Art

Q&A: Matt Takaichi’s Sardonic Tech Work Photography

In 2014, East Bay artist Matt Takaichi was taking photos mostly on the street, but he soon started using this process-based approach for a project that would become “Developers,” his recently published first photography book of work from 2015-2020. To make the book, he went to over 50 Bay Area tech conferences, often by sneaking in, and took well over 10,000 photos that captured tech work in sad and funny ways.

By Zack Haber

In an interview from 2014, East Bay artist Matt Takaichi shied away from claiming he had a special eye for taking photos and instead said his ability to capture compelling images stems from “the extent” he takes to “position” himself for them. At that point, Takaichi was taking photos mostly on the street, but he soon started using this process-based approach for a project that would become “Developers,” his recently published first photography book of work from 2015-2020. To make the book, he went to over 50 Bay Area tech conferences, often by sneaking in, and took well over 10,000 photos that captured tech work in sad and funny ways.

While working on the project, Takaichi became obsessed and had trouble fathoming how it could end. But shelter-in-place hit in March of 2020, and the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered these in-person events, making it impossible for him to continue photographing them. He then began a year-long editing process and collaborated with Oakland-based book designer Kate Robinson to organize and self-publish “Developers,” selecting about 120 of these photos, most of which appear in black and white. Readers can purchase the book using this link. Takaichi discusses his book in the following interview, which I’ve edited for brevity and clarity.

Zack Haber: Why did you make a book about tech conferences? The book starts out showing protests. Was there anything political you wanted to explore?

Matt Takaichi: I’d been doing street photography for a while before I had the idea for this book. I was on the streets taking photos of people out and about. As I tried to put those photos together and figure out some way they made sense, I started to feel I needed to do a project that was a little more grounded and had some criticism or point to it.

I had the idea to do this project when I was thinking about how my Mom was a meeting planner for a tech company. Her job was to organize tech conferences. When I was living at home with her, there was one event where she hired me to photograph people as they were receiving awards. I remember thinking at the time ‘this is really stupid, this isn’t the type of photography I want to do.’ I was being kind of bratty. Then I thought about that later and I was like, oh, that could have been really interesting if I had approached it a little bit differently.

Photo by Matt Takaichi from his book, Developers, which captures Bay Area tech conferences from 2015-2020 and was released in late 2021.

Around this time too, while living in the Bay Area, I was thinking about the economy here and how much of it is centered around tech. It seemed like a pretty straight shot if I did something around photographing tech, but I was also thinking about how I could bring street photography into that. But I couldn’t just walk into Google and start taking photos of people.

Then I thought about going into tech conferences. I had a sense of them while growing up and walked past them a lot in San Francisco. That’s really the only place tech congregates in a somewhat visible public way. It seemed like the only option where you could do a documentary style street photo type of a tech project and be around people to get their natural reactions. I thought ‘Here’s the biggest target and here’s the only way I can conceive of doing it.’ When I started I don’t think I had a real idea of what I was doing. It was just that concept and wanting to do it in a way that could be critical and funny.

Photo by Matt Takaichi from his book, Developers, which captures Bay Area tech conferences from 2015-2020 and was released in late 2021.

I think especially at the time, 2015, there was a lot of antagonism toward tech. People were blocking Google buses. The anti-techie thing was really proliferating. I wanted to do some photos about how people perceived tech and the power centered around it and the wealth. But then when I was making the photos, I started realizing there was a lot of resentment among the workers, too. People didn’t want to be there. There was a lot of fatigue. As I did more of the project, things started to get really interesting in Bay Area organizing circles. I got really into this group called the Tech Workers Coalition. I thought a lot of their ideas for organizing were really interesting. For them, tech labor organizing should encompass everyone in the industry, not just engineers. There’s people servicing the tech industry, like cooks, and people in all sorts of lower paid positions. To me they all qualify as tech workers. At these events that service work was everywhere. And those workers made it into my book.

Unionizing in tech work was also entering into the popular consciousness more in the Bay Area. It was something I hadn’t really seen before. Now there’s the Alphabet Workers Union at Google, for example. At the same time, being someone who was employed in the industry before, I noticed those types of organizing hadn’t really penetrated the workforce as much as I’d like them to. It wasn’t common and still isn’t.

Photo by Matt Takaichi from his book, Developers, which captures Bay Area tech conferences from 2015-2020 and was released in late 2021.

A lot of political photographs I had were labor protests by service workers that took place right outside the tech conventions. I have one that’s the Marriott strikers and they made flyers that were specific to people attending a tech conference. You see from the images there’s not a whole lot of interest from tech workers to engage with that. That’s what I’ve seen in the tech industry. You have workers who are pretty unhappy and are working long hours. At the same time there’s not really an infrastructure around collective bargaining to make the workplace better. But from my images you can see that there might be a latent desire to do that, if it could surface in a way that was a bit more legible to them. Who knows? There could be something there.

Can you talk a little bit about sneaking into these conferences, and what that felt like?

Takaichi: When I started doing this, I’d had the idea for a while but wasn’t sure how I’d execute it. Then one day I was walking around downtown San Francisco and saw the Moscone Center was having a tech conference. On a whim I was just like, let’s go for it. I walked into the building, went up the escalator, entered with a group of people and the security guard didn’t really register me.

That was the first event I snuck into. The security guard came up to me once and was like, ‘oh, hey, where’s your badge?’ Then I mumbled something incoherent and acted like I knew what I was doing, and he was like ‘oh OK, you’re good.’

Based on that first experience, I realized it wasn’t hard and I could just keep doing that going forward. Soon I stopped impulsively going to tech conferences. Instead, I learned about how they were scheduled and that, for about half of them, I could register and enter in for free. Most of the photos from the book though are from ones I snuck into. Sometimes, I could have paid to go to those events but it would have been like $400, which was way too expensive for me.

Subconsciously I always felt like I shouldn’t be there. I worried a little bit that people would find out I was working on this project. But before long though, I realized it was pretty low stakes. The worst thing that could happen is that I’d have been asked to leave. It wouldn’t have been a big deal.

Of course, I preferred not to get caught. But that never really happened. A lot of people just thought I was an event photographer. That was something I kind of had to learn how to navigate at first. Sometimes someone I wasn’t interacting with at first would be like ‘oh cool, take my photo.’

Eventually I just started telling people exactly what my project was when they asked, that I was working on a documentary series of images you might not normally see at a tech conference that showed how it wasn’t always fun. Almost all of them thought it was a good idea and they were often really cordial with me. One time I saw one of these people at a bar months later and he started going on this long rant about different ways he thought I could make a lot of money from my photos, which I thought was really funny.

I counted about 15 photos in “Developers” where people appear to stare directly at you or into the camera. Most, but not all, of these people look perturbed, annoyed, and perhaps suspicious of what you’re doing. I love these photos. They make me feel both unsettled and fascinated. There’s a taboo being broken here. As a child I remember being told not to stare at strangers. Why break that taboo? What did it feel like taking these photos?

To me these questions get at a lot of larger questions around street photography and what it’s like taking photos of people on the street who may not always know I’m doing that. I really struggled with how I felt about that for a while. I’ve been really into a lot of classic Magnum photographers, people like Josef Koudelka. What I really like about their photos is you’re just getting this slice of reality from 50 or 60 years ago. Everything feels really genuine, like it wasn’t posed.

It’s really hard to do that if someone knows you’re about to take their photo. I think to some extent it’s not cool to take those photos. At the same time, street photography has become part of the art canon. People like Henri Cartier-Bresson are seen as great artists of the 20th century. It’s kind of validated doing this type of photography.

All this is to say I never really figured out a way to navigate doing it. But what I will say about this project, and why I don’t feel as weird about doing it as I did about other street photography, is that there’s something about entering into the space of a tech conference that makes people assume you belong there. It’s different from taking photos on the street. Once you’re in a tech conference, there’s an assumption that everyone there is in a segment of workers basically, where maybe you’re all coming from a university background. And there’s security making sure everyone who goes in fits a profile. Due to that I think people drop their guard down pretty significantly.

Also in tech conferences, tons of people are running around with cameras. Some of them are working to boost their companies. There’s this tacit agreement that people there are being presenters speaking on behalf of a company. They’re there to advertise. On the one hand it’s a private space, but people are really putting themselves out there.

Honestly, in photos I have where someone has a weird facial expression, I wasn’t too sure they were even looking at me. These places were so dense with people. I use a pretty wide-angle lens and have a pretty discrete setup. When people looked a little frustrated sometimes, I would quickly snap my photo, especially because people’s facial expressions change so quickly.

I felt a little bit free from having to be super conscious of how I was being perceived all the time. A huge part of street photography is knowing how you appear to other people, because that’s going to inform how they react to you, which will change how they appear. You can smile at someone in the street and sometimes you’ll get this nice reception from them for a photo. But with this project I felt like I could really just be a fly on the wall. People weren’t paying much attention to me.

Your photos show an absurdity that’s often comical but also has a deep sadness. There’s lots of photos of people clearly stressed and/or exhausted while others show a strange carnivalesque showmanship and excitement. It makes me wonder: What was it like being in that space? What did you learn about these people and what tech work does to them?

When I saw people at the booths kind of doing their whole song and dance, it showed how when you’re employed in these jobs, you have to try to convince people that the company you work for is great. You have to keep inside whatever you feel about working there and just put your best face forward. I think there’s just something inherently conflictual about doing that. Needing to give this really positive facing image of your company really wears you down. You feel like you’re doing something that isn’t reflective of how you really feel and what it’s actually like to work there. Your coworkers are doing the same thing but when you look around it seems like they’re happy.

I don’t think people are happy working 80-hour weeks, which is pretty common in the tech industry. I think a lot of people feel bad about it. I wanted to have a lot of shots of the frontward facing image of what tech looks like and then ones where you kind of take a step back after people are done presenting and the fatigue shows up. People are just sitting on the ground looking exhausted. They’re calling their family and wishing they were there instead.

I think there’s a point in a lot of people’s adult life where you kind of just realize ‘I’m going to have to work and do these things I don’t like to do.’ Especially in this context of where the US is at right now, there’s not a whole lot of ways for most people to have any say as to what their company produces and how they’re managed.

Being in these tech conferences, it really was just like a show of force. You feel like you’re coming into something that’s powerful and disciplining to workers. It’s a little overwhelming realizing what people are up against now.

Art

Marin County: A Snapshot of California’s Black History Is on Display

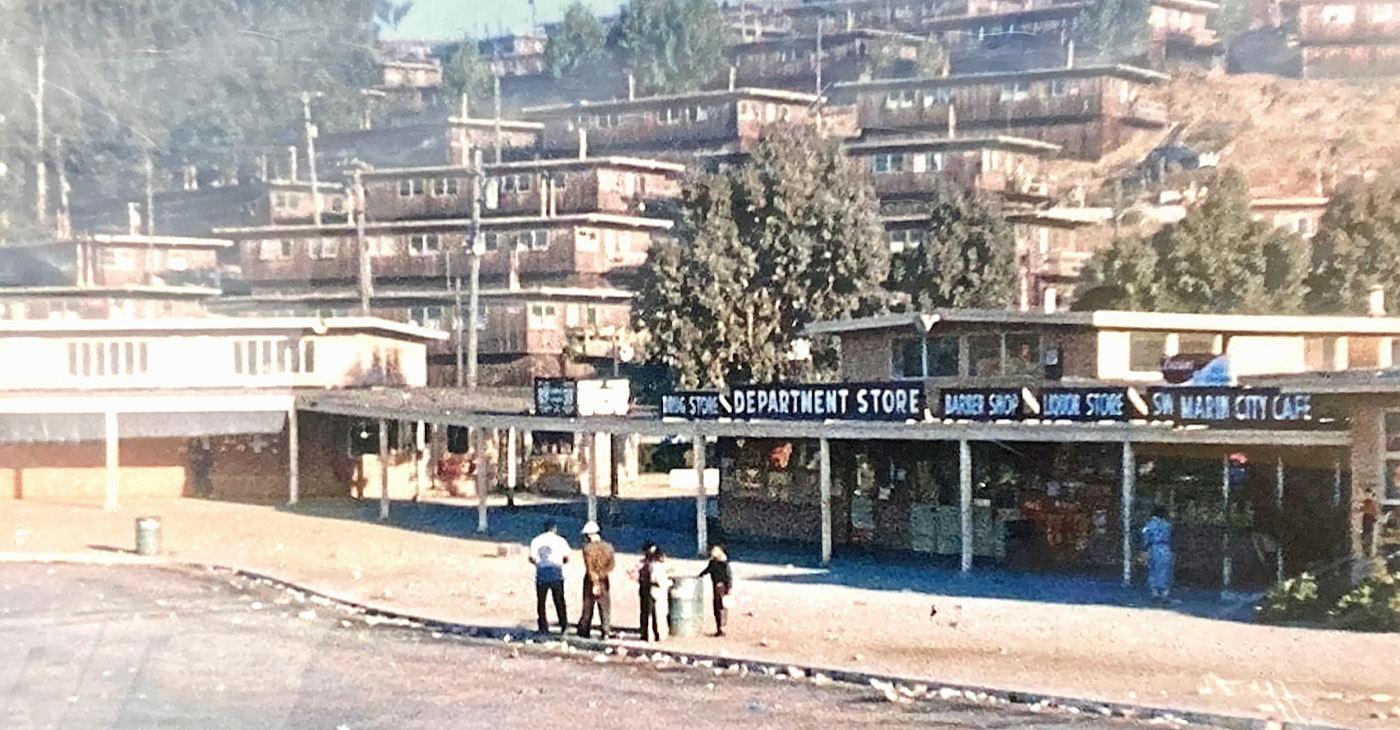

The Marin County Office of Education, located at 1111 Las Gallinas Ave in San Rafael, will host the extraordinary exhibit, “The Legacy of Marin City: A California Black History Story (1942-1960),” from Feb. 1 to May 31, 2024. The interactive, historical, and immersive exhibit featuring memorabilia from Black shipyard workers who migrated from the South to the West Coast to work at the Marinship shipyard will provide an enriching experience for students and school staff. Community organizations will also be invited to tour the exhibit.

By Post Staff

The Marin County Office of Education, located at 1111 Las Gallinas Ave in San Rafael, will host the extraordinary exhibit, “The Legacy of Marin City: A California Black History Story (1942-1960),” from Feb. 1 to May 31, 2024.

The interactive, historical, and immersive exhibit featuring memorabilia from Black shipyard workers who migrated from the South to the West Coast to work at the Marinship shipyard will provide an enriching experience for students and school staff. Community organizations will also be invited to tour the exhibit.

All will have the opportunity to visit and be guided by its curator Felecia Gaston.

The exhibit will include photographs, articles and artifacts about the Black experience in Marin City from 1942 to 1960 from the Felecia Gaston Collection, the Anne T. Kent California Room Collection, The Ruth Marion and Pirkle Jones Collection, The Bancroft Library, and the Daniel Ruark Collection.

It also features contemporary original artwork by Chuck D of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame group Public Enemy, clay sculptures by San Francisco-based artist Kaytea Petro, and art pieces made by Marin City youth in collaboration with Lynn Sondag, Associate Professor of Art at Dominican University of California.

The exhibit explores how Marin City residents endured housing inequities over the years and captures the history of plans to remove Black residents from the area after World War II. Throughout, it embodies the spirit of survival and endurance that emboldened the people who made Marin City home.

Felecia Gaston is the author of the commemorative book, ‘A Brand New Start…This is Home: The Story of World War II Marinship and the Legacy of Marin City.’ Thanks to the generous contribution of benefactors, a set of Felecia’s book will be placed in every public elementary, middle, and high school library in Marin.

In addition, educators and librarians at each school will have the opportunity to engage with Felecia in a review of best practices for utilizing the valuable primary sources within the book.

“Our goal is to provide students with the opportunity to learn from these significant and historical contributions to Marin County, California, and the United States,” said John Carroll, Marin County Superintendent of Schools.

“By engaging with Felecia’s book and then visiting the exhibit, students will be able to further connect their knowledge and gain a deeper understanding of this significant historical period,” Carroll continued.

Felecia Gaston adds, “The Marin County Office of Education’s decision to bring the Marin City Historical Traveling Exhibit and publication, ‘A Brand New Start…This is Home’ to young students is intentional and plays a substantial role in the educational world. It is imperative that our community knows the contributions of Marin City Black residents to Marin County. Our youth are best placed to lead this transformation.”

The Marin County Office of Education will host an Open House Reception of the exhibit’s debut on Feb. 1 from 4 p.m. – 6 p.m.. All school staff, educators, librarians, and community members are encouraged to attend to preview the exhibit and connect with Felecia Gaston. To contact Gaston, email MarinCityLegacy@marinschools.org

Activism

Alternative Outcome to Slayings by Police Explored in One-Man Play

BLACK MEN EVERYWHERE! is the explosive new one man play written, directed, and performed by Jinho “Piper” Ferreira. Set against the backdrop of a presidential election, the play explores how political and cultural leaders wield the myth of the dangerous Black man to manipulate the masses for personal gain. Piper penned the follow-up to his ground-breaking solo play, “Cops and Robbers,” after an impromptu cross-country Black history tour.

Special to The Post

What would happen if police officers who have gotten off for killing unarmed Black people started turning up dead?

BLACK MEN EVERYWHERE! is the explosive new one man play written, directed, and performed by Jinho “Piper” Ferreira. Set against the backdrop of a presidential election, the play explores how political and cultural leaders wield the myth of the dangerous Black man to manipulate the masses for personal gain.

Piper penned the follow-up to his ground-breaking solo play, “Cops and Robbers,” after an impromptu cross-country Black history tour.

“My wife and I had been talking about it for years,” Ferreira said. They had taken their three children to Brazil several times and West Africa but had yet to explore their history as Black people in this country. “It was Juneteenth last year and I realized we had a few weeks to make it happen, so we just jumped in the car and left” Piper said.

Three weeks later the family had seen everything from the African American Museum of History and Culture in Wash., D.C., to the phenomenally preserved Whitney Plantation in Louisiana. They’d stood outside of the balcony of the Lorraine Hotel where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn., walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., and paid their respects at the Africa Town cemetery – where the passengers of the Clotilda (the last known U.S. slave ship to smuggle captured Africans into this country) were buried near Mobile, Ala.

“We had the kids keep a journal of the trip and my wife and I took notes, but once we got back home, I knew I had to make the pen move,” he said.

Ferreira plays 21 characters in the 60-minute emotional roller coaster ride; personalities we all know. While brilliantly weaving in themes of revolution, treachery, and revenge, “Black Men Everywhere!” is surprisingly — more than anything else — a love story.

“I wrote the play for Black men and everyone who loves us,” Ferreira said. “The play is narrated by a sistah and performed in front of the deeply spiritual artwork of Nedra T. Williams, an Oakland priestess of Olokun. It’s called ‘Black Men Everywhere!’ but we don’t exist without the Black woman.”

For tickets, please go to: http://tinyurl.com/5dm3mhra

Art

City of Stockton Seeks Applications for Public Art Murals

The City of Stockton Arts Commission (SAC) has announced the opportunity for artist(s) and/or artist teams to apply to design and paint original artwork on City-owned property through a Public Art Mural Program. The deadline for applications is Friday, March 8, 2024, at 5 p.m. Applications and additional information are available online at www.stocktonca.gov/publicart.

City of Stockton

The City of Stockton Arts Commission (SAC) has announced the opportunity for artist(s) and/or artist teams to apply to design and paint original artwork on City-owned property through a Public Art Mural Program.

The deadline for applications is Friday, March 8, 2024, at 5 p.m. Applications and additional information are available online at www.stocktonca.gov/publicart.

The Public Art Mural Program incentivizes mural installations by providing city funding and the means of curating the City’s collection of murals.

This program has $50,000 in available funds for artist(s) and is also available for those who have already identified funds and would like to complete a mural project on city-owned property. Applications will be reviewed on a competitive basis and selected by the SAC.

To learn more about the Stockton Arts Commission (SAC) or qualifications and eligibility for Public Art Mural Program, please visit www.stocktonca.gov/publicart or call the Community Services Department at (209) 937-8206.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024