CalMatters

California High Schools are Adding Hundreds of Ethnic Studies Classes. Are Teachers Prepared?

California high school students will be required to pass an ethnic studies class to graduate, starting with the class of 2030. That means the state needs lots of new ethnic studies teachers. But do educators need a special credential to teach ethnic studies? Some ethnic studies advocates say allowing any social science teacher to instruct the subject will lead to watered down and ineffective courses, while school districts argue that flexibility is important if they’re going to fill the roles.

By Megan Tagami

CalMatters

California high school students will be required to pass an ethnic studies class to graduate, starting with the class of 2030. That means the state needs lots of new ethnic studies teachers. But do educators need a special credential to teach ethnic studies? Some ethnic studies advocates say allowing any social science teacher to instruct the subject will lead to watered down and ineffective courses, while school districts argue that flexibility is important if they’re going to fill the roles.

On a rainy Friday afternoon at Santa Monica High School, ethnic studies teacher Marisa Silvestri introduced her class to the rap song “Kenji.” As singer Mike Shinoda narrated his family’s experiences in the Japanese American incarceration camps of World War II, Silvestri’s class fell silent. After the last bars of music filled the room, the class set to work analyzing the song’s lyrics, agreeing that Shinoda humanized a historical event some students previously knew little about.

Now in her second year of teaching ethnic studies, Silvestri said she has gone through several iterations of her curriculum – and she expects more changes to come in the future. She has studied California’s ethnic studies model curriculum, attended workshops at local universities and sought the advice of ethnic studies teachers from other school districts.

But Silvestri has never received a teaching credential in ethnic studies. Whether that’s important or not is a question California officials are weighing now that the state has become the first in the nation to require that high school students take at least one semester of ethnic studies before graduation.

California needs more ethnic studies teachers, quickly. Under the new law, passed in 2021, high schools must begin offering ethnic studies courses in the 2025-26 school year, and students in the class of 2030 will be the first ones subject to the graduation requirement. As many high schools expand their course offerings ahead of schedule, universities are grappling with how to best prepare the next generation of teachers.

Some advocates and educators have called for the creation of a specific ethnic studies credential authorizing educators to teach the relatively new and politically fraught subject in middle and high schools. They say that without such a credential, the state risks having low-quality classes that can do more harm than good. But others worry that an additional requirement may make it even harder for the schools to find teachers for the subject.

State regulations allow teachers with a social science credential to teach ethnic studies, said Jonathon Howard, government relations manager for California’s Commission on Teacher Credentialing. However, when ethnic studies is combined with other subjects, such as reading or art, teachers from other subject areas are also eligible.

“We have all these teachers who have great hearts, who are really social justice minded, who really want to do ethnic studies because they’re thinking about themselves as, ‘I’m a culturally responsive teacher,'” said Theresa Montano, a professor of Chicana and Chicano studies at Cal State Northridge. “But that isn’t enough to give you the knowledge you need.”

Ideally, Montano said, teachers should have an undergraduate degree in ethnic studies, plus an ethnic studies credential that would show them how to translate their expertise into classroom curriculum.

Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo agrees. In February, she introduced legislation requiring the Commission on Teacher Credentialing to begin creating an ethnic studies credential by 2025.

“The social science credential program does not cover ethnic studies sufficiently,” Carrillo, a Democrat from Los Angeles, said by email. “We maintain that at the present time there is no existing credential that sufficiently covers the depth and breadth of the multidisciplinary nature of Ethnic Studies.”

The commission would need authorization from the Legislature to begin developing a new credential, Howard said.

However, some school districts say the current flexibility around teacher requirements has worked to their benefit, allowing them to expand their ethnic studies course offerings ahead of schedule.

Santa Rosa City Schools has been offering ethnic studies courses since 2020 and currently requires students to take a full year of the subject before graduation. Because several classes, from English to dance, incorporate ethnic studies into the course material, all teachers are eligible to teach the subject, said Tim Zalunardo, the executive director of educational services. He added that this approach makes it easier for the school to recruit teachers who are excited and willing to teach ethnic studies.

“It provides flexibility on both the students and on the school’s course offerings,” Zalunardo said.

A controversial subject

Debates around ethnic studies are nothing new.

Ethnic studies began at San Francisco State University in the late 1960s as students pushed for the creation of classes dedicated to studying the histories and cultures of people of color. As the subject gained momentum – and criticism – across the nation, advocates began to push for its inclusion in K-12 schools.

In 2021, after two years of drafting and heated debate, the State Board of Education adopted an ethnic studies model curriculum that primarily focuses on the untold “histories, cultures, struggles, and contributions” of Black, Latino, Native American and Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. Although districts are not required to use the curriculum, it provides schools with guidance on how to implement the subject and offers sample lessons.

Later that year, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the new graduation requirement into law, even as parents and school board members denounced ethnic studies in Orange County and other areas of the state. Future teachers still remain divided on the necessity of the subject.

Christine Soliva, a graduate student in UC Riverside’s teacher education program, said some of her peers critiqued an ethnic studies class they took in the fall, challenging the importance of incorporating an ethnic studies framework into their math or science courses. She added that while she would pursue an ethnic studies credential if it were available, she is unsure if other teacher candidates would be equally receptive.

“It really is just like, are educators willing to take that next step to be able to think outside the box and challenge themselves and their ideals to look at curriculum and content through an ethnic studies lens?” Soliva said.

Former Assemblymember Jose Medina, who authored the legislation requiring ethnic studies in high schools, said he does not believe the controversy around the subject will prevent state leaders from having necessary conversations about how to best prepare teachers.

“I think, despite the controversy, the state will be well prepared to have teachers in place by the time of the requirement,” he said.

But not everyone shares Medina’s optimism.

As hundreds of high schools begin rolling out new courses in the coming years, the state may face a shortage of ethnic studies teachers, said Lange Luntao, the director of external relations at The Education Trust-West, a nonprofit that advocates for educational equity. Ethnic studies graduation requirements are already in effect at some of the state’s large school districts, including Los Angeles Unified, San Diego Unified and Fresno Unified.

“I think one fear is that we’re going to open up enrollment for ethnic studies classes, and not have enough educators who have experience with this content,” he said.

Preparing future teachers

In the absence of an ethnic studies credential, California’s universities have developed a range of programs preparing students for teaching the subject. Some offer classes on ethnic studies teaching methods and curriculum development, while others place students in ethnic studies classrooms to gain firsthand experience.

At UC Riverside, students earning their teaching credential can pursue an ethnic studies pathway made up of elective courses dedicated to ethnic studies teaching methods and curriculum.

Karl Molina, a UC Riverside master’s student earning his social sciences credential through the program, works as a student teacher of high school economics, sociology and government in the Riverside Unified School District. Earlier in the school year, Molina introduced a sociology lesson named after rapper Tupac Shakur’s poem, The Rose That Grew from Concrete. He instructed his students to analyze Shakur’s poem and reflect on how the concepts of social and familial capital applied to their own lives. In discussions, students decided that capital was more than monetary wealth – it included the languages, cultures and aspirations that shaped their lives, Molina said.

“They were really, really into it,” Molina said. “I was really excited to get going and move forward.”

But as a student teacher, Molina has limited control over the course curriculum and had to cut his lesson short. If he were teaching in an ethnic studies classroom as part of a formal ethnic studies credentialing program, he said, he might have had more freedom to pursue it.

“We’re not indoctrinating these students,” Molina said. “We’re just telling them, ‘You have so much wealth. Here’s where your wealth is, and here’s what it does for you.'”

At San Jose State University, some students already have the opportunity to see ethnic studies taught in real time through an Ethnic Studies Residency Program that places students into an ethnic studies classroom for a full academic year.

In his residency at Evergreen Valley High School, Eduardo Zamora instructs his students to partner up, facing one another in concentric circles. He first asks students to answer a silly icebreaker – example: “Would you rather be in the history books or gossip magazines?” – before moving onto questions about recent lessons. In one instance, he asked students to share one-minute reflections on the documentary Immigration Nation and how it relates to their discussion on Central American migration and racism in the United States. The circles rotate so students talk to a new partner each time.

“They’re moving, they’re talking and it’s educational,” said Zamora, a student in San Jose State University’s teacher education program who is pursuing a social sciences credential.

He said he hopes to bring the same activity into his own ethnic studies classroom one day, adding that his residency has shown him the importance of building community and trust among his students.

Yet, while Zamora believes his residency program is preparing him well, he said an ethnic studies credential may be necessary for a widespread rollout of ethnic studies courses. Currently, San Jose State University’s residency program only takes three to four students a year.

“One of the students came up to us saying that our class was very diverse, bringing in perspectives of people of color. And then she mentioned that her history teacher … said it’s easier to teach history just through ‘the normal way,’ I guess the Eurocentric way,” Zamora said. “So I think a specific ethnic studies credential is probably needed.”

Training the current workforce

As universities shape the next generation of ethnic studies teachers, districts are left with the challenge of preparing their current workforce to teach the subject.

In Elk Grove Unified School District, high schools have offered ethnic studies courses since 2020. But Robyn Rodriguez, a parent in the district and former Asian American Studies professor at UC Davis, said she’s concerned that Sacramento-area schools may be placing social studies teachers in ethnic studies classrooms without adequate preparation for the subject.

“You either see very watered down versions of ethnic studies, or ethnic studies being very nominally implemented,” she said.

Rodriguez’s son is only in second grade, but she said she is already supplementing his language arts curriculum with other reading because the texts assigned were not from diverse authors. As for what ethnic studies might look like by the time her son reaches high school, Rodriguez said, “I’m absolutely worried.”

Silvestri, the Santa Monica High School teacher, said she is torn about the necessity of an ethnic studies credential, adding that she would not want it to prevent interested and passionate teachers from teaching the subject. However, she said, the credential could help streamline the professional development opportunities she has needed to seek out independently over the past few years.

The University of California’s California History-Social Science Project works to support people like Silvestri who are teaching ethnic studies for the first time. Dominique Williams, the project’s ethnic studies coordinator, offers workshops educating teachers about the history of ethnic studies instruction and shows them how they can teach historical narratives from new perspectives.

Williams draws on her own experience transitioning from teaching English and social studies to ethnic studies in the Sacramento City Unified School District.

“In hindsight, I think that there is more training that I could have had, that I’m now trying to make sure that teachers are getting as they start their own journeys,” Williams said.

As the debate surrounding ethnic studies teacher preparation continues, Jayla Johnson-Lake, a sophomore at Santa Monica High School, said a passion for teaching is just as important as any credential. Johnson-Lake said Silvestri’s ethnic studies class has surpassed her expectations, introducing her to new facts, such as the details of Japanese internment and how the Black Codes worked to restrict Black people’s rights in the post-Civil War era.

“I believe it’s important to have a teacher who wants to teach the class,” Johnson-Lake said.

Activism

Losing Income Chief Cause of Homelessness, UCSF Study Finds

Losing income is the No. 1 reason Californians end up homeless — and the vast majority of them say a subsidy of as little as $300 a month could have kept them off the streets. That’s according to a new study out of UC San Francisco that provides the most comprehensive look yet at California’s homeless crisis.

By Marisa Kendall

CalMatters

Losing income is the No. 1 reason Californians end up homeless — and the vast majority of them say a subsidy of as little as $300 a month could have kept them off the streets.

That’s according to a new study out of UC San Francisco that provides the most comprehensive look yet at California’s homeless crisis.

In the six months prior to becoming homeless, the Californians surveyed were making a median income of just $960 a month. The median rent for a two-bedroom apartment in California is nearly three times that, according to Zillow. And though survey participants listed a myriad of reasons why they lost their homes, more people cited a loss of, or reduction in, income than anything else.

The study’s authors say the findings highlight the idea that money, more than addiction, mental health, poor decisions or other factors, is the main cause of — and potential solution to — homelessness.

“I think it’s really important to note how desperately poor people are, and how much it is their poverty and the high housing costs that are leading to this crisis,” said Margot Kushel, a physician who directs the UCSF Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative, which conducted the study.

Already the study — which the authors say is the most representative homelessness survey conducted in the U.S. since the mid-1990s — has drawn attention from high places.

The initial idea for the survey came from California Health and Human Services Secretary Mark Ghaly, Kushel said. Ghaly’s office has been involved along the way, though the state didn’t fund the research.

“As we drive toward addressing the health and housing needs of Californian’s experiencing homelessness, this study reinforces the importance of comprehensive and integrated supports,” Ghaly said in a news release. “California is taking bold steps to address unmet needs for physical and behavioral health services, to create a range of housing options that are safe and stable, and to meet people where they are at. We are grateful for the voices of those who participated in this study, as they will help guide our approach.”

The survey comes as local governments press Gov. Gavin Newsom to distribute ongoing funding to fight homelessness, arguing the one-time grants he has doled out so far don’t allow them to make lasting progress. Newsom has resisted that kind of multi-year commitment, although his administration has allocated nearly $21 billion toward homelessness and housing since he took office.

The UCSF team surveyed 3,198 unhoused adults throughout California between October 2021 and November 2022, and conducted in-depth interviews with 365 of those participants.

What drives California’s homeless crisis?

When asked why they left their last home, respondents cited conflict between roommates, not wanting to impose on the person or people they were living with, domestic violence, illness and breakups.

A loss of or reduction in income was the most common response, with 12% of people saying that’s what caused their homelessness. Just 4% blamed their own substance use or drinking.

All of those varied factors that led people to lose their homes often have underlying roots in economic instability, said Jennifer Wolch, a professor emerita at UC Berkeley specializing in homelessness.

“This lack of income and severe instability and housing precarity, it has spillover effects on people’s relationships, their use of alcohol and other kinds of problematic substances,” she said. “It impinges on their health status.”

The story told by one survey participant, identified as Carlos, shows how someone can gradually descend into homelessness. He had to stop working after falling off a ladder and injuring his spine, but wasn’t eligible for workers’ compensation because he had been paid in cash. Unable to afford his rent, he moved out of his apartment and rented a room in a new place. He soon left due to conflicts with his roommates. He then briefly lived with his sister’s family, until they faced COVID-related job loss and he moved out to avoid becoming a burden. He lived in his truck until it was towed due to unpaid parking tickets. Now, he lives in an encampment in a park.

Most of the homeless Californians surveyed said a relatively small amount of cash would have saved them from the street. Seventy percent said a monthly rental subsidy of $300-$500 would have kept them from becoming homeless, while 82% believed a one-time payment of between $5,000 and $10,000 would have worked.

Jennifer Loving, CEO of Santa Clara County nonprofit Destination: Home, hopes the study’s findings will help debunk what she says is a common myth that people are homeless because of their individual failings, rather than because rents are outpacing wages. She’d like to see California’s leaders take notice.

“Hopefully it will inform a statewide strategy,” she said, “because we need a statewide strategy to be able to manage how we are addressing homelessness.”

Another California homeless myth

Another myth the study attempts to dispel is that most homeless people flock to California cities because of warm weather, liberal policies and generous services. In reality, 90% of the people surveyed said they were last housed in California, and 75% live in the same county as where they lost their housing.

That’s important to remember, Wolch said, because it’s easy to disregard unhoused people who we think “aren’t from here” and haven’t paid taxes here.

“People who are homeless are your neighbors,” she said. “People who are homeless live in the same city that you do and they possibly have lived there longer than you have.”

The survey painted a bleak picture of the traumas and tragedies that made survey participants more vulnerable to ending up on the street. People reported growing up in depressed communities with few job opportunities, where they experienced exploitation and discrimination. Nearly three-quarters said they had experienced physical violence during their lives, and one-quarter had experienced sexual violence.

One in three people surveyed attempted suicide at some point.

Mental health and addiction also were a common undercurrent in the lives of many of the unhoused people surveyed, which is to be expected in a population that has suffered so much trauma, according to the researchers. Two-thirds of people reported experiencing mental health symptoms — including depression, anxiety or hallucinations — in the past 30 days. Homelessness and all it entails, including lack of sleep, violence and difficulty accessing medication, exacerbated their symptoms, many people said.

About one-third of people reported using drugs three or more times a week — mostly methamphetamines. And 1 in 5 people who reported regular drug or heavy alcohol use said they wanted addiction treatment but couldn’t get it.

Jail to homelessness pipeline

The study also emphasizes the relationship between incarceration and homelessness, said Alex Visotzky, senior California Policy Fellow for the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

More than three-quarters of people surveyed had been incarcerated at some point during their life. And in the six months before becoming homeless, 43% were in jail or prison, or were on probation or parole. The vast majority of those who had been incarcerated received no help signing up for housing, healthcare or benefits upon release.

“That drove home for me this point: Incarceration, homelessness and then subsequent criminalization are fueling a really vicious cycle for marginalized people, especially Black and Latino Californians, that’s both causing and prolonging homelessness,” Visotzky said.

‘We don’t have enough housing for poor folks’

To solve the homelessness crisis, the main problem California needs to address is the lack of housing that’s affordable for extremely low-income residents, according to the researchers. The state has just 24 affordable and available homes for every 100 extremely low-income households, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Among the solutions the researchers proposed: expanding vouchers that use federal, state and local dollars to subsidize people’s rent. They also suggested piloting shared housing programs where multiple households live together and split costs, while also providing funds to help people remain with or move in with family or friends.

Kushel hopes the study helps drive public support for these ideas, which in turn will spur politicians to act.

“I hope that it really focuses our efforts on housing, which is the only way out of homelessness,” Kushel said. “It’s almost so obvious it’s hard to speak about. We don’t have enough housing for poor folks.”

The study is available at https://homelessness.ucsf.edu/our-impact/our-studies/california-statewide-study-people-experiencing-homelessness.

Copyright © 2023 Bay City News, Inc. All rights reserved. Republication, rebroadcast or redistribution without the express written consent of Bay City News, Inc. is prohibited. Bay City News is a 24/7 news service covering the greater Bay Area.

Bay Area

‘Godzilla Next Door’: How California Developers Gained New Leverage to Build More Homes

It’s hard to know just how many builder’s remedy projects have been filed across the state. YIMBY Law, a legal advocacy group that sues municipalities for failing to plan for or build enough housing, has a running count on its website of 46 projects, though its founder, Sonja Trauss, admits that it’s an imperfect tally.

By Ben Christopher

CalMatters

Late last fall, a Southern California developer dropped more than a dozen mammoth building proposals on the city of Santa Monica that were all but designed to get attention.

The numbers behind WS Communities’s salvo of proposals were dizzying: 14 residential highrises with a combined 4,260 units dotting the beachside city, including three buildings reaching 18 stories. All of the towers were bigger, denser and higher than anything permitted under the city’s zoning code.

City Councilmember Phil Brock attended a town hall shortly after the announcement and got an earful. A few of the highlights: “Godzilla next door,” “a monster in our midst” and “we’re going to never see the sun again.”

“‘Concerned’ would be putting it mildly,” Brock said of the vibe among the attendees. “A lot of them were freaked.”

As it turns out, freaking locals out may have been the point.

WS Communities put forward its not-so-modest proposal at a moment when it had extreme leverage over the city thanks to a new interpretation of a 33-year-old housing law. Santa Monica’s state-required housing plan had expired and its new plan had yet to be approved. According to the law, in that non-compliance window, developers can exploit the so-called builder’s remedy, in which they can build as much as they want wherever they want so long as at least 20% of the proposed units are set aside for lower income residents.

Over the last two years, local governments across California have had to cobble together new housing plans that meet a statewide goal of 2.5 million new units by 2030. At last count, 227 jurisdictions — home to nearly 12 million Californians, or about a third of the state population — still haven’t had their plans certified by state housing regulators, potentially opening them up to builder’s remedy projects.

That gives developers a valuable new bargaining chip.

WS Communities used its advantage in Santa Monica to broker a deal in which it agreed to rescind all but one of its 14 builder’s remedy projects in exchange for fast-tracked approval of 10 scaled-down versions.

“The builder’s remedy — the loss of zoning control, the ability of a developer to propose anything, Houston-style, whatever they want, no zoning regulations — that gets people’s attention,” said Dave Rand, the land-use attorney representing the WS Communities. “The builder’s remedy can be a strategic ploy in order to potentially leverage a third way.”

For the developer, the settlement — which still needs a final vote to fully be implemented — is a major win. But this use of a long-dormant law also represents a shift in the politics of housing in California, reflecting a new era of developer empowerment bolstered by the growing caucus of pro-building lawmakers in the Legislature.

“The old games of begging municipalities for a project and reducing the density to get there and kissing the ass of every councilmember and planning official and neighbor — that’s the old way of doing things,” said Rand. “Our spines are stiffening.”

It’s hard to know just how many builder’s remedy projects have been filed across the state. YIMBY Law, a legal advocacy group that sues municipalities for failing to plan for or build enough housing, has a running count on its website of 46 projects, though its founder, Sonja Trauss, admits that it’s an imperfect tally.

Some of the projects, like those in Santa Monica, are towers with hundreds of units. Others are more modest apartment buildings. Whatever the total, Trauss said it represents a significant uptake for a novel legal strategy.

“There were a lot of naysayers who were like ‘it’s too risky,’ ‘nobody knows what’s gonna happen,’ ‘nobody’s gonna do it,’ blah, blah, blah,” she said. “I feel vindicated. You know, people are trying it.”

But counting just the units proposed under the law misses its broader impact, said UC Davis law professor Chris Elmendorf.

Multiple cities rushed forward their housing plans this year, with city attorneys, city planners and councilmembers warning that failure to do so before a state-imposed deadline could invite a building free-for-all.

“All the action is in negotiation in the shadow of the law,” said Elmendorf. The law “may result in a lot of other projects getting permitted that never would have been approved because the developer had this negotiating chip.”

Rediscovering the California builder’s remedy

If it’s possible for someone to unearth a forgotten law, Elmendorf can rightly claim to have excavated the builder’s remedy.

The Legislature added the provision to the government code in 1990, but no one used it for decades. In the one case Elmendorf found where someone tried — a homeowner in Albany, just north of Berkeley, who wanted to build a unit in his backyard in 1991 without adding a parking spot — local planners shot down the would-be builder.

Elmendorf stumbled upon the long-ignored policy 28 years later while researching East Coast laws that let developers circumvent zoning restrictions in cities short on affordable housing.

He started tweeting about it. He even dubbed the California law the “builder’s remedy,” borrowing the coinage from Massachusetts.

“I think it’s fair to say that people in California had forgotten about the builder’s remedy almost completely until I started asking about it on Twitter,” he said. ” I think those twitter threads led some people to say, ‘huh.'”

Among those who noticed: staff at the state Housing and Community Development department who began listing the “remedy” as a possible consequence of failing to plan for enough housing.

Why was the builder’s remedy largely forgotten? The text of the law is complicated and it’s only relevant once every eight years, when cities and counties are required to put together their housing plan. Plus, though it allows developers to ignore a city’s zoning code, it’s not clear that it exempts them from extensive environmental review, making the cost savings of using it uncertain.

But more importantly, up until recently, invoking the builder’s remedy — the regulatory equivalent of a declaration of war — was bad for business.

Historically, local governments have had sweeping discretion over what gets built within their borders, where and under what terms and conditions. Developers and their lawyers hoping to succeed in such a climate had to excel at what one land use attorney dubbed the art of “creative groveling.”

But in recent years, as the state’s housing shortage and resulting affordability crisis have grown more acute, lawmakers have passed a series of bills to take away some of that local control. In many cases, cities and counties are now required to approve certain types of housing, like duplexes, subsidized housing apartments and accessory dwelling units, as long as the developer checks the requisite boxes.

That’s all led some developers to rethink their approach to dealing with local governments — one that is less concerned with building bridges and isn’t so afraid to burn a few.

Santa Monica makes a deal

Santa Monica’s city council voted unanimously for the deal with WS Communities early last month — but grudgingly.

In exchange for the developer pulling its original proposals, the city agreed to a streamlined approval process for the new plans. The council also agreed to pass an ordinance to give the developer extra goodies on the 10 remaining projects.

If the city doesn’t pass the ordinance, according to the settlement, WS Communities has the right to revive the builder’s remedy for all 14 towers.

Councilmember Brock, elected in 2020 along with a slate of development-skeptics, was hardly a fan of the deal. But as he saw it, the prospect of a lengthy legal battle that the city’s attorney insisted Santa Monica would lose gave the council little choice. That didn’t make what Brock viewed as a hard-knuckle negotiating tactic any easier to swallow.

“I don’t believe for a minute that they ever planned to build all those projects,” he said.

Councilmember Caroline Torosis, who was elected last fall, laid the blame on the prior council for failing to pass a timely housing plan. Even so, she said the city had no choice but to reclaim control over its own land use from the developer.

“We were put in a difficult situation,” she said. “I think that this was absolutely the best negotiated settlement that we could have reached, but of course, they had leverage.”

Both Scott Walter, the president of WS, and Neil Shekhter, the founder of the parent company, NMS Properties, refused a request to be interviewed through their lawyer, Rand.

But in true property kingpin fashion, WS was able to flip these builder’s remedy proposals into things of even greater value: ironclad plans that it can build out quickly or sell to another developer.

“The builder’s remedy projects were anything but fast and certain,” said Rand. “This has been parlayed into something with absolute certainty and front-of-the-line treatment.”

Affluent California cities fight back

About an hour’s drive northeast of Santa Monica, the foothill suburb of La Canada Flintridge recently rejected a builder’s remedy application.

During a May 1 hearing, Mayor Keith Eich stressed the city was “not denying the project.” Instead, they were denying that the builder’s remedy itself even applied to the city.

The argument: The housing plan the council passed last October complies with state law. California’s Housing and Community Development department rejected that version of the plan and has yet to certify a new one. But La Canada’s city attorney, Adrian Guerra argued at the hearing that the agency’s required changes were minor enough to make the October plan “substantially” compliant.

That’s not how state regulators see it. In March, the housing department sent the city a letter of “technical assistance.”

“A local jurisdiction does not have the authority to determine that its adopted element is in substantial compliance,” the letter reads.

Not so, said Guerra: “The court would make that determination.”

A number of cities across the state have made that argument. Among them are Los Altos Hills and Sonoma. Beverly Hills is already fending off a lawsuit contending that the law applies to that city, though it recently rejected a builder’s remedy project on extensive technical grounds.

It’s a question that’s almost certain to end up in court. A recent California’s Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal ruling offers legal fodder to both sides.

The April opinion ruled against the state housing department’s certification of the City of Clovis’ housing plan. That’s a point for those arguing that the word of state regulators is not inviolate. But the ruling also noted that courts “generally” defer to the state agency unless its decision is “clearly erroneous or unauthorized.”

Down the coast, the City of Huntington Beach isn’t relying on such legal niceties. In March, the city council passed an ordinance banning all builder’s remedy projects under the argument that the law itself is invalid. Days later, the Newsom administration sued the city.

But in Santa Monica, city council members didn’t see much upside in pushing back.

“You can’t just fight a losing battle,” Brock said. “I think anybody who decides they’re gonna be an all star NIMBY is up for failure.”

CalMatters

A California Law Forced Police to Release Shooting Footage; Now Videos Follow the Same Script

Ken Pritchett clicks his mouse and the logo of a Southern California police department pops up on a computer monitor the width of his shoulders. Another click and the image flips to a three-dimensional map. A glowing orange arrow indicates the direction a man ran as he tried to evade police. “Right here, this is the path he took in the alley,” Pritchett said, switching from the map to a still image highlighting an object in the man’s hand. “Then you can see him turn toward the officers. He wants to die. This is suicide.”

By Nigel Duara

CalMatters

Ken Pritchett clicks his mouse and the logo of a Southern California police department pops up on a computer monitor the width of his shoulders. Another click and the image flips to a three-dimensional map. A glowing orange arrow indicates the direction a man ran as he tried to evade police.

“Right here, this is the path he took in the alley,” Pritchett said, switching from the map to a still image highlighting an object in the man’s hand. “Then you can see him turn toward the officers. He wants to die. This is suicide.”

This incident, like all the videos Pritchett produces in his home office, ended in a police shooting. Pritchett has made more than 170 of these for police departments and sheriff’s offices, mostly in California.

The video flips again, this time to the display of a shuddering body camera worn by an officer sprinting down an alley. Commands are yelled, the person being chased lifts an object with his right hand, police fire their weapons, the man falls down.

The video isn’t much different from hundreds of others produced since California passed a law in 2018 mandating police departments release body camera footage within 45 days of any incident when an officer fires a gun or uses force that leads to great bodily injury or death. Like most other critical incident videos released by law enforcement agencies after a shooting, this one is a heavily edited version of the original raw video, created by one of the private contractors that went into business editing police footage after the law went into effect.

Pritchett, who makes more of these videos than any other private contractor in California, asked CalMatters not to disclose the name of the police department in order to preserve their business relationship.

The law has some exceptions, allowing departments to withhold video if it would endanger the investigation or put a witness at risk. Law enforcement departments often cite those reasons when regularly denying records requests by CalMatters and other news organizations. Of the 36 fatal police shooting cases since July 2021 being tracked by CalMatters, only three have responded with even partial records.

Instead, the public and the media must rely on edited presentations that often include a highlighted or circled object in a person’s hand, slowed-down video to show the moments when the person may have pointed the object at police and transcriptions of the body camera’s audio.

They are also the only documentation of a fatal police encounter that the public will see for months, or years, or maybe ever.

Since the advent of cell phone cameras and, later, police-worn body cameras, the public has had detailed access to violent police encounters in a way it never had before. After incidents including the livestream of the aftermath of the Minnesota police shooting of Philando Castile in 2016 and the helicopter footage of the Sacramento police shooting of Stephon Clark in 2018, states including California passed a host of laws aimed at using that technology to better judge the actions of officers.

Critics allege that the problem with the condensed, heavily-edited version of the body camera footage released by law enforcement agencies is that they shape public opinion about a person’s death or injury at the hands of the police long before the department in question releases all the facts in the case or the full, raw video.

They also point to particular incidents in which a department erased or failed to transcribe audio critical to understanding the case, did not make clear which officers fired their gun or cut the video at a critical moment. In one case, Los Angeles journalist Sahra Sulaiman has taken apart multiple videos released by the Los Angeles Police Department and found irregularities that she asserts are deliberate manipulations meant to justify officers’ actions. In response, she said the LAPD ignores her or directs her back to the video.

“To only release an edited version is not what we think is called for from the defendant’s point of view,” said Stephen Munkelt, executive director of California Attorneys for Criminal Justice, a Sacramento-based association of criminal defense attorneys. “If they’re editing things out, it’s probably the stuff that’s beneficial to the defendant.”

He also worries about the impact of the release of the body camera footage on a potential jury pool. Still, Munkelt said, some video is better than none, if only because defense attorneys have more grounds to ask a judge for the full, unedited video.

Former journalist working with California police

In response to the 2018 body camera law, a cottage industry has emerged to produce these videos, though several larger law enforcement agencies produce theirs in-house. Pritchett works for Critical Incident Video, founded, not coincidentally, when the law went into effect in 2019. According to emails obtained by The Appeal and The Vallejo Sun, Critical Incident Video charges $5,000 per video.

Pritchett is a former journalist and insists that he applies the same scrutiny and objectivity to these videos, paid for by police departments, that he did in his former life as a television reporter and anchor in Fresno and Sacramento.

“Virtually every article we’ve seen about what we do, somebody accuses us of spinning for the police department, but I have yet to ever see an example put forward that shows that we’re spinning anything,” he said. “And if they did, tell me, for God’s sakes. My entire goal is to make these straight, spin-free.”

Not every department uses Critical Incident Video, but for the dozens that do, Pritchett’s style is unmistakable: first, the map, then usually a transcription of 911 calls, then the body camera video. Pritchett said that, if he’s done his job well, he can help head off conflict between a law enforcement agency and the public.

“I think the main issue now is people come jumping to conclusions about what happened before they’ve seen the video, which is why we recommend that (law enforcement) always get that video out there as quickly as possible,” Pritchett said. “We have done quite a few videos where there was a social media public narrative about something that happened, and the video clearly shows that that didn’t happen.”

Pritchett said that, before he made his first video, he learned by watching the videos that departments produced internally. He did not like what he saw.

“Basically, what we saw was the LAPD’s videos, and I didn’t like them … I probably shouldn’t have said that,” he said with a laugh. “But I remember seeing mugshots. I remember seeing information that was not really relevant (like) previous charges. I remember thinking the whole (video) that someone had a gun, until they told me at the end that it was actually not a gun.”

So, he has rules. He will not refer to the person who was shot as a “suspect.” He will not use mugshots of the person who was shot. He will not display previous charges or convictions of the person shot, even if the department asks him to — something that he said cost his company a client when the police department insisted on including it. If an object was later found to be anything other than a gun, he demands that the departments tell viewers that up front.

Critical Incident Video’s process usually begins hours after a shooting. The police department or sheriff’s office will call Pritchett and send the raw footage, along with any witness video the agency has obtained. He combs through it, picking out the parts he believes are important.

He reads the initial police press release — “which is often incorrect,” he said — then reads any related media reports. He transcribes the audio of the body camera, creates a 3D map showing where the encounter began and writes a prospective script if one is requested, then tells the police to put it in their own words.

Pritchett said he pushes back against departments. Sometimes in a press release, agencies will say they immediately rendered first aid to a person they shot, but the video shows a delay.

“Sometimes that becomes a point of contention,” Pritchett said. “I’m looking at the video and say, well, how do you define immediate? We’ll change that. Like I said, we have to fight.”

The California Police Chiefs Association and the California State Sheriffs’ Association did not return voicemails from CalMatters for this story.

Assemblymember Phil Ting, a San Francisco Democrat who wrote the 2018 body camera law, said he has no problem with the condensed videos provided by law enforcement agencies after a shooting, because they’re much better than what was made public before the law.

“After the legislation was passed into law, we’ve seen so much more released and so much more video,” Ting said. “If a department is articulating why they acted in a particular way, that’s a good thing. They work for the public and we want accountability.”

Michele Hanisee, president of the Los Angeles Association of Deputy District Attorneys, said the release of the videos is a balancing act, forcing prosecutors to weigh the benefit of transparency against the potential harm of prejudicing the jury pool.

“While transparency promotes public confidence in the conduct of law enforcement,” Hanisee wrote in an email to CalMatters, “the pre-trial release of evidence has the potential to influence the testimony of witnesses, create bias in potential jurors, or create an environment that could justify a change in venue.”

Replaying LAPD shooting videos

Three hundred and sixty miles south of Pritchett’s Sacramento home office, Sulaiman, a communities editor for StreetsBlog Los Angeles, is in front of her own monitor, squeezed into the two-foot patch of carpet between her couch and a knee-high table on which her laptop is perched.

Her eyes, reflected back in the dark blue of a police uniform on screen, dart back and forth between the video released by the LAPD and the time code. She rewinds, presses play, pauses the video, rewinds again.

“Did you hear it?” she asks, then presses play on the video from December 2021. “Listen again.”

On screen is Margarito Lopez, a developmentally disabled 22-year-old sitting on a set of short stairs, holding a meat cleaver, bathed in blue and red light. Several LAPD patrol cars are parked in front of him, the officers shouting at him to drop the cleaver, as they have for at least five minutes.

Lopez stands. The police continue to shout in English and in Spanish. He holds the cleaver over his head. The body camera video’s transcription matches the words of the officers: “Hey, drop it, drop it, stop right there!”

Seconds later, officers fire live rounds, killing Lopez. Sulaiman rewinds again and turns up the volume on her laptop.

This time, a piece of audio that wasn’t transcribed by the LAPD is clear: “Forty, stand by.”

Forty, in this case, is code for a less-lethal foam projectile, a warning to other officers that what they’re about to hear are not lethal rounds.

“The protocol demands that they give the warning and then everybody stand down, wait to see what effect it has,” she said. “So he gives the warning and if you don’t know what you’re listening for, you just hear shouting. But then I realized that that’s what the warning was, and immediately, as soon as the less lethal is fired, it’s contagious fire because they didn’t hear the warning.”

Without that piece of audio, Sulaiman said, the video makes it appear that Lopez was shot after failing to comply with commands and advancing toward the officers.

“And that’s where they play with these transcriptions a little bit,” she said. “So that’s the kind of thing where if you have this different piece of information, that completely changes what this incident is.”

Sulaiman doesn’t believe the LAPD transcription left out the less-lethal warning by accident. The LAPD did not respond to specific questions from CalMatters about this incident or the video transcription.

Since the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May 2020, Sulaiman has focused her work almost entirely on police violence.

Among her most thorough investigations was when she found the only evidence that an LAPD sergeant fired his weapon from his vehicle without stopping during a police chase on July 18, despite two other officers determining moments earlier that the man being chased didn’t have a gun.

The video never made clear which officer fired the shot that wounded 39-year-old Jermaine Petit, but in the reflection in the glass of the sergeant’s patrol car dashboard, she saw him holding up his gun and pointing it out the passenger side window. At the time of the shooting, the sergeant’s arm jerks backward. She said she had to watch the video several times, including at one-quarter speed, before she noticed the reflection.

She acknowledges that police have a difficult job in often-chaotic circumstances, trying to make life-or-death decisions. But that, she said, is their job.

“A lot of times they’ll say, oh, when we put civilians through these active shooter sort of scenarios, they just fire willy-nilly at people,” she said. “Well, yeah, ’cause I’m not f——- trained.

“And when you go second-by-second through these, it is certainly a lot easier to play Monday morning quarterback. But you also see that LAPD is doing the same thing when they’re constructing these narratives.”

Sulaiman said the videos themselves are a mixed bag of consequences. She’s glad that there is some video evidence of the shootings released, but said the format is ripe for manipulation by the police.

“What these videos have taught me is how really skilled LAPD is at deflecting attention at deeper structural reform,” she said. “That they are very good at pointing the finger, at localizing blame on the things that take the least amount of tweaking to fix and deflecting any kind of interest in questions of structural reform.”

Both Sulaiman and Pritchett, in their respective jobs, have had to watch hours and hours of people being shot. The images they see are not blurred. People lie dying in pools of blood, people ask why they were shot, people shout for their mothers.

“It’s tough,” Sulaiman said. “I don’t know what else to say about it.”

When asked how viewing those videos affects him, Pritchett paused for several seconds, started to speak, stopped himself, then started again.

“To be determined.”

Copyright © 2023 Bay City News, Inc. All rights reserved. Republication, rebroadcast or redistribution without the express written consent of Bay City News, Inc. is prohibited. Bay City News is a 24/7 news service covering the greater Bay Area.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

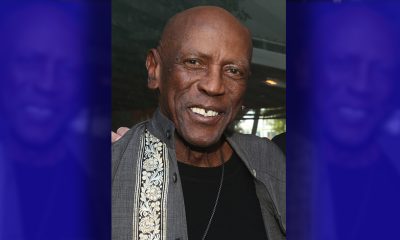

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024