Activism

Remembering Berkeley Homeless Advocate and Former Mayor Candidate Mike Lee

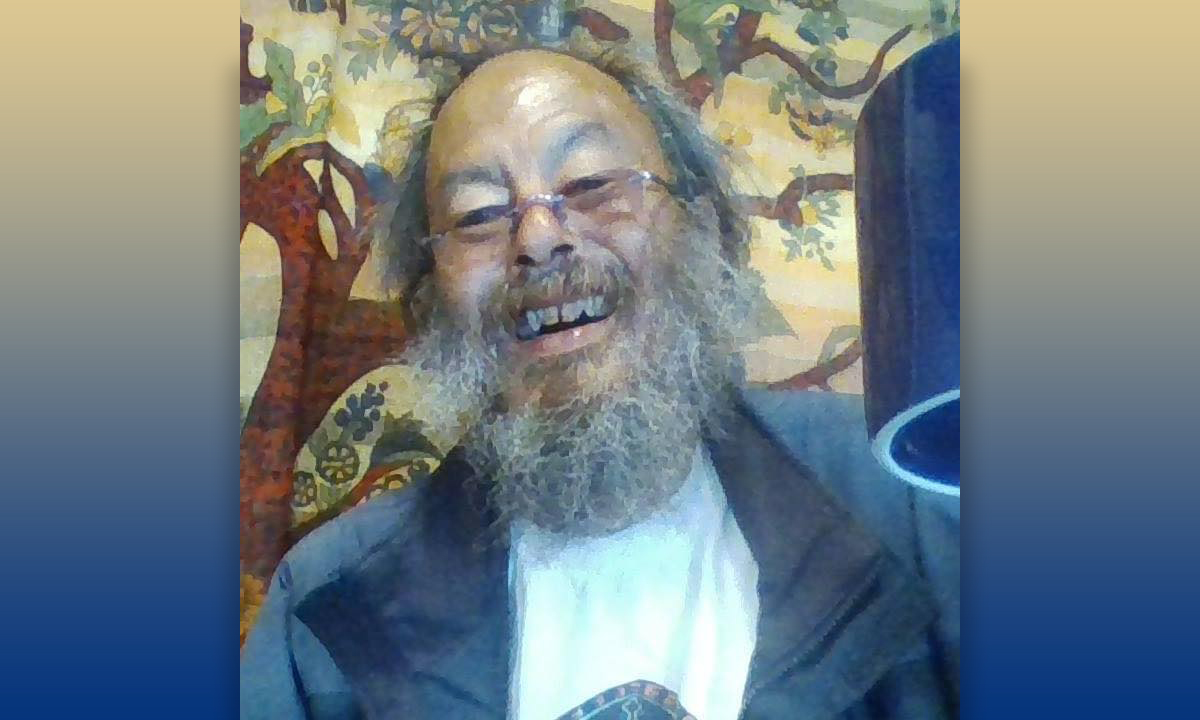

Activist and former Berkeley mayoral candidate Mike Lee died at age 64 of complications related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease early in the week of Aug. 2, 2020.

Housing activists and many people experiencing homelessness across Berkeley, Oakland and San Francisco expressed sadness at his loss and admiration for him in the wake of the news.

“He was an incredibly compassionate yet strong individual,” said Paul-Kealoha Blake, who has done homeless advocacy work in Berkeley for over two decades.

Starting in the mid-2010s, while Lee himself was unhoused, Blake would meet with him and other unhoused people regularly at the McDonald’s on Shattuck and University avenues to strategize about how to advocate best for unhoused people’s rights in general and to help them access services.

Many of the people Lee met were unhoused youth. He would help them secure shelter through local nonprofits and city programs.

“All of the kids knew him,” said Blake. “He knew the ropes and provided them with realistic inspiration. It’s one thing to talk to a kid and tell how they’re gonna have housing but it’s another to talk to a kid and say ‘It may be months before you get housing. It doesn’t matter. We’ve gotta do it anyway.’”

According to Blake, Lee went to that McDonalds because he knew it as a place where unhoused people hung out.

“We can’t expect vulnerable people to track us down,” said Blake. “That was definitely where Mike Lee was at. You go where people are at to talk to them: intellectually, emotionally, psychologically, as well and physically. He was incredible in that way.”

Oakland native and unhoused resident Preston Walker, better known as Pastor Preston, reports that Lee regularly came to homeless evictions in Oakland, sometimes deep into the eastern part of the town that sits farther away from Berkeley. He would help people stay as safe as possible and keep their possessions, which were under threat of destruction or disposal by the Oakland police and Dept. of Public Works. Health problems forced him to use a cane or a wheelchair but he still navigated public transportation to be present at evictions.

“It’s easier to talk to someone that’s unhoused when you’re unhoused,” said Walker, who remembers Lee as relating well to those being evicted, many who were, like Lee, also older and/or disabled.

Lee knew what it was like to be evicted as an unhoused person from his experiences in Berkeley and he stood up for his rights.

“He always had that warm smile but he never backed down to nobody,” said Walker.

In March 2017, Lee sued the City of Berkeley, claiming the city violated his constitutional rights in October 2016 during an eviction by destroying his property. Also in 2016, Lee made his most public fight for unhoused rights when he ran for Berkeley mayor.

“The idea was never that he was going to be mayor,” said Blake.

Lee used his platform to bring issues of housing and homelessness into Berkeley’s political and public discourse. According to Blake, who worked on the campaign, he and Lee had frank discussions about how it was impossible for him to win as he was not “running against a person but a machine.”

Rejecting respectability politics and the desire to appeal to everyone, Lee’s campaign, much the way his friends described his personality, had a cantankerous humor to it. Lee and his supporters put signs and stickers throughout town that read “Old bum for Mayor.”

He also used his platform to be serious. During a speech on Nov 7, 2016, Election Day, Lee described a brutal attack he alleges Berkeley Police executed against unhoused residents just three days before. During the same speech, he said,“Homelessness describes an economic condition, not a person.”

Lee’s mayoral run brought him into the mainstream Berkeley public’s eye but many activists in Berkeley and Oakland first met Lee in 2014, during the Berkeley Post Office occupation.

He, along with Walker, Mike Zint and several other unhoused people, lived in front of the post office at 2000 Allston Way for months in 2014, at times gathering large crowds to protest the sale of the building to a developer, Hudson McDonald, with whom USPS was negotiating a sale.

In September of that year, after massive public pressure, the city declared a Historic Civic Center District Overlay, which protected the post office that had been built in the 1800s from being sold.

Lee had deep roots in the Bay Area. He grew up in Portland, Ore., but moved with an uncle to Daly City at age 13, then moved to San Francisco at age 17. San Francisco activist and poet, Sarah Menefee, remembers Lee when he was “handsome and skinny,” and first met him in 1987. Her memories show that he was involved in activism and fighting for the rights of unhoused people at least since he was in his early 30s.

“He was always there with a take-no-prisoners attitude about homeless people having to stand up, be militant, speak for themselves, and not just be fodder for these non-profits,” said Menefee.

In the late ’80s, while he was living in SRO housing in San Francisco, Lee and Menefee helped organize an S.F. chapter of the National Union of the Homeless. Through the union, they organized shelter strikes with unhoused residents who they recruited from food lines. Then they would stage protests outside of homeless shelters they felt were mistreating unhoused people.

Menefee attributes this public pressure to the Coalition on Homelessness eventually creating rights of appeal which made it harder for nonprofits to kick unhoused people out of shelters for infractions or alleged infractions that they had previously been powerless to challenge.

In the ’90s, Menefee lost track of Lee and said she heard he moved to Las Vegas. Over two decades later she reunited with him at the post office occupation.

In September 2018, Lee secured housing through the Homeless Coordinated Entry System, a program he had long criticized. Menefee suspected that the City of Berkeley sheltered him thinking “it would shut him up.”

But soon after being housed, he publicly claimed in an article in The Daily Californian that he suspected his prominent status is what got him housed and that he worried others would not get the same opportunity.

“We may have won this battle, but we haven’t won the war yet,” Lee is quoted saying in the article. “So, it’s a start. One down, thousands more to go.”

Lee kept showing up to evictions and organizing with unhoused people. He also shared his apartment with other unhoused people, allowing them prolonged stays.

Up until his final years Lee sought out unhoused people to organize with. After seeing Oakland resident Derrick Soo broadcasting on Facebook about his situation experiencing homelessness in deep East Oakland in 2018, Lee tracked Soo down.

Impressed with what he saw in the small community where Soo said people got along well and took care of the space despite a lack of city services, Lee helped the people there get better tents and make connections with local food banks.

He named the community the 77th Ave Rangers and got people in the surrounding area and the media to visit the site to, according to Soo, “see who the homeless people are and not just their imagined stereotype.”

Eventually, Lee and Soo were able to successfully get portable toilets, weekly trash pick-up, and an agreement with the city for the police and the Public Works Dept. to leave the site alone.

“For a while the city had even hired a housing coordinator for us,” said Soo, “but that didn’t work out because there’s no housing to coordinate the homeless into.”

Lee acted as a mentor for Soo. For about a year, up until about a month before Lee’s death, they would message each other every morning.

“After our first meeting sitting down, eating lunch together, he said ‘you know, you should run for mayor,’ ” said Soo.

After a discussion involving more encouragement from Lee, Soo was convinced. He plans to run for mayor of Oakland in 2022.

Caption: Derrick Soo, a friend of Mike Lee, standing in front of equipment he uses to broadcast about his experiences with homelessness on Facebook on Aug 10. Photo by Zack Haber

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Schools Honor Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice. His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

By Post Staff

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice.

His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

One OUSD school is named in his honor: Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy (KDA) elementary in East Oakland.

Several years ago, founding KDA Principal Charles Wilson, in a video interview with anti-hate organization “Not In Our Town,” said, “We chose the name Fred Korematsu because we really felt like the attributes that he showed in his work are things that the children need to learn … that common people can stand up and make differences in a large number of people’s lives.”

Fred Korematsu was born in Oakland on Jan. 30, 1919. His parents ran a floral nursery business, and his upbringing in Oakland shaped his worldview. His belief in the importance of standing up for your rights and the rights of others, regardless of race or background, was the foundation for his activism against racial prejudice and for the rights of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the start of the war, Korematsu was turned away from enlisting in the National Guard and the Coast Guard because of his race. He trained as a welder, working at the docks in Oakland, but was fired after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Fear and prejudice led to federal Executive Order 9066, which forced more than 120,000 Japanese Americans out of their homes and neighborhoods and into remote internment camps.

The 23-year-old Korematsu resisted the order. He underwent cosmetic surgery and assumed a false identity, choosing freedom over unjust imprisonment. His later arrest and conviction sparked a legal battle that would challenge the foundation of civil liberties in America.

Korematsu’s fight culminated in the Supreme Court’s initial ruling against him in 1944. He spent years in a Utah internment camp with his family, followed by time living in Salt Lake City where he was dogged by racism.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford overturned Executive Order 9066. Seven years later, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco vacated Korematsu’s conviction. He said in court, “I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong and do something about it so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color.”

Korematsu’s dedication and determination established him as a national icon of civil rights and social justice. He advocated for justice with Rosa Parks. In 1998, President Bill Clinton gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom saying, “In the long history of our country’s constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls … To that distinguished list, today we add the name of Fred Korematsu.”

After Sept. 11, 2001, Korematsu spoke out against hatred and discrimination, saying what happened to Japanese Americans should not happen to people of Middle Eastern descent.

Korematsu’s roots in Oakland and his education in OUSD are a source of great pride for the city, according to the school district. His most famous quote, which is on the Korematsu elementary school mural, is as relevant now as ever, “If you have the feeling that something is wrong, don’t be afraid to speak up.”

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoAG Bonta Says Oakland School Leaders Should Comply with State Laws to Avoid ‘Disparate Harm’ When Closing or Merging Schools

-

Community6 days ago

Community6 days agoOakland WNBA Player to be Inducted Into Hall of Fame