Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB)—and she didn’t hesitate to join.THE BIRMINGHAM TIMES —

By Ameera Steward

Daagye Hendricks is not one to remain stationary. The Birmingham Board of Education member, businesswoman and mom of a 16-year-old, had an opportunity to become a part of the Living Donor Navigator Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB)—and she didn’t hesitate to join.

Hendricks wanted to not only try something different but also do something she believes in: “Diversify yourself, stay fresh, and make sure you sharpen your toolbox and your skill set.”

“The opportunity to create a [Living Donor Navigator] program or be a part of that was, of course, exciting. More importantly, … I knew I could make a difference, and that is gratifying,” she said.

More than 110,000 people in the United States are on waiting lists to receive life saving organs, and nearly 100,000 of those are awaiting a kidney. The Living Donor Navigator Program, founded in 2017, works with both recipients and donors to identify needs and guide each through the process, from transplantation to post-transplant. Hendricks is one of two patient navigators in the program.

“This body of work has never existed,” she said. “It is evolving every day as we continuously improve our standards driven by our patient outcomes.”

The initial goal was to have two transplants from the first set of classes in the first year—they ended up with more than 20.

Outreach

Because of the program’s importance, Hendricks often works weekends: “On a Saturday, even.”

“I sometimes hate losing that time away from my family, but it is always a joy to be able to help someone along the way. The benefits we have been able to receive since this program started are very gratifying, to be able to reduce somebody’s wait time for a kidney transplant to six months to a year from four to 10 years is huge,” said Hendricks.

Her duties include educational outreach, letting people know how easy it is to donate a kidney and talking about the needs for kidney donation. She also works with people who have signed up for her class and helps them navigate the process of identifying and attracting live donors. The class is designed primarily for family members of the patient, she said.

“It is hard enough to go through dialysis and fight the emotional struggles that go along with that to stay healthy enough to get transplanted,” Hendricks said. “Our goal is to teach the family members—the wife, the husband, the coworker, the church member—how to stand up and be an advocate for the other person’s care. Let us help them stay healthy enough to get transplanted. Let me teach you how to do the outreach to help save your friend or your family member’s life.”

Learning the Business

Public service is part of Hendricks’s DNA.

“That is inherently who I am,” she said. “The best part of me and my day is public service. I want to help someone else. I want to make a difference. I want to be impactful. I want to make someone else’s day or way easier for them. That is gratifying. That is why I serve.”

Hendricks, 44, learned to help others growing up with her family in Birmingham. She watched her grandfather run his restaurant, Bud’s Deli, on Finley Boulevard in North Birmingham’s Acipco neighborhood. Her grandfather’s brothers and sisters owned the Hendricks Brothers restaurant on the same block. One of her grandmothers owned a beauty shop and her other grandmother helped operate the deli business. Her parents, Elias and Gaynell Hendricks, own the Wee Care Academy day care center.

“I really didn’t know anything different,” said Hendricks. “When I was a little girl, my grandfather owned a delicatessen. … When I was about 4 or 5, I learned how to count money because he had me working his cash register. I was enthralled by that process of actually counting money and … the process of selling those goods—sandwiches, hot dogs, sodas. … That’s what really attracted me to doing business.”

Hendricks, currently in her second term as a board member, attended pre-kindergarten through fourth grade in New Jersey at Oak Knoll, a Montessori school. When the family moved to Birmingham, she went to Cherokee Bend and St. Paul’s elementary schools. She attended Altamont School from sixth through ninth grades and Homewood High School in her sophomore year, and she graduated from Shades Valley High School.

“I went to three different high schools, and that’s part of the reason why I got on the [Birmingham] School Board,” she said. “I have a very diverse academic background, and I wish I could see those types of advancements happen in public education, as well.”

After high school, Hendricks enrolled at Clark Atlanta University, thinking she was going to major in marketing, but she really wanted to be a social worker. Eventually, she changed her major to finance.

“I come from a family of entrepreneurs,” she said.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in finance, Hendricks later attended the University of Alabama to obtain an Executive Master of Business Administration degree; she has one more class to finish before graduating.

Around 2001, she moved to the Norwood community and embarked on another chapter in her life of service when she joined other residents to generate buzz, to create “… excitement about Norwood and get people interested in wanting to relocate … [to the neighborhood],” she said.

Norwood had two schools, Norwood Elementary School and Kirby Middle School, and both closed: “We realized over the years the impact that made in the neighborhood,” she said.

Hendricks worked to reopen one of those schools, and that gave her insight about the needs of her community.

“I was able to go into the [school board] position knowing some of the critical needs of my district,” she said.

Elected to School Board

In 2013, Hendricks was elected to the Birmingham Board of Education representing District 4; she was re-elected in 2017.

“The state took over the leadership [of the school system], and that’s what motivated me to run. … I really wanted to make a difference right where I am for my child and for all the students,” said Hendricks, whose son is a student at Ramsay High School and was attending Phillips Academy when she decided run for the school board.

Hendricks said Birmingham City Schools are headed in the right direction and have their finances in better order than when she first joined the board. Her district has five schools—Hayes K-8, Hudson K-8, Inglenook School, Norwood Elementary School, and Woodlawn High School—that serve 19 neighborhoods.

“Not only are the students within those schools my customers, but the neighborhood, the parents, the community are, too,” she said, explaining that board members don’t get assistants, so she has to answer each phone call.

“There’s an expectation to be available and accessible to the community. That is critical and necessary.”

“Board members have the responsibility of not only hiring, firing, and governing the superintendent but also being public servants in our communities and being stakeholders with our parents and our corporate partners.”

Mentoring

In addition to serving on the school board, Hendricks serves as a mentor—something she began long before being elected. She meets many of her students while they are in high school and stays with them through college.

“That’s just a part of me because I know the struggles academically,” Hendricks said. “I was not the smartest student in class. I had to work hard. I had to struggle sometimes. When I see my students … transitioning into that position, I do anything I can to help.”

Hendricks’s style of help includes scholarships, subsidies, “and just being there.”

“[When they say], ‘Hey, look, it’s getting hard out here, I don’t know if I’m going to make it through next semester.’ [I’m there] being that support, saying, ‘Hey, you can keep doing it,’ or aligning resources.”

Opportunity to Succeed

Oftentimes, Hendricks believes, the only thing separating children in terms of success is the opportunity to succeed.

“If you can bridge resources, oftentimes our children will reach up and grab them,” she said. “They just don’t know where to go. … I like to connect those dots, so we can make these things easier and work together to transform the community.”

Hendricks’s love of working with students began at her family’s Wee Care Academy, where she served as vice president of operations from 1999 to 2005 before taking a position at Birmingham-Shuttlesworth Airport; she returned to the day care from 2013 to 2017.

“Working with children keeps you energized,” she said. “It makes you keep changing your perspective. It makes you broaden your opinions. Our students, our children are the future. If you want to know where you’re going, you need to talk to the folks that are going there with you. I think we often ignore or overlook the words of children. I interact better with children.”

Hendricks has worked with Wee Care in different capacities since her college years.

“That made me not only realize how important it is to listen to children … but also realize the importance of service … [and] education,” she said. “Our children who graduated through Wee Care in the past 30 years … probably have almost 98 or 99 percent college-[attendance] rate. … Seeing that in [our] business, I feel compelled to try to translate that into public education.”

This article originally appeared in The Birmingham Times.

Activism

WOMEN IMPACTING THE CHURCH AND COMMUNITY

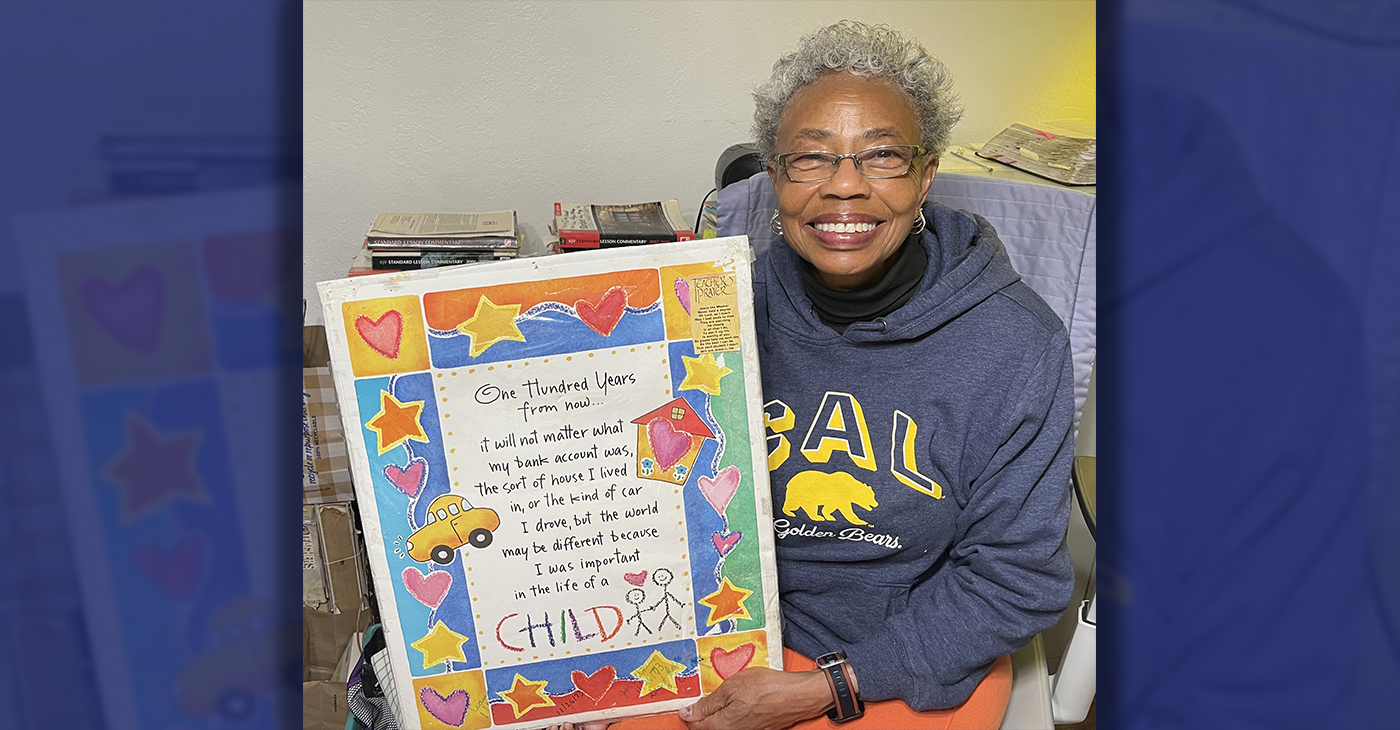

Juanita Matthews, better known as “Sister Teacher,” is a walking Bible scholar. She moved to California from the great state of Arkansas in 1971. Sister Teacher has a passion for teaching. She has been a member of Bible Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church since 1971.

Sister Juanita Matthews

55 Years with Oakland Public School District

The Teacher, Mother, Community Outreach Champion, And Child of God

Juanita Matthews, better known as “Sister Teacher,” is a walking Bible scholar. She moved to California from the great state of Arkansas in 1971. Sister Teacher has a passion for teaching. She has been a member of Bible Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church since 1971. She followed her passion for teaching, and in 1977 became the lead teacher for Adult Class #6. Her motto still today is “Once My Student, Always My Student”.

Beyond her remarkable love for the Lord, Sister Teacher has showcased her love for teaching by working for the Oakland Unified School District for 55 years, all but four of those years spent at Emerson Elementary and Child Development School. She truly cares about her students, making sure they have the tools/supplies needed to learn either at OUSD or Bible Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church.

She’s also had a “Clothes Closet Ministry” for 51 years, making sure her students have sufficient clothing for school. The Clothes Closet Ministry extends past her students, she has been clothing the community for over 50 years as well. She loves the Lord and is a servant on a mission. She is a loving mother to two beautiful children, Sandra and Andre. This is the impact this woman of God has on her church and the community.

Bay Area

Rich Lyons, Longtime Campus Business, Innovation Leader, Will Be UC Berkeley’s Next Chancellor

Rich Lyons, an established economist, former dean of the Haas School of Business and the campus’s current leader for innovation and entrepreneurship, will become the next chancellor at the University of California, Berkeley, the UC Board of Regents announced on April 10.

By Jason Pohl

Rich Lyons, an established economist, former dean of the Haas School of Business and the campus’s current leader for innovation and entrepreneurship, will become the next chancellor at the University of California, Berkeley, the UC Board of Regents announced on April 10.

The board’s unanimous confirmation makes Lyons, 63, the first UC Berkeley undergraduate alumnus since 1930 to become the campus’s top leader. In an interview this week, Lyons said he credits his Berkeley roots and his campus mentors with encouraging him to ask big questions, advance institutional culture and enhance public education — all priorities of his for the years to come.

Lyons, who will be Berkeley’s 12th chancellor, will succeed Chancellor Carol Christ, who announced last year that she’d step down as chancellor on July 1.

“I am both thrilled and reassured by this excellent choice. In so many ways, Rich embodies Berkeley’s very best attributes, and his dedication to the university’s public mission and values could not be stronger,” Christ said. “I am confident he will bring to the office visionary aspirations for Berkeley’s future that are informed by, and deeply respectful of, our past.”

Rising through the Berkeley ranks

Born in 1961, Lyons grew up in Los Altos in the early days of the Silicon Valley start-up boom.

He attended Berkeley, where he graduated in 1982 with a Bachelor of Science degree in business and finance. Lyons went on to earn his Ph.D. in 1987 in economics from MIT. After six years teaching at Columbia Business School, Lyons returned west, where in 1993 he joined the Berkeley faculty as a professor of economics and finance, specializing in the study of international finance and global exchange rates.

He’s remained on campus since, with one notable exception.

Starting in 2006, Lyons spent two years working at Goldman Sachs as the chief learning officer. It was a period that instilled in him an appreciation for leadership and the importance of organizational culture.

He carried those lessons with him when he returned to campus in 2008 and became the dean of the Haas School of Business.

While dean, Lyons oversaw the construction of Connie & Kevin Chou Hall, a state-of-the-art academic building that opened in 2017 and is celebrated for its sustainability. He also helped establish two new degree programs, linking the business school with both the College of Engineering and the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology.

But it was his creation of four distinct defining leadership principles that spurred a sweeping culture initiative at the school that stands out in the minds of many. Those values — question the status quo, confidence without attitude, students always, and beyond yourself — became a creed of sorts for new students and alumni alike.

Those values are important, Lyons said, because they shape and support the cohesive structure of a strong, connected community — spanning science and technology to the arts and humanities. They also convey the story about what it means to be at Berkeley and to believe in the university’s public mission.

“When we are great as educators, it’s identity-making,” Lyons said. “We’re helping students and others see identities in themselves that they couldn’t see.”

Lyons in January 2020 became Berkeley’s first-ever chief officer of innovation and entrepreneurship.

Building on his research exploring how leaders drive innovation and set behavioral norms and culture, Lyons worked to expand and champion Berkeley’s rich portfolio of innovation and entrepreneurship activities for the benefit of students, faculty, staff, startups and external partners.

It was a major commitment to thinking outside the box, he said. One need only look to the Berkeley Changemaker program that he helped launch in 2020 to see innovation and entrepreneurship in action.

The campuswide program with some 30 courses tells the story of what Berkeley is — the story that members of the Berkeley community can tell long into the future. Berkeley Changemaker started as an idea and its courses quickly became among the most popular academic offerings on campus.

“Over 500 students showed up,” he said. “Why? Because it’s a narrative. It’s not just a name. It’s not just a curriculum. It’s not just a course. It’s a way of living, and it’s a way of living that Berkeley has occupied forever. This idea that there’s got to be a better way to do this, question the status quo.”

Community

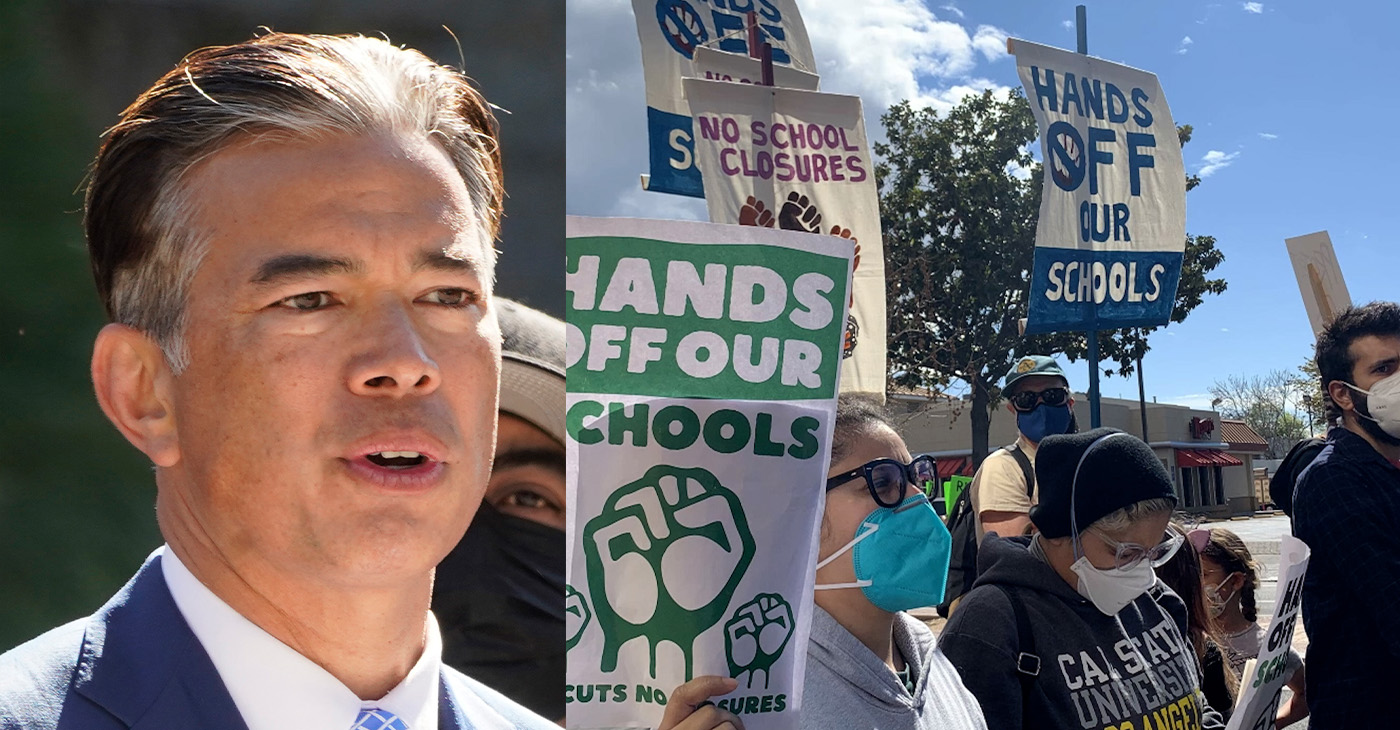

AG Bonta Says Oakland School Leaders Should Comply with State Laws to Avoid ‘Disparate Harm’ When Closing or Merging Schools

California Attorney General Rob Bonta sent a letter this week to the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) Board of Education saying the district has a duty to comply with state education and civil rights laws to protect students and families from “disparate harm,” such as segregation and discrimination, if the district goes ahead with school closures, mergers or consolidations in 2025-2026.

AG Bonta said DOJ investigation of 2022 closure decisions would have negatively impacted Black and low-income families.

By Post Staff

California Attorney General Rob Bonta sent a letter this week to the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) Board of Education saying the district has a duty to comply with state education and civil rights laws to protect students and families from “disparate harm,” such as segregation and discrimination, if the district goes ahead with school closures, mergers or consolidations in 2025-2026.

The letter and an accompanying media release announced the findings of the California Department of Justice’s (DOJ) investigation into the OUSD Board’s Feb. 8, 2022, decision to close Parker Elementary, Brookfield Elementary, Carl B. Munck Elementary, Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy, Grass Valley Elementary, Horace Mann Elementary, and Community Day School and eliminate grades 6-8 of Hillcrest Elementary and La Escuelita Elementary.

“All school districts and their leadership have a legal obligation to protect vulnerable children and their communities from disparate harm when making school closure decisions,” said Attorney General Bonta.

“The bottom line is that discrimination in any form will not be tolerated,” he said. “I am committed to working with OUSD’s leadership to achieve successful outcomes for students.

“My office will continue to monitor OUSD’s processes and decision-making as it moves forward with the required community engagement, equity impact analysis, and planning to implement any future closures, mergers, or consolidations” to ensure compliance with California’s Constitution, AB 1912, and anti-discrimination laws.

By press time, the school district did not respond to a request for comment from OUSD.

The DOJ’s findings showed that the February 2022 decision, later partially rescinded, would have disproportionately impacted Black and low-income elementary students, as well as high-need students with disabilities, according to the media release.

The Attorney General outlined concerns about criteria OUSD has announced that it may rely on to determine future closures, mergers, and consolidations and provided recommendations to ensure OUSD does not violate state law, including prohibitions against closure decisions that reinforce school segregation or disproportionately impact any student group as required by the State Constitution, AB 1912, and anti-discrimination laws.

According to AB 1912, passed in September 2022, financially distressed school districts contemplating school closures, mergers, or consolidations must engage the community before closing schools; conduct an equity impact assessment; and provide the public with the set of criteria the district plans to utilize to make decisions.

In the letter, DOJ identified a “problematic” approach to planning for closing schools in 2025-2026 and “strongly recommends” steps OUSD should take going forward.

- “Take affirmative steps to ensure that its enrollment and attendance boundary and school closure decisions alleviate school segregation and do not create disproportionate transportation burdens for protected subgroups.”

- Don’t solely utilize criteria such as school facilities’ conditions, school operating costs, and school capacity without also including an assessment of past and present inequities in resources “due to educational segregation or other causes.”

- Some of OUSD’s proposed guidelines “may improperly penalize schools serving students with disabilities and students who have high needs.”

- The district’s decisions should also include “environmental factors, student demographics and feeder attendance patterns, transportation needs, and special programs.”

- Avoid overreliance on test scores and other quantitative data without also looking at “how each school is serving the needs of its specific student body, especially as it relates to historically marginalized communities.”

- “Engage an independent expert to facilitate community input and equity impact.”

The letter also emphasized that DOJ is willing to provide “feedback and consultation at any time during the process to ensure that OUSD’s process and outcomes are legally compliant and serve the best interests of the school community and all of its students.”

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 20 – 26, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: Lady Day and The Lights!

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoFrom Raids to Revelations: The Dark Turn in Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs’ Saga

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoBaltimore Key Bridge Catastrophe: A City’s Heartbreak and a Nation’s Alarm

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoBaltimore’s Key Bridge Struck by Ship, Collapses into Water

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

1 Comment