Activism

Healing Domestic Violence: “It Has to Be Heart Stuff’

As Wilhelmenia “Mina” Wilson grew older, she went through her own traumatic experiences. As a young woman, she, too, became a victim to domestic violence. “The only way I was able to save myself was to remove myself. And not only did I leave the environment, but he knew where I worked. I left my job. I left and created a new life for myself,” she said. “And in removing myself, what I had to do also was stay by myself until I could heal myself. And that took some years.”

By Charlene Muhammad, Special to the Oakland Post

Wilhelmenia “Mina” Wilson, executive director of Healthy Black Families, Inc., in Berkeley grew up in a nuclear family in the Bay Area.

Her parents met in college and were each other’s first love. Still, there was trauma.

As Wilson grew older, she went through her own traumatic experiences. As a young woman, she, too, became a victim to domestic violence.

“The only way I was able to save myself was to remove myself. And not only did I leave the environment, but he knew where I worked. I left my job. I left and created a new life for myself,” she said. “And in removing myself, what I had to do also was stay by myself until I could heal myself. And that took some years.”

To overcome her trauma, Wilson employed some of the techniques she now shares with others as the executive director of Healthy Black Families, Inc.

“I had to learn myself. I had to unpack my trauma. I had to learn to love myself again. And then that allowed me to navigate relationships in a different way,” she said. “So, I’m not really talking from what I think. I’m really talking from what I know, from my own personal experience, and I’d love to try this and see if it works successfully at a macro level as it did for me on a micro one.”

In an interview with Post News Group, Wilson provided her views on the root causes of domestic violence and proposed several viable solutions.

“When you subject people to a lack of human dignity, when people don’t have their basic needs met, that begets a lot of different types of negative behaviors,” she said.

She attributed the causes of domestic violence to how the capitalist system sometimes devalues Black people, and Black women in particular — both of which, from her view, are rooted in slavery. Black women were a commodity, and Black men were vulnerable because they could not protect Black women and were slaughtered when they attempted to, she said.

Fast-forward to 2022 and the “same type of socioeconomic structure exists today as it did then. Black poverty is high. Black unemployment is high. Black folks still are fewer as far as home ownership,” she added.

With that month-to-month struggle for sustenance paired with the lack of options to support people’s needs, “people tend to implode upon each other,” Wilson said.

She said when she thinks about solutions to domestic violence, she thinks about how to detach from the system that wants to manipulate and capitalize on Black people, how to gain deeper knowledge of self and how to create new pathways of life and livelihood.

Some solutions she offered included: tackling poverty and the socioeconomic structure by creating an economy within the Black community and ‘buying Black;’ supporting underfunded grassroots organizations that are grounded in the community; establishing programs and vocational training for children and the community; engaging in agriculture and urban farming; and building infrastructure and offering support services.

Related to the solution on economics, she said Black people must learn to “leverage our allies in support of our goals,” even if those allies aren’t Black. She explained that others could and are willing to give resources, but she is an advocate for Black people setting their own agenda.

Wilson especially noted the importance of mastering self, bringing up Biblical figures like Jesus as examples.

“They had done self-mastery, and they had learned universal law. And they knew how to walk in the world so they could be creative energies,” she said.

She recalled a course she took offered by Dr. Ishmael Tetteh, a spiritual teacher from Ghana, on “soul processing.” Students were asked to make a timeline of their entire lives. Tetteh labeled the painful parts of their lives as “cud,” which is partially digested food that a cow continues to chew on.

“Those painful experiences are like cud in our spirit, and we continue to chew on them. And, he said, the goal of this life/soul processing is to break apart those cud patches and then redefine them in a way that serves you,” Wilson said.

She said as Black people in America, “all of us have trauma” that needs to be unpacked.

Another solution she proposed was creating spaces that are culturally authentic where Black people can heal together. But she said the first step is unpacking the pain that fuels the violence.

“Oftentimes that means you have to move people away from each other so that they can do their own healing,” she said, because “it’s hard to heal with people who have harmed you.”

Necessary infrastructure to her means access to safe houses and community-based intervention.

“If it’s a mom and kids, where do we put them while we work out the situation? And with the man who’s doing it, how do we get them into a situation where they can do some anger management rather than criminalize everything?” she questioned.

When Wilson experienced domestic violence, a woman she had been close to helped her out.

“She talked to me, and she was the person who made space for my healing. She let me stay with her for a while. And so, fast-forward, years go by, I get my act together. And I think about her, and I go back to her and I’m like, ‘I don’t know how to thank you for what you did for me,’” Wilson recalled.

“And she was like, ‘Girl, what you don’t get is that it’s not even about me.’ She’s like, ‘The only reason that I am here to do this for you is because there was some woman who did it for me.’ And she said, ‘So you don’t owe me anything.’” She said, “‘What you owe is you got to step up and do it for someone else when you see a need.’”

Wilson says she lives her life trying to hold true to that advice.

“And I think we have to proceed with that kind of heart in order to really heal people. It can’t just be tactical stuff. It has to be human stuff. It has to be heart stuff,” she said.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

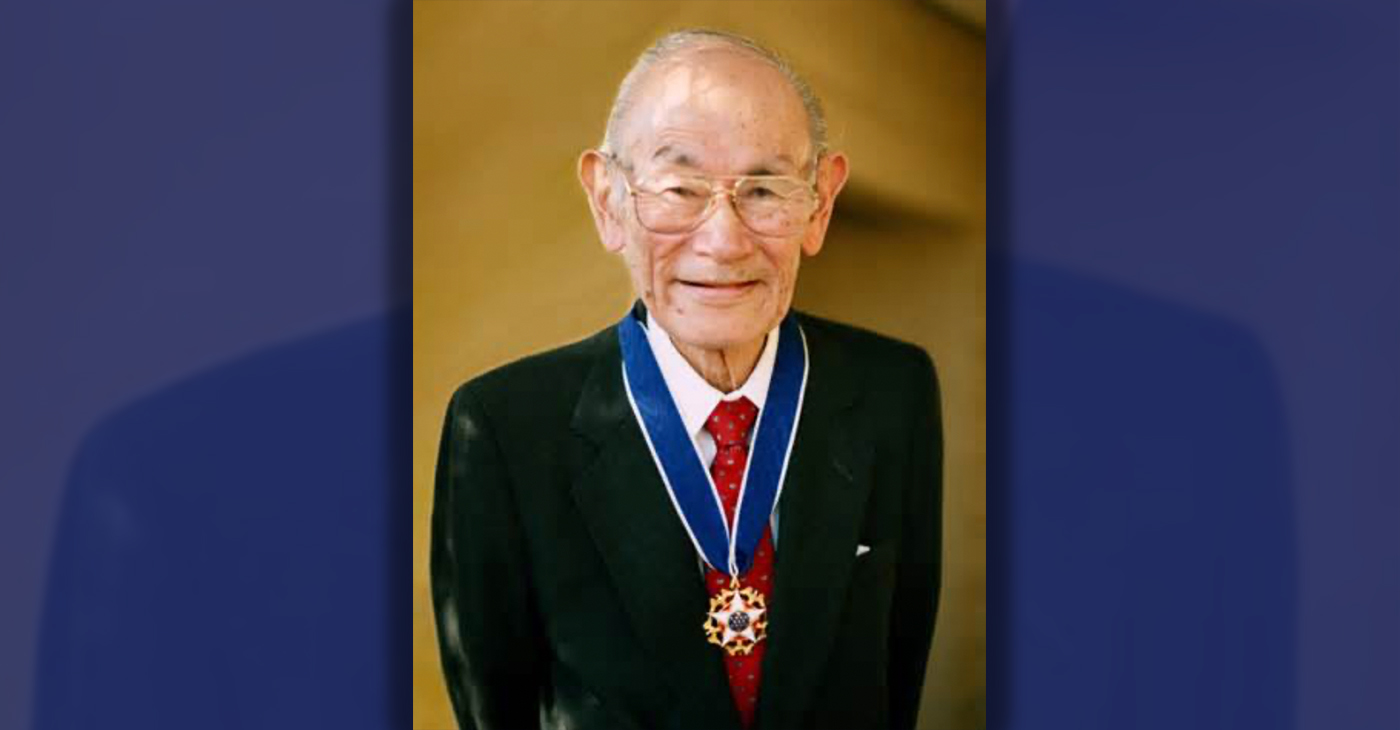

Oakland Schools Honor Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice. His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

By Post Staff

Every Jan. 30, OUSD commemorates the legacy of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native, a Castlemont High School graduate, and a national symbol of resistance, resilience, and justice.

His defiant stand against racial injustice and his unwavering commitment to civil rights continue to inspire the local community and the nation. Tuesday was “Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution” in the state of California and a growing number of states across the country.

One OUSD school is named in his honor: Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy (KDA) elementary in East Oakland.

Several years ago, founding KDA Principal Charles Wilson, in a video interview with anti-hate organization “Not In Our Town,” said, “We chose the name Fred Korematsu because we really felt like the attributes that he showed in his work are things that the children need to learn … that common people can stand up and make differences in a large number of people’s lives.”

Fred Korematsu was born in Oakland on Jan. 30, 1919. His parents ran a floral nursery business, and his upbringing in Oakland shaped his worldview. His belief in the importance of standing up for your rights and the rights of others, regardless of race or background, was the foundation for his activism against racial prejudice and for the rights of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the start of the war, Korematsu was turned away from enlisting in the National Guard and the Coast Guard because of his race. He trained as a welder, working at the docks in Oakland, but was fired after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Fear and prejudice led to federal Executive Order 9066, which forced more than 120,000 Japanese Americans out of their homes and neighborhoods and into remote internment camps.

The 23-year-old Korematsu resisted the order. He underwent cosmetic surgery and assumed a false identity, choosing freedom over unjust imprisonment. His later arrest and conviction sparked a legal battle that would challenge the foundation of civil liberties in America.

Korematsu’s fight culminated in the Supreme Court’s initial ruling against him in 1944. He spent years in a Utah internment camp with his family, followed by time living in Salt Lake City where he was dogged by racism.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford overturned Executive Order 9066. Seven years later, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco vacated Korematsu’s conviction. He said in court, “I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong and do something about it so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color.”

Korematsu’s dedication and determination established him as a national icon of civil rights and social justice. He advocated for justice with Rosa Parks. In 1998, President Bill Clinton gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom saying, “In the long history of our country’s constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls … To that distinguished list, today we add the name of Fred Korematsu.”

After Sept. 11, 2001, Korematsu spoke out against hatred and discrimination, saying what happened to Japanese Americans should not happen to people of Middle Eastern descent.

Korematsu’s roots in Oakland and his education in OUSD are a source of great pride for the city, according to the school district. His most famous quote, which is on the Korematsu elementary school mural, is as relevant now as ever, “If you have the feeling that something is wrong, don’t be afraid to speak up.”

Activism

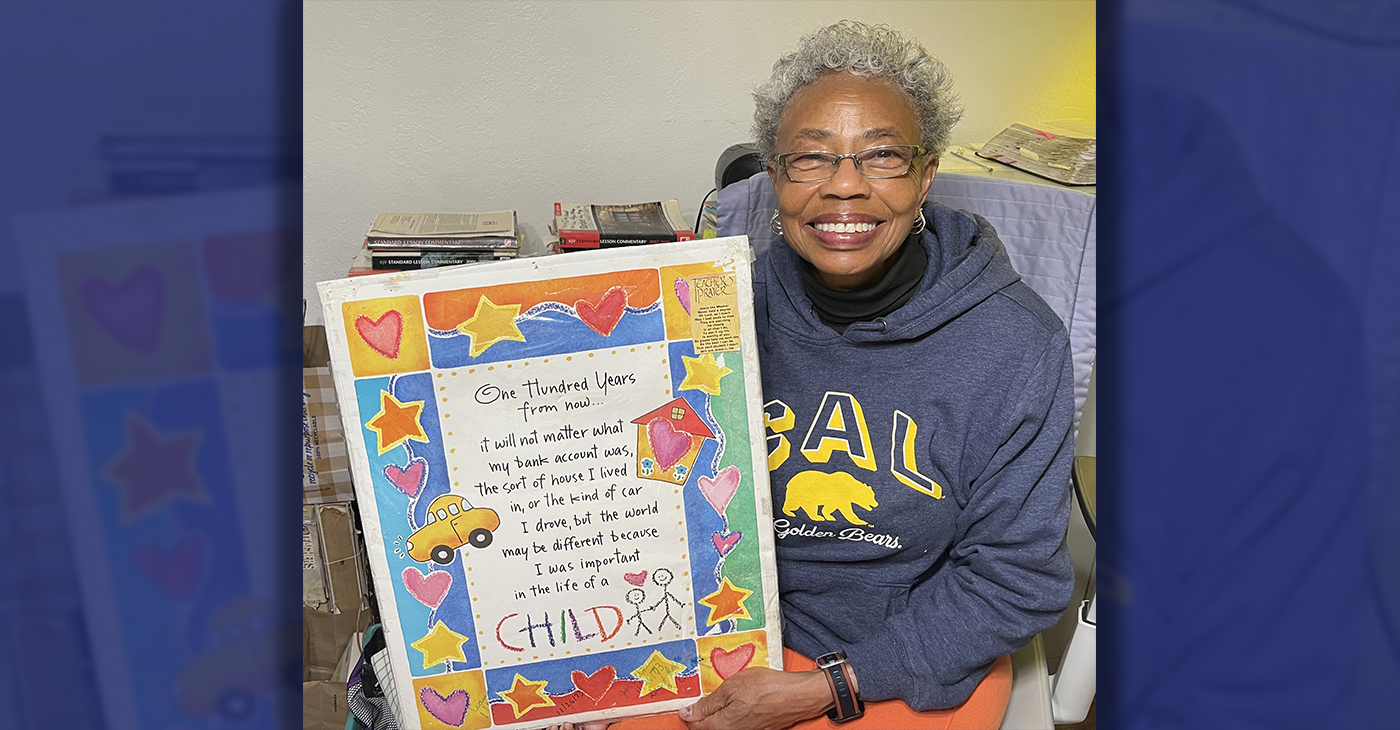

WOMEN IMPACTING THE CHURCH AND COMMUNITY

Juanita Matthews, better known as “Sister Teacher,” is a walking Bible scholar. She moved to California from the great state of Arkansas in 1971. Sister Teacher has a passion for teaching. She has been a member of Bible Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church since 1971.

Sister Juanita Matthews

55 Years with Oakland Public School District

The Teacher, Mother, Community Outreach Champion, And Child of God

Juanita Matthews, better known as “Sister Teacher,” is a walking Bible scholar. She moved to California from the great state of Arkansas in 1971. Sister Teacher has a passion for teaching. She has been a member of Bible Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church since 1971. She followed her passion for teaching, and in 1977 became the lead teacher for Adult Class #6. Her motto still today is “Once My Student, Always My Student”.

Beyond her remarkable love for the Lord, Sister Teacher has showcased her love for teaching by working for the Oakland Unified School District for 55 years, all but four of those years spent at Emerson Elementary and Child Development School. She truly cares about her students, making sure they have the tools/supplies needed to learn either at OUSD or Bible Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church.

She’s also had a “Clothes Closet Ministry” for 51 years, making sure her students have sufficient clothing for school. The Clothes Closet Ministry extends past her students, she has been clothing the community for over 50 years as well. She loves the Lord and is a servant on a mission. She is a loving mother to two beautiful children, Sandra and Andre. This is the impact this woman of God has on her church and the community.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 20 – 26, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoFrom Raids to Revelations: The Dark Turn in Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs’ Saga

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: Lady Day and The Lights!

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBaltimore Key Bridge Catastrophe: A City’s Heartbreak and a Nation’s Alarm

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBaltimore’s Key Bridge Struck by Ship, Collapses into Water