Activism

COMMENTARY: Apology for Japanese American Internment Prompts Equal Response to Injustices Against Black Californians

By Joe W. Bowers Jr. | California Black Media

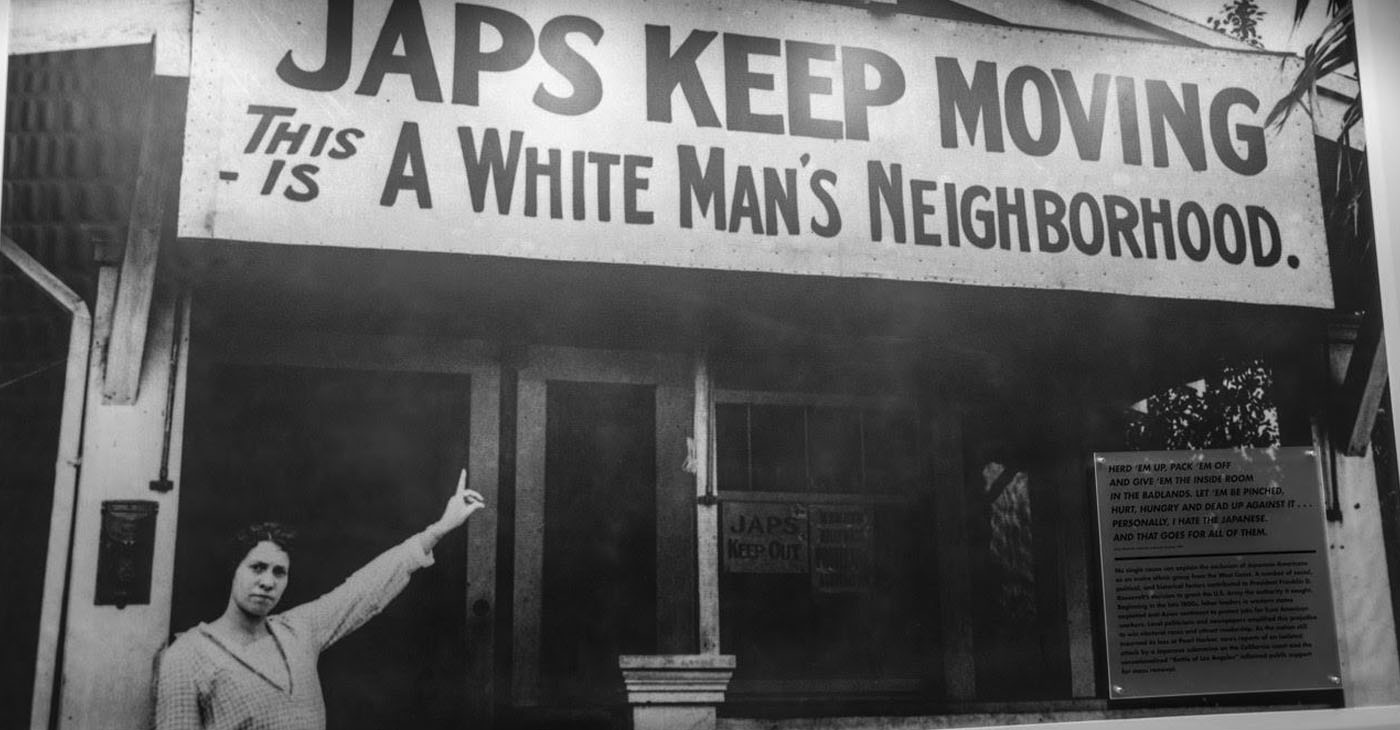

In August, the California Attorney General’s Office publicly apologized for its role in the unjust incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. This belated acknowledgement highlights America’s capacity for prejudice.

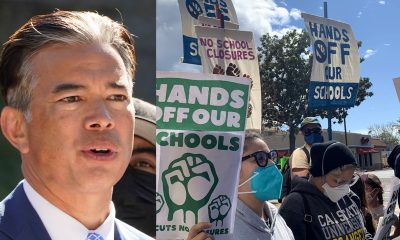

Attorney General Rob Bonta’s apology, issued on the 35th anniversary of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, recognized that his office had used legal tools to deprive a generation of Japanese Californians of their liberty and financial security.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988, signed by President Ronald Reagan, not only authorized compensation for wrongfully interned Japanese Americans but also included a formal presidential apology and established a public education fund to prevent similar injustices.

Retired Assemblymember Mariko Yamada, who represented the 4th District and whose family experienced internment, praised Bonta’s action, stating, “I applaud Rob Bonta for acknowledging the past complicity of the Office of CA Attorney General in the wartime Japanese American incarceration and its associated land grabs. It’s never too late to correct an injustice — words matter, and courageous actions mean even more.”

Bonta acknowledged that more work is needed to address the legacy of Japanese American internment and stressed the importance of treating all Californians equally.

In his apology, he referred to the nationwide surge in anti-Asian hate crimes and the ongoing struggle for racial justice, invoking the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s words, “A time comes when silence is betrayal,” as a call against complacency.

The historical injustices faced by Japanese Americans and Black Californians, while by no means equal, share undeniable parallels. Both communities have endured systemic discrimination, economic marginalization, and the inescapable trauma of racial violence.

However, when asked about extending a similar apology to Black Californians for the enduring harms of slavery and its ongoing societal impacts, Bonta’s office did not directly respond.

Although Bonta’s apology is a noteworthy step forward, a critical question lingers: Why has a similar recognition and apology not been extended to Black Californians?

Yamada pointed out to California Black Media (CBM) that the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) recognized the need for government recognition and reparations for the Black community in their Juneteenth 2023 statement.

JACL stated, “In fact this year, even as we remember 35 years ago the successful fight for redress for the Japanese American community, we recognize another 35 years passing without recognition from our government for the need to provide Black reparations.”

Don Tamaki, a Bay Area-based attorney with a history of working for reparations for Japanese Americans, was the only non-Black member of the nine-member California Reparations Task Force. He recognizes the long history of solidarity across the movements.

Tamaki suggests that the reason Japanese Americans have received an apology, while Black Californians have yet to be acknowledged, is rooted in the country’s deep-seated anti-Black bias and a long history of denying Black Americans’ humanity and experiences.

Tamaki’s personal connection to the internment issue offers valuable insights for advocating for a state apology. His parents were recipients of compensation and a formal apology from the federal government. He recalls the political awakening of Japanese Americans in the 1960s, influenced by the Civil Rights Movement and King’s televised demonstrations against racial injustice. Tamaki underscores that the Japanese American redress movement was aided by Black legislators and activists.

As we welcome steps toward accountability by the Attorney General’s office in the case of Japanese American internment, we also urge the state to apply similar principles of acknowledgment and justice across all communities.

Recently, Tamaki, along with the California Black Power Network, the Equal Justice Society, and five other members of the California Reparations Task Force, announced the formation of the Alliance for Reparations, Reconciliation, and Truth.

The Alliance aims to expand support for reparations for eligible Black Californians by diversifying its allies across different races and sectors. Their strategy involves educating the public and advocating for the Reparations Task Force’s recommendations. Alliance leaders have suggested a joint effort with the California Legislative Black Caucus (CLBC) to advance legislation.

Bradford, the CLBC vice chair, indicated that while the caucus hasn’t yet set legislative priorities for implementing the Task Force’s recommendations, an apology for the legacy of slavery could be a key proposal. He stated, “If you were to ask me, an apology has to be front and center.”

In 2008, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a non-binding resolution, apologizing to Black Americans for slavery and for subsequent legal segregation and discrimination. Despite this, neither Congress nor the White House has taken substantial action to redress these historical injustices.

Recognizing the ongoing and cumulative harms experienced by African Americans is an essential part California’s journey towards justice.

This California Black Media report was supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

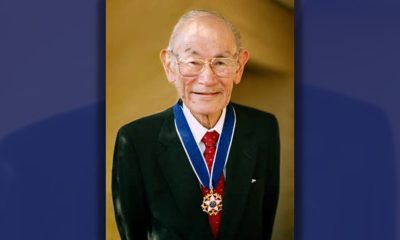

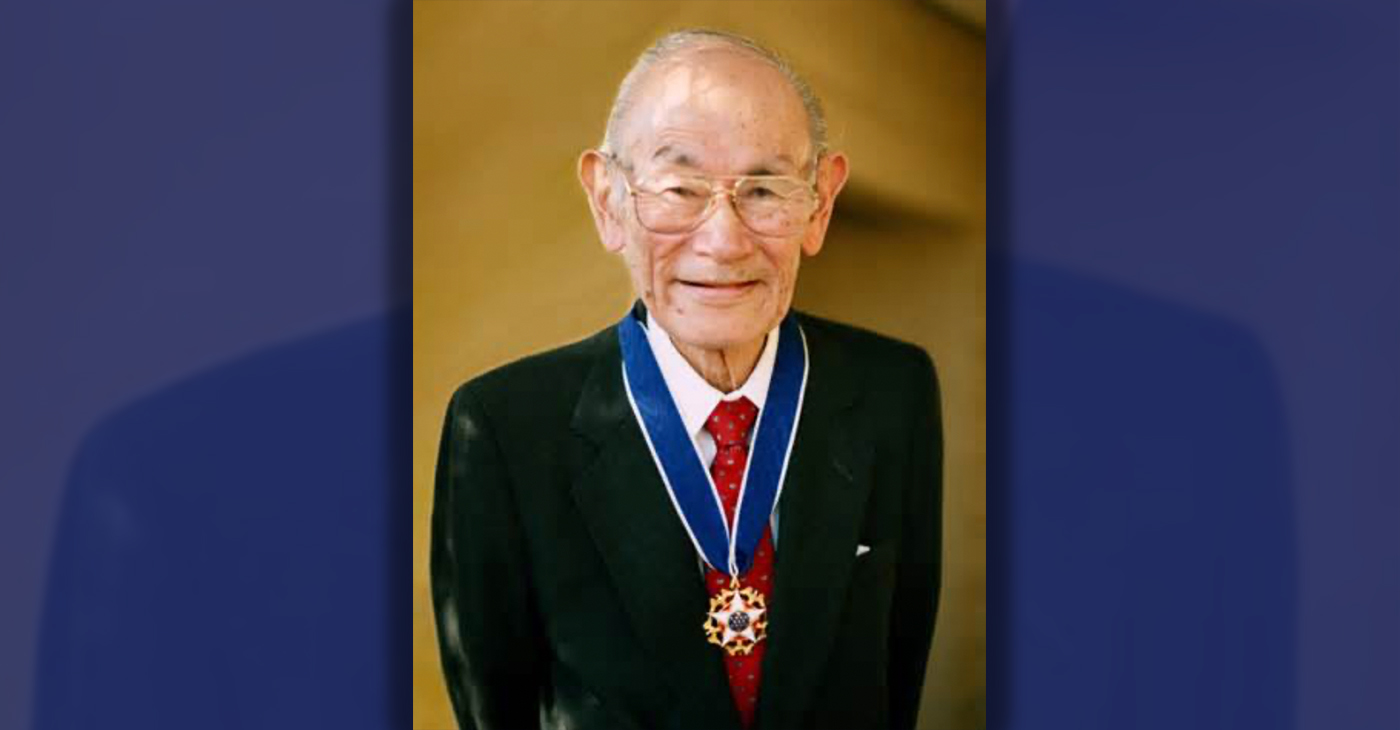

Oakland Schools Honor Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice. His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

By Post Staff

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice.

His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

One OUSD school is named in his honor: Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy (KDA) elementary in East Oakland.

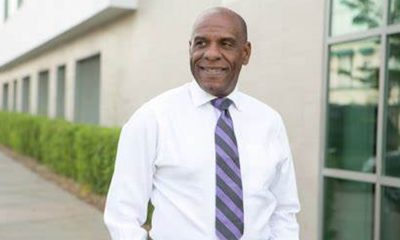

Several years ago, founding KDA Principal Charles Wilson, in a video interview with anti-hate organization “Not In Our Town,” said, “We chose the name Fred Korematsu because we really felt like the attributes that he showed in his work are things that the children need to learn … that common people can stand up and make differences in a large number of people’s lives.”

Fred Korematsu was born in Oakland on Jan. 30, 1919. His parents ran a floral nursery business, and his upbringing in Oakland shaped his worldview. His belief in the importance of standing up for your rights and the rights of others, regardless of race or background, was the foundation for his activism against racial prejudice and for the rights of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the start of the war, Korematsu was turned away from enlisting in the National Guard and the Coast Guard because of his race. He trained as a welder, working at the docks in Oakland, but was fired after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Fear and prejudice led to federal Executive Order 9066, which forced more than 120,000 Japanese Americans out of their homes and neighborhoods and into remote internment camps.

The 23-year-old Korematsu resisted the order. He underwent cosmetic surgery and assumed a false identity, choosing freedom over unjust imprisonment. His later arrest and conviction sparked a legal battle that would challenge the foundation of civil liberties in America.

Korematsu’s fight culminated in the Supreme Court’s initial ruling against him in 1944. He spent years in a Utah internment camp with his family, followed by time living in Salt Lake City where he was dogged by racism.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford overturned Executive Order 9066. Seven years later, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco vacated Korematsu’s conviction. He said in court, “I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong and do something about it so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color.”

Korematsu’s dedication and determination established him as a national icon of civil rights and social justice. He advocated for justice with Rosa Parks. In 1998, President Bill Clinton gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom saying, “In the long history of our country’s constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls … To that distinguished list, today we add the name of Fred Korematsu.”

After Sept. 11, 2001, Korematsu spoke out against hatred and discrimination, saying what happened to Japanese Americans should not happen to people of Middle Eastern descent.

Korematsu’s roots in Oakland and his education in OUSD are a source of great pride for the city, according to the school district. His most famous quote, which is on the Korematsu elementary school mural, is as relevant now as ever, “If you have the feeling that something is wrong, don’t be afraid to speak up.”

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoAG Bonta Says Oakland School Leaders Should Comply with State Laws to Avoid ‘Disparate Harm’ When Closing or Merging Schools

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoOakland WNBA Player to be Inducted Into Hall of Fame