Community

Scenes from a Memphis job fair: How one veteran teacher is struggling to return to the kindergarten classroom

NEW TRI-STATE DEFENDER — here’s still three weeks before school starts in Memphis, but on a recent afternoon, the parking lot at Hickory Ridge Middle School was packed. Veteran kindergarten teacher Sandra Jenkins pulled up at 3:17 p.m. and parked her sage green Toyota Corolla along a curb on the campus outskirts. At Shelby County Schools district’s biggest job fair of the year, other prospective teachers had already taken every spot before the massive hiring event officially started at 3 p.m.

By Kathryn Palmer

There’s still three weeks before school starts in Memphis, but on a recent afternoon, the parking lot at Hickory Ridge Middle School was packed.

Veteran kindergarten teacher Sandra Jenkins pulled up at 3:17 p.m. and parked her sage green Toyota Corolla along a curb on the campus outskirts. At Shelby County Schools district’s biggest job fair of the year, other prospective teachers had already taken every spot before the massive hiring event officially started at 3 p.m.

Ninety-seven percent of district positions are already spoken for. But like every year, a few positions in every grade and almost every subject remain open. This is the fifth teacher job fair in the region Jenkins has attended in the past 12 months. So far, she’s only been able to land substitute positions, but she’s hoping to go home from this hiring event with something more permanent.

For schools with vacancies, this time of year is “crunch time,” said Desmond Hendricks as he set up an interview table in the school gymnasium. He is a social studies teacher at Raleigh Egypt Middle School and was waiting to field candidates for five open positions in math and English. “It’s all about finding the right fit,” he said.

That’s why he joined about 75 other district schools in the gymnasium and cafeteria, prepared to interview candidates and make tentative hiring offers for dozens of vacant positions in Tennessee’s largest district.

Jenkins, 60, is hopeful she’ll be a good fit for one of those schools. The Memphis native is just one of the 224 people who showed up at the two-hour event, hoping to nail down a full-time job before school starts in mid-August. But her silver-streaked ponytail set her apart from the mass of relatively young-looking, recently certified teachers — many of whom were probably born after Jenkins started her first long term substitute teaching job at Whitehaven Elementary in 1981.

“We didn’t have job fairs back then,”Jenkins recalled, as she carefully walked through the parking lot in her marshmallow-white tennis shoes and compression socks. “We just applied to the district and got hired. Now it’s all politics and paperwork.”

As she opened the heavy double doors to start her job hunt, Jenkins passed a young, well-dressed woman skipping back into the parking lot, gleefully proclaiming, “I got the job!” into her cell phone.

“It feels like they only want young ones now,” said Jenkins, who has more than 30 years of classroom experience in Memphis public schools.

Jenkins’ age and experience level make her an outlier in the Memphis teacher workforce, which is plagued by high turnover that creates a pool of inexperienced educators. In the 2015-16 school year, approximately one in five Tennessee teachers were in their first or second years of work, according to data that schools reported to the federal government. Those figures were even higher in Memphis.

Jenkins came armed with a manilla folder containing a stack of resumes and a pitch about herself. Helping young students reach their highest potential is her broad goal, but her specific goal is to get back to teaching kindergarten. She did that for 22 years until a car accident forced her into an unexpected, early retirement from her position at Holmes Road Elementary five years ago. She took some time off to be with family and care for a now-deceased neighbor.

“I’m trying to get back into teaching, but it’s been hard,” she said.

For Jenkins, who has no children of her own, kindergarten is the only grade she can see herself teaching. “They are like my kids,” she said, as she waited in line to check in with district staff and verify her certification. “Some children that I have taught were complete blank slates when they walked into my class. I like molding them, shaping them, building their confidence.”

A district employee hands Jenkins a printout of the job openings, directing Jenkins to the school cafeteria for K-8 openings.

She scans the list looking for kindergarten openings while she walks down a corridor toward the lunchroom. Instead of sandwiches and juice boxes, job ads and interview questionnaires are strewn across the circular tables. School personnel are seated on the built-in benches, ready to interview teachers, ready to make offers.

Jenkins snakes through the maze of teachers and administrators. “I knew I’d see a bunch of people I know,” she said, smiling after spotting an old colleague, Sarah Hamer, who now works as a personal learning coach for White Station Elementary. Hamer’s looking to hire for first grade — not quite what Jenkins is looking for. “I get it. When you’re a kindergarten teacher, you’re a kindergarten teacher for life,” Hamer said to Jenkins. “If you change your mind, we’d love to interview you.”

Jenkins drops off a few resumes at other tables, careful not to interrupt interviews. Then, finally, she gets invited to sit down at the Sheffield Elementary School table for five minutes. The school has an opening for kindergarten, but they’ve already interviewed a few other candidates. They said they’d keep her resume on file.

“If people don’t like me, I move on,” Jenkins said. “Rejection doesn’t hurt me. I was one of the first black students to integrate Whitehaven Elementary in 1967. I got spit on, called names. I don’t take it personally.”

The big round clock on the white cinder block walls ticks to 4:55. By that point Jenkins had handed out almost every copy of her resume, and the crowd is thinning.

On her way out, she bumped into another former coworker, now-assistant superintendent Rodney Rowan. Jenkins told him the day hadn’t gone as well as she’d hope.

Rowan seemed surprised. “I would hire a seasoned teacher in a heartbeat,” he said, “because they don’t require as much training.” He said Jenkins could list him as a reference and he’d tell the schools: “You love children. You work hard. You stayed until the job was done. You didn’t watch the clock.”

As of 5 p.m., when the job fair ended, district recruitment and staffing associate Sheilaine Moses said they’d received 40 hiring recommendations, pending district approval. Jenkins’ name wasn’t among them.

“There’s still a few weeks before school,” Jenkins said as she walked out to the far end of now-emptied school parking lot. “It will happen if it’s supposed to.”

The post Scenes from a Memphis job fair: How one veteran teacher is struggling to return to the kindergarten classroom appeared first on Chalkbeat.

This article originally appeared in the New Tri-State Defender

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 24 – 30, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Alameda County

DA Pamela Price Stands by Mom Who Lost Son to Gun Violence in Oakland

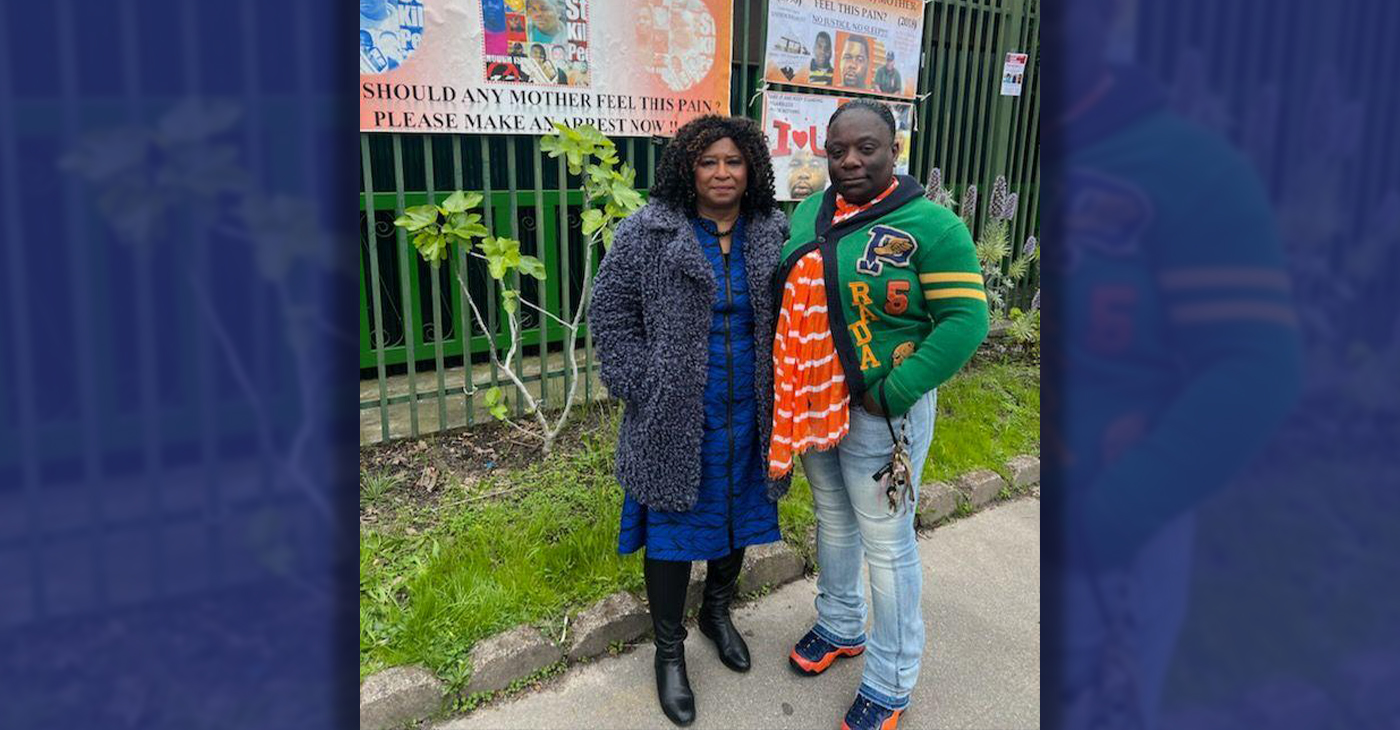

Last week, The Post published a photo showing Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price with Carol Jones, whose son, Patrick DeMarco Scott, was gunned down by an unknown assailant in 2018.

Publisher’s note: Last week, The Post published a photo showing Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price with Carol Jones, whose son, Patrick DeMarco Scott, was gunned down by an unknown assailant in 2018. The photo was too small for readers to see where the women were and what they were doing. Here we show Price and Jones as they complete a walk in memory of Scott. For more information and to contribute, please contact Carol Jones at 510-978-5517 at morefoundation.help@gmail.com. Courtesy photo.

City Government

Vallejo Welcomes Interim City Manager Beverli Marshall

At Tuesday night’s Council meeting, the Vallejo City Council appointed Beverli Marshall as the interim city manager. Her tenure in the City Manager’s Office began today, Wednesday, April 10. Mayor Robert McConnell praised Marshall’s extensive background, noting her “wide breadth of experience in many areas that will assist the City and its citizens in understanding the complexity of the many issues that must be solved” in Vallejo.

Special to The Post

At Tuesday night’s Council meeting, the Vallejo City Council appointed Beverli Marshall as the interim city manager. Her tenure in the City Manager’s Office began today, Wednesday, April 10.

Mayor Robert McConnell praised Marshall’s extensive background, noting her “wide breadth of experience in many areas that will assist the City and its citizens in understanding the complexity of the many issues that must be solved” in Vallejo.

Current City Manager Michael Malone, whose official departure is slated for April 18, expressed his well wishes. “I wish the City of Vallejo and Interim City Manager Marshall all the best in moving forward on the progress we’ve made to improve service to residents.” Malone expressed his hope that the staff and Council will work closely with ICM Marshall to “ensure success and prosperity for the City.”

According to the Vallejo Sun, Malone stepped into the role of interim city manager in 2021 and became permanent in 2022. Previously, Malone served as the city’s water director and decided to retire from city service e at the end of his contract which is April 18.

“I hope the excellent work of City staff will continue for years to come in Vallejo,” he said. “However, recent developments have led me to this decision to announce my retirement.”

When Malone was appointed, Vallejo was awash in scandals involving the housing division and the police department. A third of the city’s jobs went unfilled during most of his tenure, making for a rocky road for getting things done, the Vallejo Sun reported.

At last night’s council meeting, McConnell explained the selection process, highlighting the council’s confidence in achieving positive outcomes through a collaborative effort, and said this afternoon, “The Council is confident that by working closely together, positive results will be obtained.”

While the search for a permanent city manager is ongoing, an announcement is expected in the coming months.

On behalf of the City Council, Mayor McConnell extended gratitude to the staff, citizen groups, and recruitment firm.

“The Council wishes to thank the staff, the citizens’ group, and the recruitment firm for their diligent work and careful consideration for the selection of what is possibly the most important decision a Council can make on behalf of the betterment of our City,” McConnell said.

The Vallejo Sun contributed to this report.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024

-

Community2 weeks ago

Community2 weeks agoAG Bonta Says Oakland School Leaders Should Comply with State Laws to Avoid ‘Disparate Harm’ When Closing or Merging Schools

-

Community7 days ago

Community7 days agoOakland WNBA Player to be Inducted Into Hall of Fame