Activism

The St. Augustine Movement (1963–1964)

Hundreds of students from northern colleges recruited by the SCLC participated in demonstrations and sit-ins during Easter week of 1964. Most were jailed. “Some were made to stand in a cramped outdoor overflow pen in the late spring heat, while others were put into a concrete sweatbox overnight.”

By Tamara Shiloh

It was the spring of 1964. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference were preparing to launch a campaign to end racial discrimination in St. Augustine, Fla. King hoped that the “demonstrations there would lead to local desegregation and that media attention would garner national support for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was then stalled in a congressional filibuster,” according to Stanford University’s King Encyclopedia.

A sit-in protest at a local Woolworth’s lunch counter that ended in the arrest and imprisonment of 16 Black protestors and seven juveniles sparked the pickets. Four of the arrested, JoeAnn Anderson, Audrey Nell Edwards, Willie Carl Singleton, and Samuel White were sent to reform school for six months. No effort was made to release them until their case was publicized by Jackie Robinson, the NAACP, and the Pittsburgh Courier. They were later dubbed “the St. Augustine Four.”

It was Robert B. Hayling, advisor to the Youth Council of the city’s branch of the NAACP, who led these demonstrations. Protesters were met with violence as the Ku Klux Klan responded to their presence. Hayling and three other NAACP members were severely beaten at a 1963 Klan rally. They were arrested and convicted of assaulting their attackers.

The NAACP asked for Hayling’s resignation, but not before reaching out to the SCLC for support.

Hundreds of students from northern colleges recruited by the SCLC participated in demonstrations and sit-ins during Easter week of 1964. Most were jailed. “Some were made to stand in a cramped outdoor overflow pen in the late spring heat, while others were put into a concrete sweatbox overnight.”

When King visited St. Augustine that May, the house the SCLC rented for him was “sprayed by gunfire.” The day after the Senate voted to end the filibuster of the Civil Rights Act, King, Ralph Abernathy, and several others were arrested when they requested service at a segregated restaurant. Meanwhile, despite the violence, the SCLC continued to lead marches.

On June 18, a Grand Jury pressured King and the SCLC to leave St. Augustine for one month. The so-called goal was to “diffuse the situation, claiming that they had disrupted racial harmony in the city.”

King responded that the request was “an immoral one, as it asked the Negro community to give all, and the white community to give nothing . . . St. Augustine never had peaceful race relations.”

As the Senate debated the Civil Rights Act, SCLC lawyers began to win court victories in St. Augustine. The SCLC was encouraged to bring cases against the Klan. On July 2, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, the most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, into law.

Blacks in St. Augustine continued to face violence, intimidation, and threats, as healing took its time.

Help young readers understand the struggle for equality and a time when American laws were unfair to Blacks. Share with them Shadae Mallory’s “The History of the Civil Rights Movement: A History Book for New Readers.” Purchase at https://www.multiculturalbookstore.com

Sources: https://www.britannica.com/event/American-civil-rights-movement

https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounder/civil-rights-movement

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Schools Honor Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties

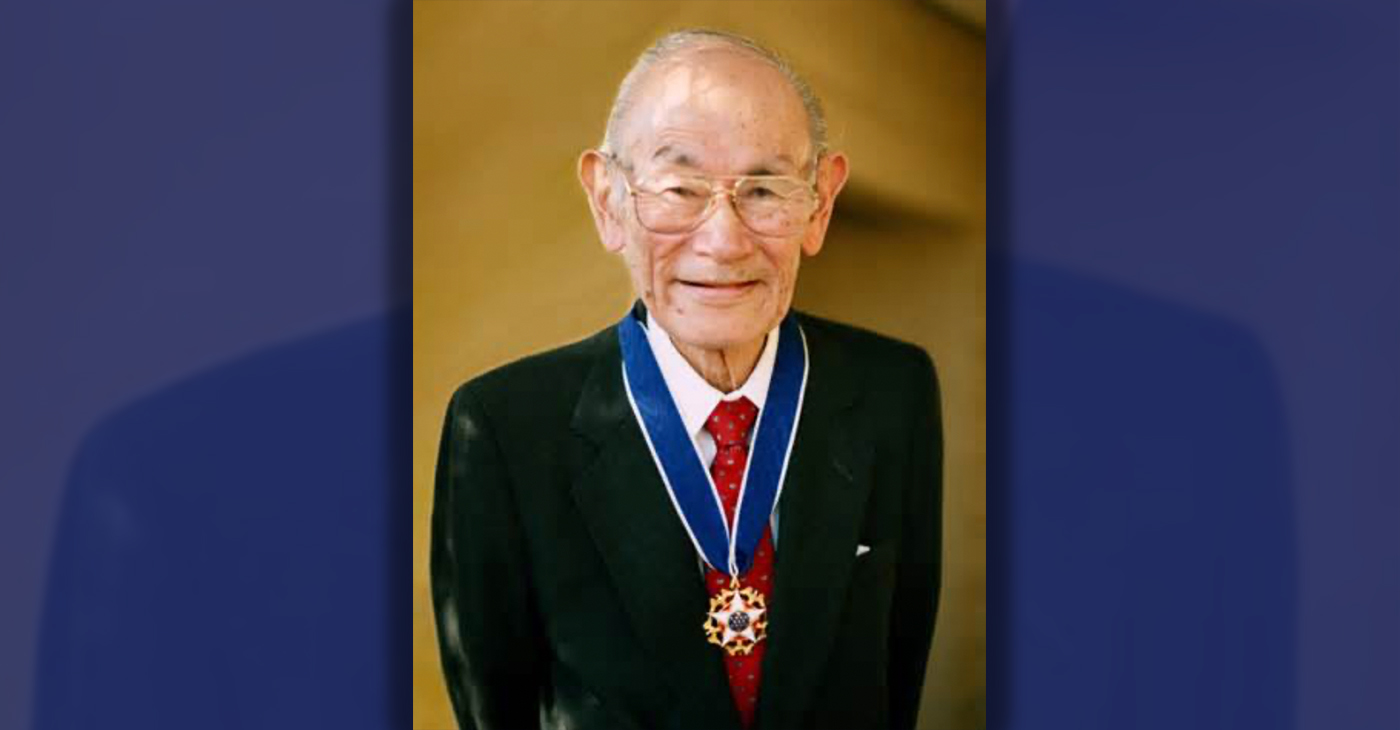

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice. His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

By Post Staff

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice.

His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

One OUSD school is named in his honor: Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy (KDA) elementary in East Oakland.

Several years ago, founding KDA Principal Charles Wilson, in a video interview with anti-hate organization “Not In Our Town,” said, “We chose the name Fred Korematsu because we really felt like the attributes that he showed in his work are things that the children need to learn … that common people can stand up and make differences in a large number of people’s lives.”

Fred Korematsu was born in Oakland on Jan. 30, 1919. His parents ran a floral nursery business, and his upbringing in Oakland shaped his worldview. His belief in the importance of standing up for your rights and the rights of others, regardless of race or background, was the foundation for his activism against racial prejudice and for the rights of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the start of the war, Korematsu was turned away from enlisting in the National Guard and the Coast Guard because of his race. He trained as a welder, working at the docks in Oakland, but was fired after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Fear and prejudice led to federal Executive Order 9066, which forced more than 120,000 Japanese Americans out of their homes and neighborhoods and into remote internment camps.

The 23-year-old Korematsu resisted the order. He underwent cosmetic surgery and assumed a false identity, choosing freedom over unjust imprisonment. His later arrest and conviction sparked a legal battle that would challenge the foundation of civil liberties in America.

Korematsu’s fight culminated in the Supreme Court’s initial ruling against him in 1944. He spent years in a Utah internment camp with his family, followed by time living in Salt Lake City where he was dogged by racism.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford overturned Executive Order 9066. Seven years later, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco vacated Korematsu’s conviction. He said in court, “I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong and do something about it so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color.”

Korematsu’s dedication and determination established him as a national icon of civil rights and social justice. He advocated for justice with Rosa Parks. In 1998, President Bill Clinton gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom saying, “In the long history of our country’s constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls … To that distinguished list, today we add the name of Fred Korematsu.”

After Sept. 11, 2001, Korematsu spoke out against hatred and discrimination, saying what happened to Japanese Americans should not happen to people of Middle Eastern descent.

Korematsu’s roots in Oakland and his education in OUSD are a source of great pride for the city, according to the school district. His most famous quote, which is on the Korematsu elementary school mural, is as relevant now as ever, “If you have the feeling that something is wrong, don’t be afraid to speak up.”

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoAG Bonta Says Oakland School Leaders Should Comply with State Laws to Avoid ‘Disparate Harm’ When Closing or Merging Schools

-

Community7 days ago

Community7 days agoOakland WNBA Player to be Inducted Into Hall of Fame