Black History

‘Clotilda,’ the last known slave ship to arrive in the U.S., is found

SOUTH FLORIDA TIMES — Last year, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Slave Wrecks Project (SWP) joined the effort to help involve the community of Africatown in the preservation of the history, explains Smithsonian curator and SWP co-director Paul Gardullo.

By Allison Keyes

One hundred and fifty-nine years ago, MOBILE, Ala. – Once slave traders stole Lorna Gail Woods’ great great grandfather from what is now Benin in West Africa.

Her ancestor, Charlie Lewis, was brutally ripped from his homeland, along with 109 other Africans, and brought to Alabama on the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to arrive in the United States. Today, elusive for decades, have been found along the Mobile River, near 12 Mile Island and just north of the Mobile Bay delta.

“The excitement and joy is researchers confirmed that the remains of that vessel, long rumored to exist but overwhelming,”says Woods, in a voice trembling with emotion. She is 70 years old now. But she’s been hearing stories about her family history and the ship that tore them from their homeland since she was a child in Africatown, a small community just north of Mobile founded by the Clotilda’s survivors after the Civil War.

The authentication and confirmation of the Clotilda was led by the Alabama Historical Commission and SEARCH Inc., a group of maritime archaeologists and divers who specialize in historic shipwrecks.

Last year, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Slave Wrecks Project (SWP) joined the effort to help involve the community of Africatown in the preservation of the history, explains Smithsonian curator and SWP co-director Paul Gardullo.

Two years ago, Gardullo says talks began about mounting a search for the Clotilda based on conversations with the descendants of the founders of Africatown. Then last year, it seemed that Ben Raines, a reporter with AL.com had found the Clotilda, but that wreck turned out to be too large to be the missing ship. Gardullo says everyone involved got moving on several fronts to deal with a complicated archaeological search process to find the real Clotilda.

“This was a search not only for a ship. This was a search to find our history and this was a search for identity, and this was a search for justice,” Gardullo explains. “This is a way of restoring truth to a story that is too often papered over. Africatown is a community that is economically blighted and there are reasons for that. Justice can involve recognition. Justice can involve things like hard, truthful talk about repair and reconciliation.”

Even though the U.S. banned the importation of the enslaved from Africa in 1808, the high demand for slave labor from the booming cotton trade encouraged Alabama plantation owners like Timothy Meaher to risk illegal slave runs to Africa.

Meaher took that risk on a bet that he could bring a shipload of Africans back across the ocean. In 1860, his schooner sailed from Mobile to what was then the Kingdom of Dahomey under Captain William Foster. He bought Africans captured by warring tribes back to Alabama, skulking into Mobile Bay under the cover of night, then up the Mobile River. Some of the transported enslaved were divided between Foster and the Meahers, and others were sold. Foster then ordered the Clotilda taken upstream, burned and sunk to conceal the evidence of their illegal activity.

After being freed by Union soldiers in 1865, the Clotilda’s survivors sought to return to Africa, but they didn’t have enough money. They pooled wages they earned from selling vegetables and working in fields and mills to purchase land from the Meaher family. Calling their new settlement Africatown, they formed a society rooted in their beloved homeland, complete with a chief, a system of laws, churches and a school. Woods is among the descendants who still live there. Finally, she says, the stories of their ancestors were proved true and now have been vindicated.

“So many people along the way didn’t think that happened because we didn’t have proof. By this ship being found we have the proof that we need to say this is the ship that they were on and their spirits are in this ship,” Woods says proudly. “No matter what you take away from us now, this is proof for the people who lived and died and didn’t know it would ever be found.”

The museum’s founding director, Lonnie Bunch, says the discovery of The Clotilda tells a unique story about how pervasive the slave trade was even into the dawn of the Civil War.

“One of the things that’s so powerful about this is by showing that the slave trade went later than most people think, it talks about how central slavery was to America’s economic growth and also to America’s identity,” Bunch says. “For me, this is a positive because it puts a human face on one of the most important aspects of African American and American history. The fact that you have those descendants in that town who can tell stories and share memories – suddenly it is real.”

Curators and researchers have been in conversation with the descendants of the Clotilda survivors to make sure that the scientific authentication of the ship also involved community engagement.

Smithsonian curator Mary Elliott spent time in Africatown visiting with churches and young members of the community and says the legacy of slavery and racism has made a tangible footprint here in this place across a bridge from downtown Mobile. In a neighborhood called Lewis Quarters, Elliott says what used to be a spacious residential neighborhood near a creek is now comprised of a few isolated homes encroached upon by a highway and various industries.

“What’s powerful about Africatown is the history. What’s powerful about it is the culture. What’s powerful about it is the heritage stewardship, that so many people have held onto this history, and tried to maintain it within the landscape as best they could,” Elliott says. “But it also shows the legacies of slavery. You see environmental racism. You see where there’s blight and not necessarily because the residents didn’t care; but due to a lack of resources, which is often the case for historic black communities across the country. When people drive through that landscape, they should have a better sense of the power of place, how to read the land and connect to the history.”

There are no photographs of the site where the Clotilda was found or of the wreck itself. “[The ship] wasn’t very deep.

Eight to ten feet at most,” Sadiki recalls. “But the conditions are sort of treacherous. Visibility was almost zero and there’s some current, but the most important thing is that you’re among wreckage that you cannot see. There’s a whole host of possibilities to being injured, from being impaled, to getting snagged and so forth.”

We call our village Affican Town. We say dat ‘cause we want to go back in de Affica soil and we see we cain go. Derefo’ we makee de Affica where dey fetch us.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Black History

Matthew Henson: Explorer Extraordinaire

Matthew Henson, a trailblazing explorer who overcame countless obstacles to leave an incredible mark on history. Born on August 8, 1866, in Charles County, Maryland, his journey is a testament to the power of determination and the spirit of adventure.

By Tamara Shiloh

Matthew Henson, a trailblazing explorer who overcame countless obstacles to leave an incredible mark on history. Born on August 8, 1866, in Charles County, Maryland, his journey is a testament to the power of determination and the spirit of adventure.

Henson’s life began amidst the backdrop of post-Civil War America, where opportunities for African Americans were scarce. From a young age, he possessed an insatiable curiosity about the world beyond his small town. At the age of 12, he embarked on a journey that would change the course of his life forever when he joined a merchant ship as a cabin boy.

His most famous expedition was his journey to the Arctic with renowned explorer Robert E. Peary. In 1887, Henson joined Peary’s crew as a seaman and quickly proved himself to be invaluable with his skills as a navigator and craftsman. Over the course of several expeditions, Matthew endured extreme cold, treacherous terrain, and grueling conditions as he and Peary sought to reach the elusive North Pole.

In 1908–09, Peary set out on his eighth attempt to reach the North Pole. It was a big expedition, with Peary planning to leave supplies along the way. When he and Henson boarded their ship, the Roosevelt, leaving Greenland on August 18, 1909, they were joined by a large group. This included 22 Inuit men, 17 Inuit women, 10 children, 246 dogs, 70 tons of whale meat, blubber from 50 walruses, hunting gear, and tons of coal.

In February, Henson and Peary left their anchored ship at Ellesmere Island’s Cape Sheridan, along with the Inuit men and 130 dogs. They worked together to set up a trail and supplies along the way to the Pole.

Peary picked Henson and four Inuit people to join him in the final push to the Pole. However, before they reached their destination, Peary couldn’t walk anymore and had to ride in a dog sled. He sent Henson ahead to scout the way. In a later interview with a newspaper, Henson recalled being in the lead and realizing they had gone too far. The group turned back, and Henson noticed his footprints helped guide them to their destination. At that location, Henson planted the American flag.

Henson’s legacy extends far beyond his expeditions to the Arctic. He shattered racial barriers in the world of exploration and inspired countless individuals, regardless of race, to dream big and pursue their passions. In 1937, he was finally recognized for his achievements when he was inducted into The Explorers Club, an organization dedicated to promoting scientific exploration and field research.

Matthew Henson died in the Bronx, New York, on March 9, 1955, at the age of 88.

Art

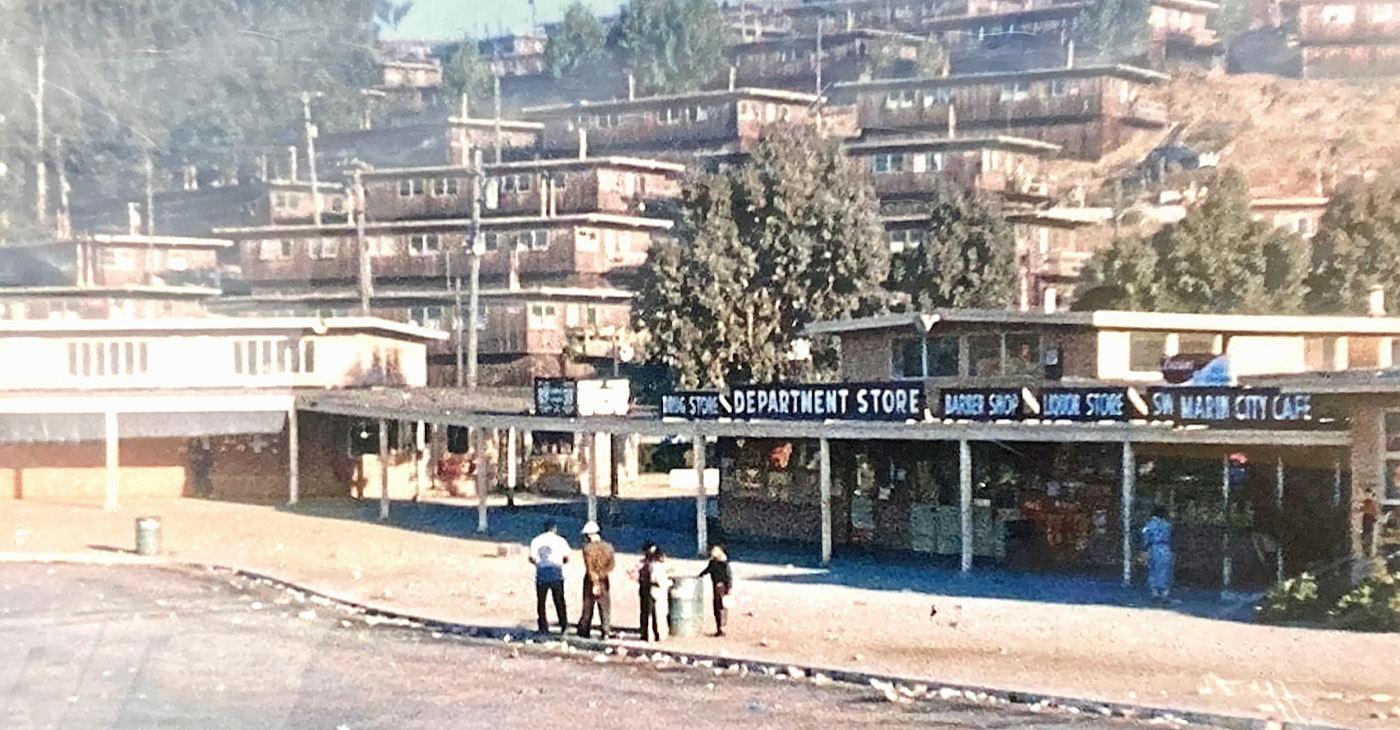

Marin County: A Snapshot of California’s Black History Is on Display

The Marin County Office of Education, located at 1111 Las Gallinas Ave in San Rafael, will host the extraordinary exhibit, “The Legacy of Marin City: A California Black History Story (1942-1960),” from Feb. 1 to May 31, 2024. The interactive, historical, and immersive exhibit featuring memorabilia from Black shipyard workers who migrated from the South to the West Coast to work at the Marinship shipyard will provide an enriching experience for students and school staff. Community organizations will also be invited to tour the exhibit.

By Post Staff

The Marin County Office of Education, located at 1111 Las Gallinas Ave in San Rafael, will host the extraordinary exhibit, “The Legacy of Marin City: A California Black History Story (1942-1960),” from Feb. 1 to May 31, 2024.

The interactive, historical, and immersive exhibit featuring memorabilia from Black shipyard workers who migrated from the South to the West Coast to work at the Marinship shipyard will provide an enriching experience for students and school staff. Community organizations will also be invited to tour the exhibit.

All will have the opportunity to visit and be guided by its curator Felecia Gaston.

The exhibit will include photographs, articles and artifacts about the Black experience in Marin City from 1942 to 1960 from the Felecia Gaston Collection, the Anne T. Kent California Room Collection, The Ruth Marion and Pirkle Jones Collection, The Bancroft Library, and the Daniel Ruark Collection.

It also features contemporary original artwork by Chuck D of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame group Public Enemy, clay sculptures by San Francisco-based artist Kaytea Petro, and art pieces made by Marin City youth in collaboration with Lynn Sondag, Associate Professor of Art at Dominican University of California.

The exhibit explores how Marin City residents endured housing inequities over the years and captures the history of plans to remove Black residents from the area after World War II. Throughout, it embodies the spirit of survival and endurance that emboldened the people who made Marin City home.

Felecia Gaston is the author of the commemorative book, ‘A Brand New Start…This is Home: The Story of World War II Marinship and the Legacy of Marin City.’ Thanks to the generous contribution of benefactors, a set of Felecia’s book will be placed in every public elementary, middle, and high school library in Marin.

In addition, educators and librarians at each school will have the opportunity to engage with Felecia in a review of best practices for utilizing the valuable primary sources within the book.

“Our goal is to provide students with the opportunity to learn from these significant and historical contributions to Marin County, California, and the United States,” said John Carroll, Marin County Superintendent of Schools.

“By engaging with Felecia’s book and then visiting the exhibit, students will be able to further connect their knowledge and gain a deeper understanding of this significant historical period,” Carroll continued.

Felecia Gaston adds, “The Marin County Office of Education’s decision to bring the Marin City Historical Traveling Exhibit and publication, ‘A Brand New Start…This is Home’ to young students is intentional and plays a substantial role in the educational world. It is imperative that our community knows the contributions of Marin City Black residents to Marin County. Our youth are best placed to lead this transformation.”

The Marin County Office of Education will host an Open House Reception of the exhibit’s debut on Feb. 1 from 4 p.m. – 6 p.m.. All school staff, educators, librarians, and community members are encouraged to attend to preview the exhibit and connect with Felecia Gaston. To contact Gaston, email MarinCityLegacy@marinschools.org

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 20 – 26, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoFrom Raids to Revelations: The Dark Turn in Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs’ Saga

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: Lady Day and The Lights!

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBaltimore Key Bridge Catastrophe: A City’s Heartbreak and a Nation’s Alarm

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBaltimore’s Key Bridge Struck by Ship, Collapses into Water