Bay Area

Opinion: Coronavirus Makes it More Clear Than Ever: Health Care is a Human Right

Who is going to pay for this?

Who is going to pay for this?

For months that question was used as a weapon against supporters of Medicare for All. Now, it is on everyone’s mind as they worry about the costs of the testing and treatment for the coronavirus. The virus is highly contagious. We need everyone with symptoms to get tested and all with the virus to get treatment. If anyone hesitates because they fear they can’t afford the cost, they put the rest of us at risk.

No one should be worried about the costs of treatment.

Those costs, however, are going to be staggering, particularly if the fears of the administration’s leading expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, are realized and a million or more may become infected with the disease. Hospitalization and treatment will cost hundreds of billions. The average cost of hospitalization for pneumonia patients is about $20,000, but many coronavirus patients tend to need to stay on ventilators longer and fight off more complications than pneumonia patients.

Across the country, Americans are terrified at the potential costs if they get sick. Twenty-seven million Americans have no health insurance at all. Four in 10 working Americans have a high-deductible plan that forces them to pay thousands of dollars out of pocket before they get benefit from the premiums taken out of their paychecks each week.

A 2009 Harvard Medical School study estimated that every year an estimated 45,000 people in the U.S. die because of lack of health care coverage. Many suffer because they put off necessary treatment because they can’t afford it. Now, as Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Cal., put it, “The reality is, there are a lot of people that are thinking, ‘I don’t want a couple thousand-dollar bill to get tested or get treated.”

The rescue bill just passed by Congress covers the costs of testing. Trump promised that any cost of treatment also would be covered, but the insurance lobby immediately corrected him. Since then, under immense pressure, Cigna and Humana have joined CVS Aetna insurance in agreeing to waive patient cost-sharing on treatment for those insured.

Hopefully, this will reassure people enough that they won’t avoid getting tested and treated, posing the threat to all. But this won’t be charity. Some health-care analysts think the insurance industry could benefit from the pandemic because people generally are putting off visits to doctors and hospitals as much as possible.

In any case, insurers admit that if the costs soar they will factor it into the cost of plans next year. As Peter Lee, the head of Covered California, an independent state agency, noted, insurers are likely to seek rates next year that are double their additional costs from the virus. If costs go up 20 percent, rates could jump as much as 40 percent. That could mean, Lee warned, “many of the 170 million Americans in the commercial market may lose their coverage and go without needed care.”

The insurers will sustain their profits; it’s the patients who will suffer.

The government is investing billions of dollars to develop a vaccine for the virus, and to develop other drugs that can help treat it. Yet, because the government turns over any drug developed to the private pharmaceutical companies, Health Secretary Alex Azar — a former lobbyist for the drug companies — said he couldn’t guarantee that the treatments would be affordable. Already, as the Intercept reported, bankers are goading drug companies to prepare to raise prices to benefit from the expected demand.

The U.S. spends about twice as much per capita for its patchwork health-care system than most industrialized countries. Why were we caught with such shortages of masks, ventilators or hospital beds?

A central reason is that about $500 billion of what we spend on health care each year doesn’t go to health care. It is wasted on costly bureaucracies needed to bill the maze of private insurers or track down patients for their co-pays. It goes to hundreds of billions in profits for insurance companies and drug companies. It goes to excessive CEO salaries rising to $80 million or so a year.

In the end, the federal government will and should step up to cover the costs of all testing and treatment for the pandemic. It will have to reimburse states to cover soaring Medicaid and hospital costs. It will pay for developing the necessary drugs. It will pay for the costs of covering seniors under Medicare. It will pay for the costs incurred by those without insurance or with employer-based insurance. Yet, in part because of this, the insurance companies and drug companies will keep racking up record profits.

At this point, the overriding imperative is that every person in the U.S. understand that they should get the testing and treatment they need. All should be reassured that their costs will be covered. Congress went part of the way with the last rescue package. It should finish the job, preferably by having Medicare pay for all the costs directly.

But we shouldn’t be satisfied with single-payer coverage just during a massive pandemic. This crisis exposes dramatically the foolishness of pretending that health care is a private marketplace. Health care is a human right. This pandemic gives ample evidence of why we need to move to a Medicare for All system where high-quality health care is guaranteed to all.

Alameda County

DA Pamela Price Stands by Mom Who Lost Son to Gun Violence in Oakland

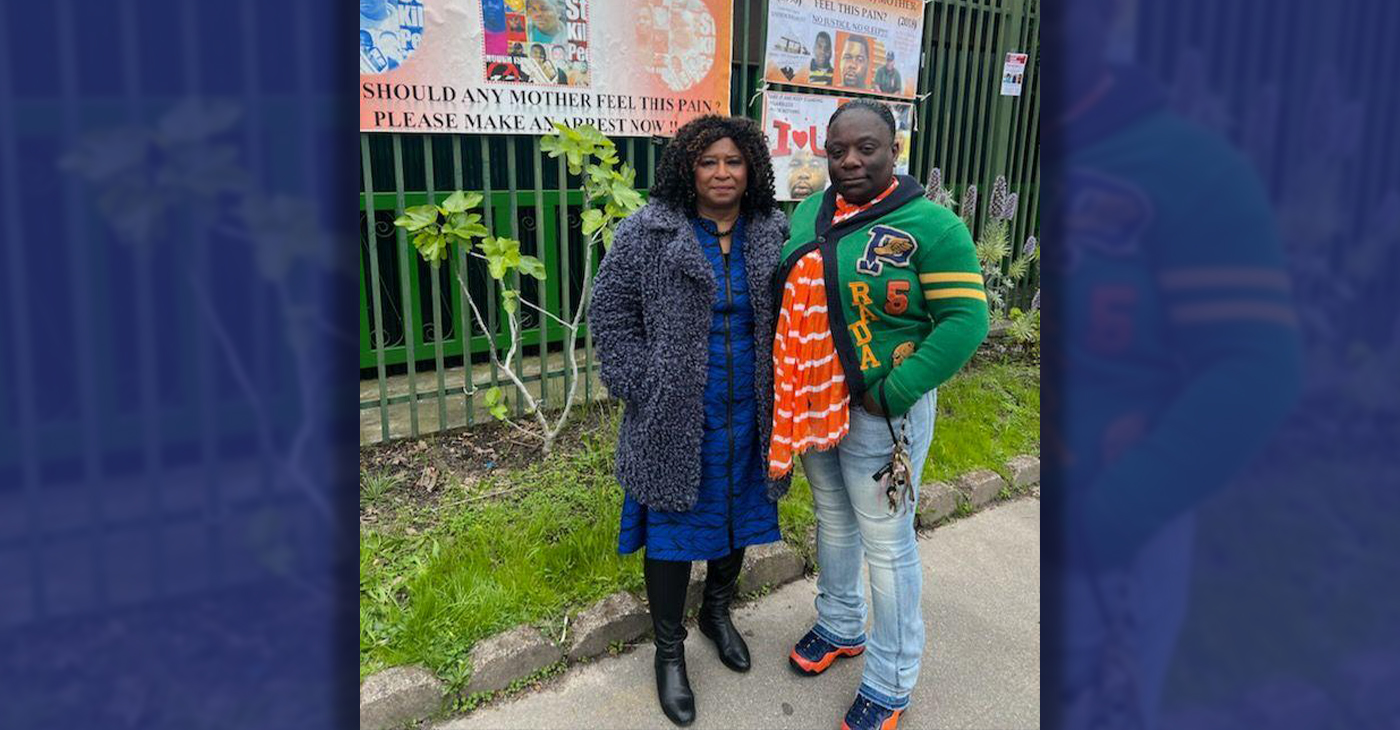

Last week, The Post published a photo showing Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price with Carol Jones, whose son, Patrick DeMarco Scott, was gunned down by an unknown assailant in 2018.

Publisher’s note: Last week, The Post published a photo showing Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price with Carol Jones, whose son, Patrick DeMarco Scott, was gunned down by an unknown assailant in 2018. The photo was too small for readers to see where the women were and what they were doing. Here we show Price and Jones as they complete a walk in memory of Scott. For more information and to contribute, please contact Carol Jones at 510-978-5517 at morefoundation.help@gmail.com. Courtesy photo.

Bay Area

State Controller Malia Cohen Keynote Speaker at S.F. Wealth Conference

California State Controller Malia Cohen delivered the keynote speech to over 50 business women at the Black Wealth Brunch held on March 28 at the War Memorial and Performing Arts Center at 301 Van Ness Ave. in San Francisco. The Enterprising Women Networking SF Chapter of the American Business Women’s Association (ABWA) hosted the Green Room event to launch its platform designed to close the racial wealth gap in Black and Brown communities.

By Carla Thomas

California State Controller Malia Cohen delivered the keynote speech to over 50 business women at the Black Wealth Brunch held on March 28 at the War Memorial and Performing Arts Center at 301 Van Ness Ave. in San Francisco.

The Enterprising Women Networking SF Chapter of the American Business Women’s Association (ABWA) hosted the Green Room event to launch its platform designed to close the racial wealth gap in Black and Brown communities.

“Our goal is to educate Black and Brown families in the masses about financial wellness, wealth building, and how to protect and preserve wealth,” said ABWA San Francisco Chapter President LaRonda Smith.

ABWA’s mission is to bring together businesswomen of diverse occupations and provide opportunities for them to help themselves and others grow personally and professionally through leadership, education, networking support, and national recognition.

“This day is about recognizing influential women, hearing from an accomplished woman as our keynote speaker and allowing women to come together as powerful people,” said ABWA SF Chapter Vice President Velma Landers.

More than 60 attendees dined on the culinary delights of Chef Sharon Lee of The Spot catering, which included a full soul food brunch of skewered shrimp, chicken, blackened salmon, and mac and cheese.

Cohen discussed the many economic disparities women and people of color face. From pay equity to financial literacy, Cohen shared not only statistics, but was excited about a new solution in motion which entailed partnering with Californians for Financial Education.

“I want everyone to reach their full potential,” she said. “Just a few weeks ago in Sacramento, I partnered with an organization, Californians for Financial Education.

“We gathered 990 signatures and submitted it to the [California] Secretary of State to get an initiative on the ballot that guarantees personal finance courses for every public school kid in the state of California.

“Every California student deserves an equal opportunity to learn about filing taxes, interest rates, budgets, and understanding the impact of credit scores. The way we begin to do that is to teach it,” Cohen said.

By equipping students with information, Cohen hopes to close the financial wealth gap, and give everyone an opportunity to reach their full financial potential. “They have to first be equipped with the information and education is the key. Then all we need are opportunities to step into spaces and places of power.”

Cohen went on to share that in her own upbringing, she was not guided on financial principles that could jump start her finances. “Communities of color don’t have the same information and I don’t know about you, but I did not grow up listening to my parents discussing their assets, their investments, and diversifying their portfolio. This is the kind of nomenclature and language we are trying to introduce to our future generations so we can pivot from a life of poverty so we can pivot away and never return to poverty.”

Cohen urged audience members to pass the initiative on the November 2024 ballot.

“When we come together as women, uplift women, and support women, we all win. By networking and learning together, we can continue to build generational wealth,” said Landers. “Passing a powerful initiative will ensure the next generation of California students will be empowered to make more informed financial decisions, decisions that will last them a lifetime.”

Bay Area

MAYOR BREED ANNOUNCES $53 MILLION FEDERAL GRANT FOR SAN FRANCISCO’S HOMELESS PROGRAMS

San Francisco, CA – Mayor London N. Breed today announced that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has awarded the city a $53.7 million grant to support efforts to renew and expand critical services and housing for people experiencing homelessness in San Francisco.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Wednesday, January 31, 2024

Contact: Mayor’s Office of Communications, mayorspressoffice@sfgov.org

***PRESS RELEASE***

MAYOR BREED ANNOUNCES $53 MILLION FEDERAL GRANT FOR SAN FRANCISCO’S HOMELESS PROGRAMS

HUD’s Continuum of Care grant will support the City’s range of critical services and programs, including permanent supportive housing, rapid re-housing, and improved access to housing for survivors of domestic violence

San Francisco, CA – Mayor London N. Breed today announced that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has awarded the city a $53.7 million grant to support efforts to renew and expand critical services and housing for people experiencing homelessness in San Francisco.

HUD’s Continuum of Care (CoC) program is designed to support local programs with the goal of ending homelessness for individuals, families, and Transitional Age Youth.

This funding supports the city’s ongoing efforts that have helped more than 15,000 people exit homelessness since 2018 through City programs including direct housing placements and relocation assistance. During that time San Francisco has also increased housing slots by 50%. San Francisco has the most permanent supportive housing of any county in the Bay Area, and the second most slots per capita than any city in the country.

“In San Francisco, we have worked aggressively to increase housing, shelter, and services for people experiencing homelessness, and we are building on these efforts every day,” said Mayor London Breed. “Every day our encampment outreach workers are going out to bring people indoors and our City workers are connecting people to housing and shelter. This support from the federal government is critical and will allow us to serve people in need and address encampments in our neighborhoods.”

The funding towards supporting the renewal projects in San Francisco include financial support for a mix of permanent supportive housing, rapid re-housing, and transitional housing projects. In addition, the CoC award will support Coordinated Entry projects to centralize the City’s various efforts to address homelessness. This includes $2.1 million in funding for the Coordinated Entry system to improve access to housing for youth and survivors of domestic violence.

“This is a good day for San Francisco,” said Shireen McSpadden, executive director of the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. “HUD’s Continuum of Care funding provides vital resources to a diversity of programs and projects that have helped people to stabilize in our community. This funding is a testament to our work and the work of our nonprofit partners.”

The 2024 Continuum of Care Renewal Awards Include:

- $42.2 million for 29 renewal PSH projects that serve chronically homeless, veterans, and youth

- $318,000 for one new PSH project, which will provide 98 affordable homes for low-income seniors in the Richmond District

- $445,00 for one Transitional Housing (TH) project serving youth

- $6.4 million dedicated to four Rapid Rehousing (RRH) projects that serve families, youth, and survivors of domestic violence

- $750,00 for two Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) projects

- $2.1 million for three Coordinated Entry projects that serve families, youth, chronically homeless, and survivors of domestic violence

In addition, the 2023 CoC Planning Grant, now increased to $1,500,000 from $1,250,000, was also approved. Planning grants are submitted non-competitively and may be used to carry out the duties of operating a CoC, such as system evaluation and planning, monitoring, project and system performance improvement, providing trainings, partner collaborations, and conducting the PIT Count.

“We are very appreciative of HUD’s support in fulfilling our funding request for these critically important projects for San Francisco that help so many people trying to exit homelessness,” said Del Seymour, co-chair of the Local Homeless Coordinating Board. “This funding will make a real difference to people seeking services and support in their journey out of homelessness.”

In comparison to last year’s competition, this represents a $770,000 increase in funding, due to a new PSH project that was funded, an increase in some unit type Fair Market Rents (FMRs) and the larger CoC Planning Grant. In a year where more projects had to compete nationally against other communities, this represents a significant increase.

Nationally, HUD awarded nearly $3.16 billion for over 7,000 local homeless housing and service programs including new projects and renewals across the United States.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

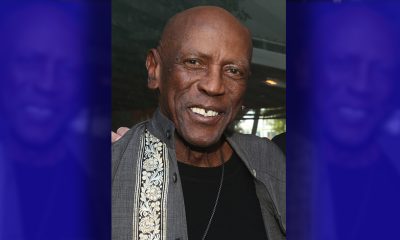

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024