Community

Cal State East Bay Helps Former Foster Youth Graduate

Tisha Ortiz chose Cal State East Bay sight unseen.

Unlike many of today’s college freshmen, the former foster youth didn’t tour campuses, compare dormitories or think about how far away she was moving from her native Southern California.

She simply chose the school that gave her the most financial aid, packed her belongings into a single suitcase and boarded a plane. That plane landed nearly 600 miles away in Oakland, where Ortiz had never been, and where Cal State East Bay’s Renaissance Scholars — a program reversing the abysmal college graduation rate for former foster youth — was waiting to welcome her.

“I had no food, no sheets, nothing,” Ortiz says. “They picked me up from the airport, got me into the dorm, got me groceries. They had a whole care package for me. I felt so welcomed.”

The fact that Ortiz made it onto that plane is impressive: She’s bounced through numerous living situations and group homes; suffered physical, sexual and emotional abuse; watched her parents fall in and out of drug use; lost her mother to terminal cancer when she was 17; and experienced homelessness many times throughout her life.

And she’s far from alone. There are 62,000 foster youth in California (the highest concentration in the nation), up to 80 percent of which express a desire to go to college.

However, only 20 percent who manage to complete high school actually attend — and somewhere between just 2 and 9 percent obtain their degrees, according to a 2012 study by the National Working Group on Foster Care and Education.

But among Cal State East Bay’s Renaissance Scholars — through a network of services including help with financial aid, priority registration for classes, and monthly events that build community among the students — the rate of success is much higher.

Program Coordinator Lael Adediji reports there are 40-45 active participants at a time and 161 students have been served since the program’s inception in 2006. Of the 161, 33 percent (53) have graduated, and another 20 percent are still active students.

Adediji also reports a 53 percent “persistence” rate, which combines graduation and retention rates to encompass students who are continuing to work toward their degrees. It’s an important number to keep track of, considering the particular set of challenges many foster students face in college and ongoing difficulties with students dropping out.

“Foster youth develop ways to survive out there. Being the loudest, strongest person on the street can work when you’re trying to protect yourself.”

“Foster youth develop ways to survive out there,” Adediji explains. “Being the loudest, strongest person on the street can work when you’re trying to protect yourself. It’s a strategy. But bring that strategy onto a college campus and you won’t last long.”

Which is another area where Renaissance Scholars bridges the gap. In addition to helping students cover their basic needs and the logistics of enrollment, and providing ongoing support, the program also creates pathways to the professional services current and former foster youth frequently need.

From groceries to books to caps and gowns, Cal State East Bay’s Renaissance Scholars program gives current and former foster youth the tools — and community — they need to succeed in college.

Ortiz, for example, was set up with West Coast Children’s Clinic, a nonprofit that provides case management and therapy services for 17-21 year olds during the critical period between leaving a foster or group home and being on their own in the community.

“It was the first time I had actual therapy that dealt with the things that happened when I was younger,” Ortiz says. “All the therapy I did before was based on ‘What’s going on in your foster home?’ and the immediate circumstances, not what was really going on with me and the trauma I experienced.”

It’s also how Ortiz came in to contact with the National Center for Youth Law, where she now works as a foster youth advocate (Ortiz has been featured in local and national media for speaking out about the over-prescription of medication to foster youth). It’s a path that has inspired her to pursue a law degree once she finishes up her criminal justice major at Cal State East Bay.

Alameda County

DA Pamela Price Stands by Mom Who Lost Son to Gun Violence in Oakland

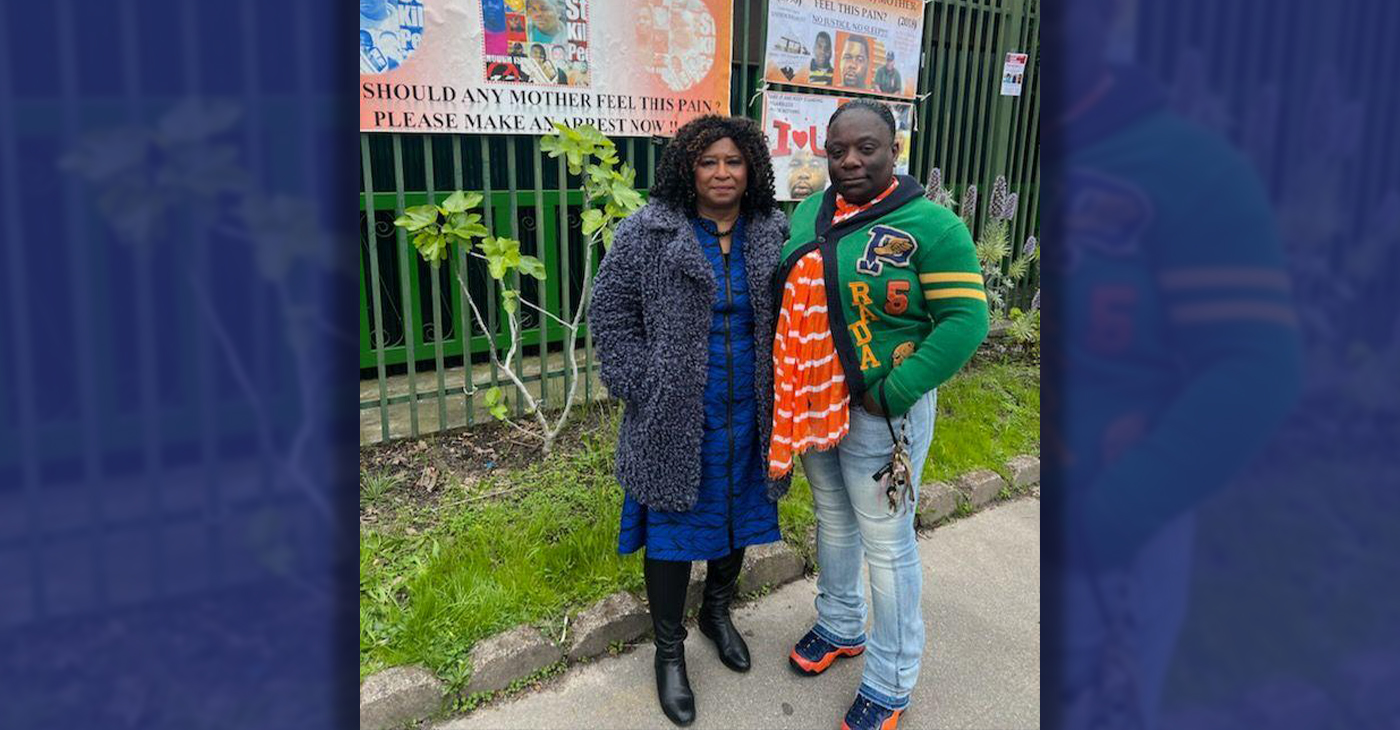

Last week, The Post published a photo showing Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price with Carol Jones, whose son, Patrick DeMarco Scott, was gunned down by an unknown assailant in 2018.

Publisher’s note: Last week, The Post published a photo showing Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price with Carol Jones, whose son, Patrick DeMarco Scott, was gunned down by an unknown assailant in 2018. The photo was too small for readers to see where the women were and what they were doing. Here we show Price and Jones as they complete a walk in memory of Scott. For more information and to contribute, please contact Carol Jones at 510-978-5517 at morefoundation.help@gmail.com. Courtesy photo.

City Government

Vallejo Welcomes Interim City Manager Beverli Marshall

At Tuesday night’s Council meeting, the Vallejo City Council appointed Beverli Marshall as the interim city manager. Her tenure in the City Manager’s Office began today, Wednesday, April 10. Mayor Robert McConnell praised Marshall’s extensive background, noting her “wide breadth of experience in many areas that will assist the City and its citizens in understanding the complexity of the many issues that must be solved” in Vallejo.

Special to The Post

At Tuesday night’s Council meeting, the Vallejo City Council appointed Beverli Marshall as the interim city manager. Her tenure in the City Manager’s Office began today, Wednesday, April 10.

Mayor Robert McConnell praised Marshall’s extensive background, noting her “wide breadth of experience in many areas that will assist the City and its citizens in understanding the complexity of the many issues that must be solved” in Vallejo.

Current City Manager Michael Malone, whose official departure is slated for April 18, expressed his well wishes. “I wish the City of Vallejo and Interim City Manager Marshall all the best in moving forward on the progress we’ve made to improve service to residents.” Malone expressed his hope that the staff and Council will work closely with ICM Marshall to “ensure success and prosperity for the City.”

According to the Vallejo Sun, Malone stepped into the role of interim city manager in 2021 and became permanent in 2022. Previously, Malone served as the city’s water director and decided to retire from city service e at the end of his contract which is April 18.

“I hope the excellent work of City staff will continue for years to come in Vallejo,” he said. “However, recent developments have led me to this decision to announce my retirement.”

When Malone was appointed, Vallejo was awash in scandals involving the housing division and the police department. A third of the city’s jobs went unfilled during most of his tenure, making for a rocky road for getting things done, the Vallejo Sun reported.

At last night’s council meeting, McConnell explained the selection process, highlighting the council’s confidence in achieving positive outcomes through a collaborative effort, and said this afternoon, “The Council is confident that by working closely together, positive results will be obtained.”

While the search for a permanent city manager is ongoing, an announcement is expected in the coming months.

On behalf of the City Council, Mayor McConnell extended gratitude to the staff, citizen groups, and recruitment firm.

“The Council wishes to thank the staff, the citizens’ group, and the recruitment firm for their diligent work and careful consideration for the selection of what is possibly the most important decision a Council can make on behalf of the betterment of our City,” McConnell said.

The Vallejo Sun contributed to this report.

City Government

Vallejo Community Members Appeal Major Use Permit for ELITE Charter School Expansion

Vallejo community members, former Solano County judge Paul Beeman and his wife Donna Beeman, filed an appeal against the approval of the Major Use Permit for the expansion of ELITE Public Schools into downtown less than two weeks after the Planning Commission approved the permit with a 6-1 vote.

By Magaly Muñoz

Vallejo community members, former Solano County judge Paul Beeman and his wife Donna Beeman, filed an appeal against the approval of the Major Use Permit for the expansion of ELITE Public Schools into downtown less than two weeks after the Planning Commission approved the permit with a 6-1 vote.

ELITE Charter School has been attempting to move into the downtown Vallejo area at 241-255 Georgia Street for two years, aiming to increase its capacity for high school students. However, a small group of residents and business owners, most notably the Beeman’s, have opposed the move.

The former county judge and his wife’s appeal alleges inaccuracies in the city’s staff report and presentation, and concerns about the project’s exemption from the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

The Beeman’s stress that their opposition is not based on the charter or the people associated with it but solely on land use issues and potential impact on their business, which is located directly next to the proposed school location.

The couple have been vocal in their opposition to the expansion charter school with records of this going back to spring of last year, stating that the arrival of the 400 students in downtown will create a nuisance to those in the area.

During the Planning Commission meeting, Mr. Beeman asked Commissioner Cohen-Thompson to recuse herself from voting citing a possible conflict of interest because she had voted to approve the school’s expansion as trustee of the Solano County Board of Education. However, Cohen-Thompson and City Attorney Laura Zagaroli maintained that her positions did not create a conflict.

“I feel 100% that the attorney’s opinion is wrong,” Beeman told the Post.

He believes that Cohen-Thompson has a vested interest in upholding her earlier vote as a trustee and is advocating for people to ratify her opinion.

Cohen-Thompson declined to comment on the Post’s story and Zagaroli did not respond for comment.

The Beeman’s further argue that the school’s presence in the commercial district could deter future businesses, including those who sell alcohol due to proximity to schools.

According to Alcohol Beverage Control (ABC), the department can deny any retail license located within 600 feet of a school. Only one alcohol selling business is located within that range, which is Bambino’s Italian restaurant at 300 feet from the proposed location.

The project’s proponents argue that the school would not affect current or future liquor-selling establishments as long as they follow the ABC agency’s guidelines.

The Beeman’s also referenced Vallejo’s General Plan 2040, stating that the proposed expansion does not align with the plan’s revitalization efforts or arts and entertainment use. They argue that such a development should focus on vacant and underutilized areas, in accordance with the plan.

The proposed location, 241 Georgia Street aligns with this plan and is a two minute walk from the Vallejo Transit Center.

The General Plan emphasizes activating the downtown with, “Workers, residents, and students activate the downtown area seven days a week, providing a critical mass to support a ‘cafe culture’ and technology access, sparking innovation and entrepreneurship.”

City staff recommended exempting the project from CEQA, citing negligible impacts. However, Beeman raised concerns about increased foot traffic potentially exacerbating existing issues like theft and the lack of police presence downtown. He shared that he’s had a few encounters with kids running around his office building and disturbing his work.

Tara Beasley-Stansberry, a Planning Commissioner and owner of Noonie’s Place, told the Post that the arrival of students in downtown can mean not only opportunities for surrounding businesses, but can allow for students to find their first jobs and continue to give back to the community in revitalization efforts.

Beasley-Stansberry had advocated for the students at the March Commission meeting, sharing disappointment in the way that community members spoke negatively of the teens.

“To characterize these children as criminals before they’ve even graduated from high school, that’s when I had to really take a look and I was kind of lost as to where we were as a city and as a community to where I couldn’t understand how we were viewing these children,” Beasley-Stansberry told the Post.

She added that the commissioners who voted yes on the project location have to do what is right for the community and that the city’s purpose is not all about generating businesses.

ELITE CEO Dr. Ramona Bishop, told the Post that they have worked with the city and responded to all questions and concerns from the appropriate departments. She claimed ELITE has one of the fastest growing schools in the county with mostly Vallejo residents.

“We have motivated college-bound high school students who deserve this downtown location designed just for them,” Bishop said. “We look forward to occupying our new [location] in the fall of 2024 and ask the Vallejo City Council to uphold their Planning Commission vote without delay.”

The Vallejo City Council will make the final decision about the project location and Major Use Permit on April 23.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoFrom Raids to Revelations: The Dark Turn in Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs’ Saga

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBaltimore’s Key Bridge Struck by Ship, Collapses into Water

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024