Activism

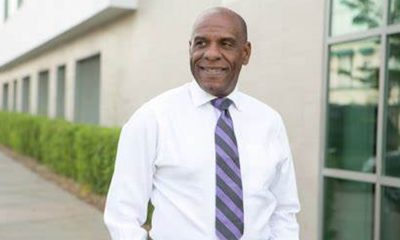

State Education Chief Thurmond Weighs Successes, Setbacks

Regarding commentary about his public visibility during the COVID-19 crisis, Tony Thurmond, State Superintendent of Public Instruction (SSPI)’s view is, “The way this job works, there’s a piece of it that people will never see. But I’d like to think that we have been the glue between school leaders, legislators, and the governor. In my role, we’ve had to be that glue between those entities, and that interplays on how decision-making happens.”

By Joe W. Bowers Jr. | California Black Media

When Tony Thurmond, State Superintendent of Public Instruction (SSPI) was elected in 2018, he became the second African American in the office since the 1849 California Constitution established it. Wilson Riles was California’s and the nation’s first Black SSPI. In 1970, he also was the first African American voted to hold any statewide office in California.

Recently, Thurmond spoke to California Black Media (CBM) about his experience as the state’s highest elected Education official. He says the COVID-19 pandemic has been the defining challenge of his tenure.

It affected everything — from requiring him to suddenly draft a revised strategy for supporting schools to keeping students and staff safe. He did this while taking steps to improve the overall quality of public education.

“March 13, 2020. March 13, I’ll never forget it,” Thurmond told CBM. He was in his office when he started to receive calls “asking ‘what are we going to do?’ as school districts announced that they were closing to mitigate the spread of the virus.

Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic forced Thurmond to delay action on the initiatives he identified as priorities when he entered office.

Opening schools safely and dealing with the specific systemic inequities, particularly experienced by students of color, had to be tackled first.

The California Department of Education’s (CDE) action plan included securing 2 million masks for schools and working with the governor’s office to obtain five million rapid COVID tests.

While schools were closed, the state’s education department supplied over 500 million meals to students and families. When vaccinations became available, CDE developed a campaign that encouraged staff and students to get vaccinated.

While it was up to each school district to decide how it would deal with the COVID-19 crisis, Thurmond hosted weekly meetings with all county superintendents to talk through plans for reopening schools safely.

As distance learning became necessary, inequities in access to technology were exposed. One-fifth of California students lacked the resources to continue their education from home, either due to no internet connectivity or not owning a computer at home — or both.

To find a solution to the problem, Thurmond assembled a committee he named “Closing the Digital Divide Task Force.”

“We put legislators on that committee by design. We knew that in order to get the attention of the internet providers, they need to see legislators,” Thurmond said.

As a result, the state was able to provide computers and hotspots, enhancing internet connectivity to over 400 school districts across nearly all of California’s 58 counties. According to Thurmond, “There is about $6 billion for building out broadband in this year’s state budget. The task force helped to lay the foundation for that.”

Thurmond points out that state law grants the SSPI limited authority over California’s public education policies, funding and infrastructure. But despite his restricted power, Thurmond views the SSPI role as much more than being a figurehead. As one of only eight statewide elected officials, voters have given him a prominent bully pulpit from which he can influence education policy.

“They said the office doesn’t have a lot of tools to get things done directly, but I felt very confident using my relationships with the Legislature and the governor that I could find a way to put a spotlight on big problems and find ways to influence them even though it would have to happen in an indirect way,” Thurmond said.

The governor and the Legislature determine state funding for education and set policy direction. The State Board of Education determines academic standards, curriculum, instructional materials, assessments, and accountability.

The SSPI has no legal authority over the 1,000 local school districts in the state. Each of the state’s 58 county offices of education — not the SSPI — approve school districts’ budgets and provide assistance and instruction on how they can improve their educational programs.

Thurmond’s main job is to run the day-to-day operations of the CDE, which has about 2,600 employees and enforces California’s education laws and regulations. It also administers federal and state education programs and oversees federal education grant compliance.

In addition, it performs certain administrative tasks, such as collecting and compiling statewide data on district spending and student performance.

In 2018, Thurmond decided to not to seek another Assembly term and run to be SSPI instead. That way, he could work full time on education issues. At the time, he was a two-term Assemblymember representing the 51st Assembly District in the Bay Area.

A popular politician among his constituents, Thurmond received 90% of the vote during his last Assembly election.

For Thurmond, education is the great equalizer. He says it allows children to overcome challenging circumstances and it provides paths to opportunities for all of California’s kids. He started his term as SSPI by proposing an ambitious eight-year plan to significantly boost school funding and expand early childhood education.

Beginning with his first month in office, Thurmond formed 13 transition teams with over 1,000 people. Those teams focused on his top priority: closing racial and economic achievement and opportunity gaps in a state where African American and Latino kids score below statewide standards on achievement tests.

Town halls and webinars focused on Black and Brown student achievement became the genesis for his initiative supporting funding to diversify the teacher workforce.

Now that school districts have adopted the safety protocols like masking, vaccinations, and testing necessary to stay open for in-person learning, Thurmond says he has again turned his attention to pursuing pre-pandemic initiatives.

In September, he launched a literacy goal to make sure all third-graders are able to read by 2026. He also appointed the Task Force to Improve Black Student Achievement.

Thurmond told CBM, “I feel like I’m in a place now where, like Maxine Waters says, ‘I’m reclaiming my time.’ I came to the department thinking I’d have eight years to work on third-grade literacy, and that got undercut because of the pandemic.”

Funding from the state and federal government for California’s public education is at a historic high. As a result, money is available for initiatives advocated by Thurmond like universal Pre-K and universal meals, community schools, family engagement and mental health services for students.

At his inauguration, Thurmond told the audience, “This job is the type of job where you get all the blame for what goes wrong, but you don’t have the resources to fix what needs to be fixed.”

Although at the time Thurmond was speaking generally, his observation could apply to recent criticisms leveled at him in the media about the high turnover of his senior staff.

Thurmond thinks that CDE is underfunded and insufficiently staffed to be able to handle its bureaucratic responsibilities and support the initiatives that he sees as public education priorities. He says, “I’ve taken some time to think about how to structure the organization and how to restructure it.”

Regarding commentary about his public visibility during the COVID-19 crisis, Thurmond’s view is, “The way this job works, there’s a piece of it that people will never see. But I’d like to think that we have been the glue between school leaders, legislators, and the governor. In my role, we’ve had to be that glue between those entities, and that interplays on how decision-making happens.”

Thurmond does not have a button he can push to make something happen in California public schools. But he does have a microphone to broadcast where problems are and the good news is because he has the relationships he is in a position to influence education policy for the benefit of California’s public education students.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

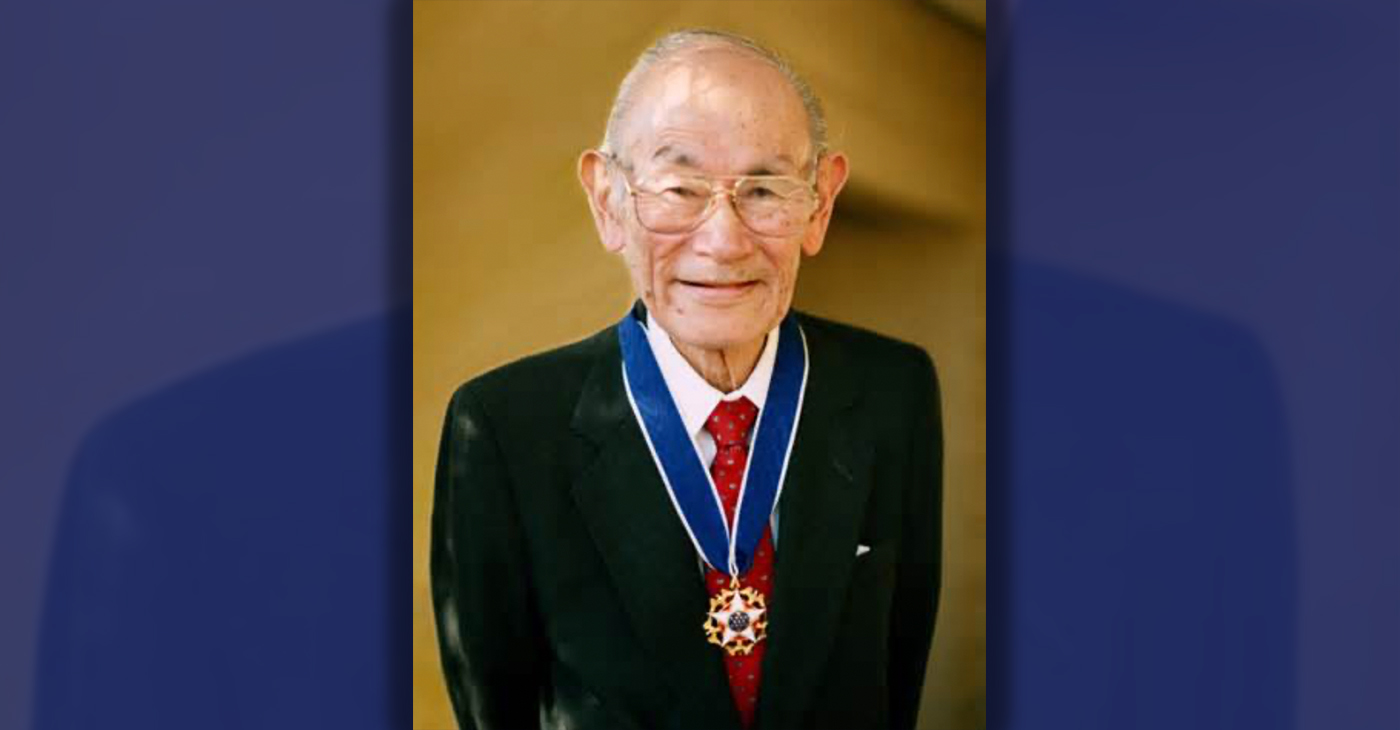

Oakland Schools Honor Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice. His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

By Post Staff

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice.

His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

One OUSD school is named in his honor: Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy (KDA) elementary in East Oakland.

Several years ago, founding KDA Principal Charles Wilson, in a video interview with anti-hate organization “Not In Our Town,” said, “We chose the name Fred Korematsu because we really felt like the attributes that he showed in his work are things that the children need to learn … that common people can stand up and make differences in a large number of people’s lives.”

Fred Korematsu was born in Oakland on Jan. 30, 1919. His parents ran a floral nursery business, and his upbringing in Oakland shaped his worldview. His belief in the importance of standing up for your rights and the rights of others, regardless of race or background, was the foundation for his activism against racial prejudice and for the rights of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the start of the war, Korematsu was turned away from enlisting in the National Guard and the Coast Guard because of his race. He trained as a welder, working at the docks in Oakland, but was fired after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Fear and prejudice led to federal Executive Order 9066, which forced more than 120,000 Japanese Americans out of their homes and neighborhoods and into remote internment camps.

The 23-year-old Korematsu resisted the order. He underwent cosmetic surgery and assumed a false identity, choosing freedom over unjust imprisonment. His later arrest and conviction sparked a legal battle that would challenge the foundation of civil liberties in America.

Korematsu’s fight culminated in the Supreme Court’s initial ruling against him in 1944. He spent years in a Utah internment camp with his family, followed by time living in Salt Lake City where he was dogged by racism.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford overturned Executive Order 9066. Seven years later, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco vacated Korematsu’s conviction. He said in court, “I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong and do something about it so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color.”

Korematsu’s dedication and determination established him as a national icon of civil rights and social justice. He advocated for justice with Rosa Parks. In 1998, President Bill Clinton gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom saying, “In the long history of our country’s constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls … To that distinguished list, today we add the name of Fred Korematsu.”

After Sept. 11, 2001, Korematsu spoke out against hatred and discrimination, saying what happened to Japanese Americans should not happen to people of Middle Eastern descent.

Korematsu’s roots in Oakland and his education in OUSD are a source of great pride for the city, according to the school district. His most famous quote, which is on the Korematsu elementary school mural, is as relevant now as ever, “If you have the feeling that something is wrong, don’t be afraid to speak up.”

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024

-

Community1 week ago

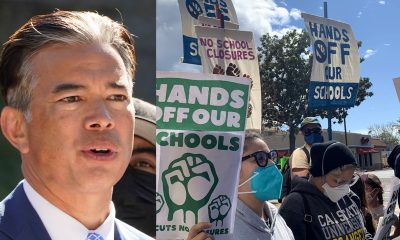

Community1 week agoAG Bonta Says Oakland School Leaders Should Comply with State Laws to Avoid ‘Disparate Harm’ When Closing or Merging Schools

-

Community6 days ago

Community6 days agoOakland WNBA Player to be Inducted Into Hall of Fame