Business

Some Upbeat News for Black Businesses Still Reeling From Pandemic Losses

During a news briefing hosted by Ethnic Media Services last month, speakers discussed how small businesses in California and around the country can emerge from this crisis, catch the wave of what seems to be a gathering economic boom, or continue to tread water to stay afloat.

Next week, after more than a year, California is expected to lift the majority of its COVID-19 related restrictions and reopen its economy at almost-full capacity.

But as the state prepares for a long-anticipated comeback, many Black business-owners say enterprises across the state that African Americans own face an uphill road to recovery.

“It’s a state of disrepair. They need significant support,” said Tara Lynn Gray, director of the California Office of the Small Business Advocate.

Black-owned business operators who are struggling will need all the financial support available to them, Gray told California Black Media (CBM) at a luncheon hosted by the California Black Chamber of Commerce in Sacramento.

(Black businesses) have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19,” Gray said. “Fortunately, the governor has stepped up and provided $2.5 billion dollars in relief funds to all small businesses with priority to the disadvantaged communities of color.”

In February 2020, there were 1 million Black-owned businesses in operation around the United States, according to a University of California at Santa Cruz report.

About six weeks later, after the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the number of Black business owners had dropped to 440,000, a 41%, reduction. Many of them had to shut down their businesses for good.

During the same time, only 17% of white proprietors had to shut down their businesses, UC Santa Cruz research shows. Overall, nearly 4 million minority-owned U.S. firms, whose annual sales total close to $700 billion, shuttered because of COVID-19.

But despite the grim statistics, a number of small business advocates say there is financial help available both at the state and federal levels for most business-owners.

During a news briefing hosted by Ethnic Media Services last month, speakers discussed how small businesses in California and around the country can emerge from this crisis, catch the wave of what seems to be a gathering economic boom, or continue to tread water to stay afloat.

The main objective of the briefing was helping small businesses, particularly minority owned ones, connect to various sources of funding created to help them recover from the pandemic.

The key is to apply for the money, said Everett Sands, CEO of Lendistry, a leading, Black-led Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) and Community Development Entity (CDE) that is also a small business and commercial real estate lender.

“Let’s make an assumption. If you are allowed to open, and you can open, then therefore you should be able to receive some type of revenue,” Sands said. “What we’ve learned about the pandemic is that most opportunities are coming a second time. If you look at the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), it came a third time. But it is important for businesses to apply.”

The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) is a federal revenue replacement program designed to sustain small business jobs during the ongoing public health and economic crisis. May 31 was the last day for small business owners operating in low-income neighborhoods to apply for the third round of PPP loans.

In California, Lendistry helped thousands of small businesses secure loans and grants during the pandemic. Funded by the State of California through the California Office of the Small Business Advocate, Lendistry, was the state-contracted administrator of the program that administered six rounds of grant funding for non-profits and underserved businesses.

Sands was one of the guest speakers along with U.S. Congressman Ro Khanna (D-CA-17), a member of the Congressional Small Business Caucus, and Virginia Ali. Ali owns the nationally renowned restaurant and Black-owned small business Ben’s Chili Bowl in Wash., D.C.

Sands said before the virus surfaced, minority businesses were already in a “financially precarious position” with strained resources. Small businesses had limited access to capital, he said, and they lacked the infrastructure to apply for loans or contracts and many of them couldn’t self-finance in the long term.

But on the cusp of the state and U.S. economies reopening, Sands says it is not too late for businesses to get their financial footing.

“As a result of the American Rescue Plan, most states received roughly $1 billion to help these small businesses increase their revenues” he said.

Of California’s 4.1 million small businesses, 1.2 million (29%) are minority-owned. ZIPPIA, an online career support company, calculated that 10,287 Black-owned businesses operate in California. According to the June 2020 report by ZIPPIA, titled the “Most Supportive States for Black Businesses,” California ranked No. 4 before the pandemic. Based on data compiled by the United States Census’ Annual Business Survey, California’s Black businesses employ roughly 81,530 people.

Gray said restaurants, barbershops, nail salons, hair salons, hospitality, and personal grooming services have been “inexplicably hurt” due to social-distancing restrictions in the state.

Those businesses, owned by many African Americans, were not deemed as essential when a shelter-in-place order was mandated. Now those are the businesses that Newsom intends to help, Gray stated.

“Our governor had a tough choice to make,” Gray said. “You close things down to make sure people are safe. Public health is a serious issue. I applaud him for doing that. Yes, there are consequences to our small businesses. But in the end, look at us now. We have the lowest positivity rate in the nation. Also, it looks like our economy is coming back.”

A survey conducted by H&R Block found that out of 3,000 small businesses, 53% of Black business operators saw their revenues cut in half due to the pandemic as compared to 37% of White owners.

Black-owned small businesses continue to experience disproportionate difficulties, with 35% of Black entrepreneurs reporting that business conditions are worsening. Many say they may not survive the next three months.

While the reopening of the economy signals progress, Sands is encouraging Black businesses to pay attention to Small Business Administration programs (SBA) that include loans, a restaurant relief fund and venture capital investments.

To apply for federal small business funding, Sands says, a company only has to show the sole business’ gross revenue. Applicants won’t be excluded if the proprietor has been a borrower on a defaulted student loan or has a criminal history.

“For amounts less than $150,000, most of the red tape or the bureaucratic process of a loan has been cleared away,” Sands said.

Khanna said more funding is expected to be distributed through the Saving Our Street Act, which would allocate loans of up to $250,000 to businesses with fewer than 10 employees.

Distribution of the money will be based on the racial and gender diversity of the business owners, he said, and it should help the economy get stronger and financially stabilize the country.

“In this next quarter, we’re going to have a pretty good recovery,” he said. “Consumer spending is at 10% growth. I think small businesses are going to come back strong. The problem is a lot of businesses that have had to close may not be able to reopen. And that’s where we have to focus: assisting with debt forgiveness and capital for those businesses that would not survive.”

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Bay Area

State Controller Malia Cohen Keynote Speaker at S.F. Wealth Conference

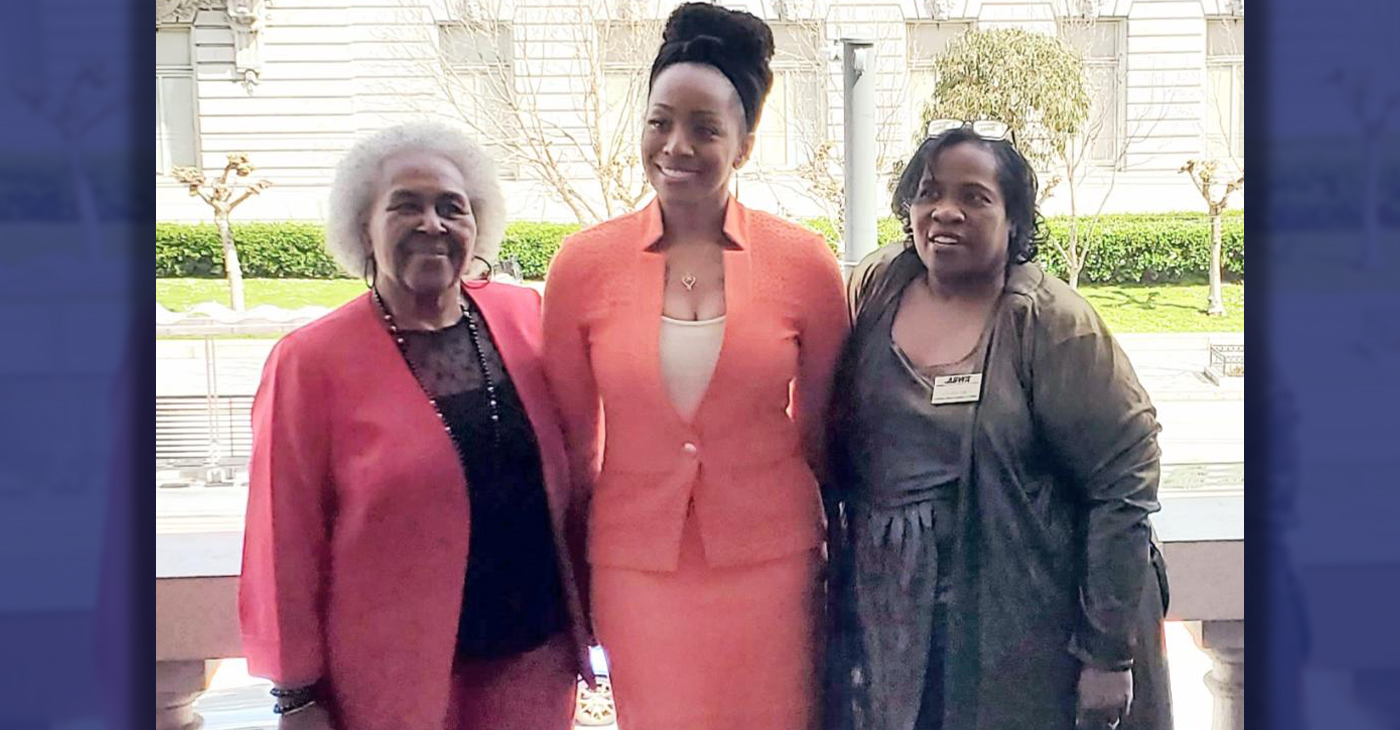

California State Controller Malia Cohen delivered the keynote speech to over 50 business women at the Black Wealth Brunch held on March 28 at the War Memorial and Performing Arts Center at 301 Van Ness Ave. in San Francisco. The Enterprising Women Networking SF Chapter of the American Business Women’s Association (ABWA) hosted the Green Room event to launch its platform designed to close the racial wealth gap in Black and Brown communities.

By Carla Thomas

California State Controller Malia Cohen delivered the keynote speech to over 50 business women at the Black Wealth Brunch held on March 28 at the War Memorial and Performing Arts Center at 301 Van Ness Ave. in San Francisco.

The Enterprising Women Networking SF Chapter of the American Business Women’s Association (ABWA) hosted the Green Room event to launch its platform designed to close the racial wealth gap in Black and Brown communities.

“Our goal is to educate Black and Brown families in the masses about financial wellness, wealth building, and how to protect and preserve wealth,” said ABWA San Francisco Chapter President LaRonda Smith.

ABWA’s mission is to bring together businesswomen of diverse occupations and provide opportunities for them to help themselves and others grow personally and professionally through leadership, education, networking support, and national recognition.

“This day is about recognizing influential women, hearing from an accomplished woman as our keynote speaker and allowing women to come together as powerful people,” said ABWA SF Chapter Vice President Velma Landers.

More than 60 attendees dined on the culinary delights of Chef Sharon Lee of The Spot catering, which included a full soul food brunch of skewered shrimp, chicken, blackened salmon, and mac and cheese.

Cohen discussed the many economic disparities women and people of color face. From pay equity to financial literacy, Cohen shared not only statistics, but was excited about a new solution in motion which entailed partnering with Californians for Financial Education.

“I want everyone to reach their full potential,” she said. “Just a few weeks ago in Sacramento, I partnered with an organization, Californians for Financial Education.

“We gathered 990 signatures and submitted it to the [California] Secretary of State to get an initiative on the ballot that guarantees personal finance courses for every public school kid in the state of California.

“Every California student deserves an equal opportunity to learn about filing taxes, interest rates, budgets, and understanding the impact of credit scores. The way we begin to do that is to teach it,” Cohen said.

By equipping students with information, Cohen hopes to close the financial wealth gap, and give everyone an opportunity to reach their full financial potential. “They have to first be equipped with the information and education is the key. Then all we need are opportunities to step into spaces and places of power.”

Cohen went on to share that in her own upbringing, she was not guided on financial principles that could jump start her finances. “Communities of color don’t have the same information and I don’t know about you, but I did not grow up listening to my parents discussing their assets, their investments, and diversifying their portfolio. This is the kind of nomenclature and language we are trying to introduce to our future generations so we can pivot from a life of poverty so we can pivot away and never return to poverty.”

Cohen urged audience members to pass the initiative on the November 2024 ballot.

“When we come together as women, uplift women, and support women, we all win. By networking and learning together, we can continue to build generational wealth,” said Landers. “Passing a powerful initiative will ensure the next generation of California students will be empowered to make more informed financial decisions, decisions that will last them a lifetime.”

Business

Black Business Summit Focuses on Equity, Access and Data

The California African American Chamber of Commerce hosted its second annual “State of the California African American Economy Summit,” with the aim of bolstering Black economic influence through education and fellowship. Held Jan. 24 to Jan. 25 at the Westin Los Angeles Airport Hotel, the convention brought together some of the most influential Black business leaders, policy makers and economic thinkers in the state. The discussions focused on a wide range of economic topics pertinent to California’s African American business community, including policy, government contracts, and equity, and more.

By Solomon O. Smith, California Black Media

The California African American Chamber of Commerce hosted its second annual “State of the California African American Economy Summit,” with the aim of bolstering Black economic influence through education and fellowship.

Held Jan. 24 to Jan. 25 at the Westin Los Angeles Airport Hotel, the convention brought together some of the most influential Black business leaders, policy makers and economic thinkers in the state. The discussions focused on a wide range of economic topics pertinent to California’s African American business community, including policy, government contracts, and equity, and more.

Toks Omishakin, Secretary of the California State Transportation Agency (CALSTA) was a guest at the event. He told attendees about his department’s efforts to increase access for Black business owners.

“One thing I’m taking away from this for sure is we’re going to have to do a better job of connecting through your chambers of all these opportunities of billions of dollars that are coming down the pike. I’m honestly disappointed that people don’t know, so we’ll do better,” said Omishakin.

Lueathel Seawood, the president of the African American Chamber of Commerce of San Joaquin County, expressed frustration with obtaining federal contracts for small businesses, and completing the process. She observed that once a small business was certified as DBE, a Disadvantaged Business Enterprises, there was little help getting to the next step.

Omishakin admitted there is more work to be done to help them complete the process and include them in upcoming projects. However, the high-speed rail system expansion by the California High-Speed Rail Authority has set a goal of 30% participation from small businesses — only 10 percent is set aside for DBE.

The importance of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) in economics was reinforced during the “State of the California Economy” talk led by author and economist Julianne Malveaux, and Anthony Asadullah Samad, Executive Director of the Mervyn Dymally African American Political and Economic Institute (MDAAPEI) at California State University, Dominguez Hills.

Assaults on DEI disproportionately affect women of color and Black women, according to Malveaux. When asked what role the loss of DEI might serve in economics, she suggested a more sinister purpose.

“The genesis of all this is anti-blackness. So, your question about how this fits into the economy is economic exclusion, that essentially has been promoted as public policy,” said Malveaux.

The most anticipated speaker at the event was Janice Bryant Howroyd known affectionately to her peers as “JBH.” She is one of the first Black women to run and own a multi-billion-dollar company. Her company ActOne Group, is one of the largest, and most recognized, hiring, staffing and human resources firms in the world. She is the author of “Acting Up” and has a profile on Forbes.

Chairman of the board of directors of the California African American Chamber of Commerce, Timothy Alan Simon, a lawyer and the first Black Appointments Secretary in the Office of the Governor of California, moderated. They discussed the state of Black entrepreneurship in the country and Howroyd gave advice to other business owners.

“We look to inspire and educate,” said Howroyd. “Inspiration is great but when I’ve got people’s attention, I want to teach them something.”

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoAG Bonta Says Oakland School Leaders Should Comply with State Laws to Avoid ‘Disparate Harm’ When Closing or Merging Schools

-

Community7 days ago

Community7 days agoOakland WNBA Player to be Inducted Into Hall of Fame