Community

EDSOURCE: California Schools Face ‘Deep Trouble’ as Flooding Danger Looms

As heavy storms keep pounding California with torrential rains and a record Sierra snowpack is poised to melt and send rivers surging over their banks, more than a fifth of the state’s 10,000 K-12 schools are at a high or moderate risk of flooding, an analysis of federal data by EdSource shows.

By Thomas Peele, Emma Gallegos and Daniel J. Willis

EdSource

As heavy storms keep pounding California with torrential rains and a record Sierra snowpack is poised to melt and send rivers surging over their banks, more than a fifth of the state’s 10,000 K-12 schools are at a high or moderate risk of flooding, an analysis of federal data by EdSource shows.

Schools in flood-prone areas, in some cases protected by aging, weakened levees with poor safety ratings, face possible floods similar to those that have already swept through schools in Alameda, Merced and Monterey counties this year, causing millions of dollars in damages, Federal Emergency Management Agency data shows.

Flooding in the Tulare and the San Joaquin basins in the Central Valley in the months ahead “is inevitable,” Jeffrey Mount, a geomorphologist and senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California who studies flood and water management, told EdSource in an interview.

“We’re looking at a pretty epic spring in those places. We’re really going to see some considerable hardship in these small rural communities once this snow begins to melt,” he said. He urged local communities and public agencies like school districts to start planning now.

The snowpack in the southern Sierra measured Monday at more than 300% of what it normally is on April 1 of a given year, according to the state Department of Water Resources. The statewide average came in at 237% of normal.

So much snow has piled atop Alpine County Unified School District’s Bear Valley Elementary School, which sits at 7,000 feet elevation, that it’s been closed over fears the roof may cave in. Its seven students are attending classes at a local library.

“The fact is there is quite a lot of water in the water cannon that is pointed west in the Sierra. And these storms just keep loading it up,” Mount said.

Tulare County in the southern Central Valley, where flooding caused by breached levees soaked the unincorporated towns of Allensworth and Alpaugh last month, has the most schools in the state classified at high flood risk — 35 — according to FEMA data that was last updated in 2009.

Mount specifically singled out the cities of Visalia in Tulare County and Firebaugh and Mendota in western Fresno County as places that should expect to be hit hard.

“Mendota, Firebaugh, places like that are on the San Joaquin River and have schools within them, they’re in deep trouble,” Mount said.

Data show all six schools in the Firebaugh-Las Deltas Unified School District are at high risk of flooding. Levees in the area have a safety rating of unsatisfactory, State Department of Water Resources records show. Those levees, built to prevent the overflow of rivers, are “in pretty bad shape. They’ve been severely neglected over the last 100 years, certainly in the last 50 years,” Mount said.

The school district is preparing staff, students and their families for the serious possibility of a flood. Superintendent Roy Mendiola has encouraged families and staff to prepare a “go bag” with their most important documents. In the event of an evacuation, students will be shuttled to a produce warehouse on high ground on the other side of town. The school district has the largest fleet of buses and vans in the region, so it also plans to help evacuate local residents.

Local agencies, including the city of Firebaugh and its police department, have been key partners in preparing for a potential disaster. Mendiola is getting more guidance from officials at Planada Elementary School District across the valley, which was recently damaged by flooding. But the state hasn’t stepped up with any sort of guidance about how to prepare, said Mendiola. Rather, he’s gotten emails about how to deal with damage in the aftermath of storms. “It wasn’t so much, ‘Here’s what you could do to prepare a plan for an emergency like that,'” said Mendiola.

In Tulare County on the eastern side of the valley, Visalia Unified School District, 38 of 42 schools are at high or moderate flooding danger, data show. Ten are at high risk. A district spokesperson, Cristina Gutierrez, declined to make officials available for an interview. In an email, she wrote that the district is in “constant touch” with Visalia city officials and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which monitors river levels.

Tulare County Superintendent of Schools Tim Hire said school officials in the county are “carefully watching and making decisions day by day” about how to proceed. “They all want students in the classroom, but only if it is safe.”

There is no question that floods will come, said Carlos Molina, a meteorologist for the National Weather Service in Hanford.

Melting snow will create double the amount of water leaving the mountains than reservoirs from Yosemite in the north to Lake Isabella in the south can hold at one time, he said.

Which rivers will flood? “Take your pick,” Molina said, rattling off names: The Kern. The King. The San Joaquin.

“They will be having problems from now until later this summer.”

The Pajaro flood

When a 75-year-old levee holding back the Pajaro River from the unincorporated northern Monterey County community of Pajaro ruptured March 11, floodwater poured into the center of the farming town. Homes, businesses, and Pajaro Middle School stood in its path. Water entered the school’s classrooms and submerged its grounds.

When State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond visited the school on March 24 some classrooms remained wet. Mud caked walkways inside and out.

Members of Thurmond’s staff wore knee boots as they toured the building. Pajaro Unified School District Superintendent Michelle Rodriguez said cleanup hadn’t started because insurance adjusters hadn’t completed their work. At that point, it was nearly two weeks since the flood and there were concerns mold would worsen the damage. Thurmond, standing before television cameras, called an executive of the school’s insurance company and left a voicemail urging the claim be expedited.

While praising relief workers and expressing concern for displaced families, at one point making a recorded statement to them in Spanish, Thurmond, a former member of the state Assembly, appeared to lack basic knowledge about the situation.

Asked at a news conference how many other schools in the state were prone to similar flooding as Pajaro Middle, he didn’t provide a number. Thurmond responded by describing the many threats schools face. “Before we were talking about floods, we were talking about wildfires, power-safety shut-offs and, of course, we’re still overcoming the impacts of a pandemic. Sadly, it’s become the new normal for there to be school disruption.”

In an email, Scott Roark, spokesperson, said the state Department of Education is in regular communication with other state agencies and the National Weather Service about school flooding risks.

The department recently alerted 500 districts on preparing for and dealing with flood hazards based on models developed by the state’s Department of Water Resources. The information was distributed through local county offices of education, said Abel Guillen, deputy superintendent of public instruction. Many schools on that list are in the Tulare Basin, which includes both Tulare and Kings counties. Schools on those lists are encouraged to update their emergency plans, check to see that they have flood insurance, inventory and photograph costly equipment, move computers from low-lying areas, begin sandbagging and strengthen contact with local emergency operations.

Overall, the FEMA data shows flood ratings for 10,628 California schools, some of them in shared buildings. Of those, 2,230 are identified with high or moderate flood risk. Of those, 398 are high risk of flooding. Another 383 are listed as having a possible flood risk, but there is not enough information to make a more exact estimate.

The risk to another 56 schools is listed as unknown because they are not covered in FEMA flood maps. All are in Alpine, Sutter and Yuma Counties. There are 7,958 schools identified as low-risk. In only three of the state’s 58 counties are all schools listed as low risk— Amador, Calaveras and San Francisco.

Data shows that some of the schools rated as high risk were built in floodways, or floodplains, or in locations where floodwaters are likely to pool. Others were built where floodwater is expected to flow across school grounds.

Of schools rated at moderate or high risk, data show 602 are marked as being at reduced risk because levees protect them. Most are in urban areas — nearly half are in Los Angeles and Orange counties.

In Pajaro, the middle school is listed by FEMA as being at high risk for flooding and being in a sheeting area where water would flow over the school property. That’s what happened when the nearby levee, which was built in 1949, breached March 11.

The flood was the fourth time the town flooded since then and local officials are bitterly complaining about a lack of maintenance on the levee. The river divides Monterey and Santa Cruz counties. The Mercury News reported March 26 that Santa Cruz County spent five times more money than Monterey County did on maintaining the levee on its side of the river over the past three years. The levee breached when the river was below flood stage.

When the record snowmelt hits rivers in the months ahead the state’s levees will be severely tested, said Farshid Vahedifard, a Mississippi State University engineering professor who has extensively studied California’s system of more than 21,000 kilometers of urban and nonurban levees. Many, he said, are aging earthen berms not meant to serve as critical infrastructure.

“I won’t be surprised if I see more failures,” he told EdSource.

Mount put it succinctly: “There are only two kinds of levees,” he said. “Those that have failed and those that will fail.”

They will be severely tested around Memorial Day, Mount said, as snowmelt overwhelms the water systems just when schools are letting out at the end of the academic year and preparing for summer sessions. The ability to use schools as emergency shelters and rally points could be impeded.

In the Southern Sierra, Mount predicted, the looming disaster is “going to last months and, it may take years to recover from.”

The filthiest water imaginable

When heavy rains on Jan. 9 caused a stream to flood and a levee to break in Planada, an unincorporated Merced County community, water naturally ran to the lowest points in town — including the grounds of Planada Elementary School built in 1955 below flood level. FEMA lists the school as a high flood risk and a “special flood hazard area” where water will pond with nowhere to go.

“The filthiest water imaginable” flooded the school, said Jose Gonzalez, superintendent of the Planada Elementary School District. “There were porta-potties floating throughout the community. There were dead rodents.”

Twenty-six first- through fifth-grade classrooms were lost. So were 4,000 books. Rebuild costs, including raising the site above the floodplain, is roughly $12 million. There’s no date for work to start.

School was closed for eight days until students could attend classes in another school in town that didn’t flood.

The floodwaters came fast, Gonzalez said. But it happened when school was closed. Had the same conditions occurred on a school day, “It would have been complete chaos,” he said.

The disaster wasn’t new for Gonzalez. The school also flooded during a 2018 storm.

“They said (2018) was a 100-year flood,” Gonzalez said. Federal and state officials told him,'”Don’t worry, it’s not going to happen again,”‘ he said. “Five years later here we are.”

In 2018 the district didn’t have flood insurance. But it was able to join a joint-powers authority of other small districts to buy insurance that covered the January damage. Litigation over the levee breach is likely, he said.

The district has a soccer field and track nearby. Gonzalez said it may be lowered “with the field at the bottom with the track around the top” to serve as a “ponding basin” where floodwater could be diverted. He’s had to learn about water rights, hydraulics and meteorology — things “they don’t teach you in superintendents’ school.”

“Any time there’s a light rain I drive out to check the creek,” he said. “It’s just part of the routine.”

For decades schools in California could be built anywhere where a local district could find and afford land. If that means in the floodplain of the Pajaro River or the lowlands of Planada, then that’s where they were built.

“Finding land for new schools isn’t easy. It’s only getting harder as the cost of land increases,” said Jeffrey Vincent, of UC Berkeley’s Center for Cities & Schools. “It’s not like they get the pick of the litter.”

School boards can override other local agencies on land use decisions, putting schools wherever they can acquire land.

But one district in 2018 decided not to build in a floodplain.

The Kern High School District declined to build a new school in a floodplain to serve the unincorporated town of Lamont, said Jack “Woody” Colvard, a facilities management consultant for the Kern County superintendent of schools. He previously worked for the Kern High School District, which considered several options that would allow the school to be built in Lamont, but none of them were practical.

One idea was to buy 180 acres for a 120-acre campus — the other 60 acres would provide dirt that would allow the campus to be raised above the floodplain. Just the grading alone on a project like that would run $5 million. It also considered building canals that would allow floodwaters to move around the school, Colvard said.

These options would turn the school into an “island.” That’s a problem because schools shouldn’t merely be safe in an emergency, Colvard said, they should also be accessible places for the community to find food, water and other crucial resources at such times.

Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi, D-Torrance, notes that the state treats schools as the “backbone” of emergency response efforts in the event of an earthquake. As the Legislature crafts another state bond measure for school facilities, there have been discussions about how California can also prepare school facilities for the effects of climate changes that have increased the risk of wildfires, heat waves and flooding.

“We’ve been having ongoing discussions about how the bond should acknowledge the realities of climate change,” he said.

One provision that may be added to the bond measure would authorize the state to acquire portable classrooms so that schools can have them quickly in the event of a disaster.

But even a school labeled by FEMA to be a low flooding risk has suffered from a recent major flood.

The tiny Sunol Glenn Unified School District nestled in the hills of eastern Alameda County has one school. A stream, Sinbad Creek runs behind it. Superintendent Molleen Barnes said she never really gave the creek much thought, other than asking local officials to clear out some branches that had gotten stuck under a nearby bridge that passed over it.

The creek usually “ran at a trickle” at a depth of 15 to 17 inches, she said.

Then the night of Dec. 31 and into New Year’s Day, Barnes started getting texts from parents telling her the school grounds were flooding. As an atmospheric river unleashed torrential rains, Sinbad Creek had jumped its banks, surging to 24 feet. The branches under the bridge hadn’t been cleaned out.

“Of course, we’d been in a drought and this hadn’t been on our radar,” Barnes told EdSource. When the water receded the school grounds were covered in 18 inches of mud. Three modular classrooms were knocked off their foundations. Fences toppled. A classroom and an office were damaged. The entire building had to be assessed for mold.

The district didn’t have flood insurance. The damage was estimated at about $1.8 million, Barnes said.

“The school’s 100 years old and it never flooded, “Barnes said. “This isn’t something we’d even thought about.

“Until now.”

Alameda County

DA Pamela Price Stands by Mom Who Lost Son to Gun Violence in Oakland

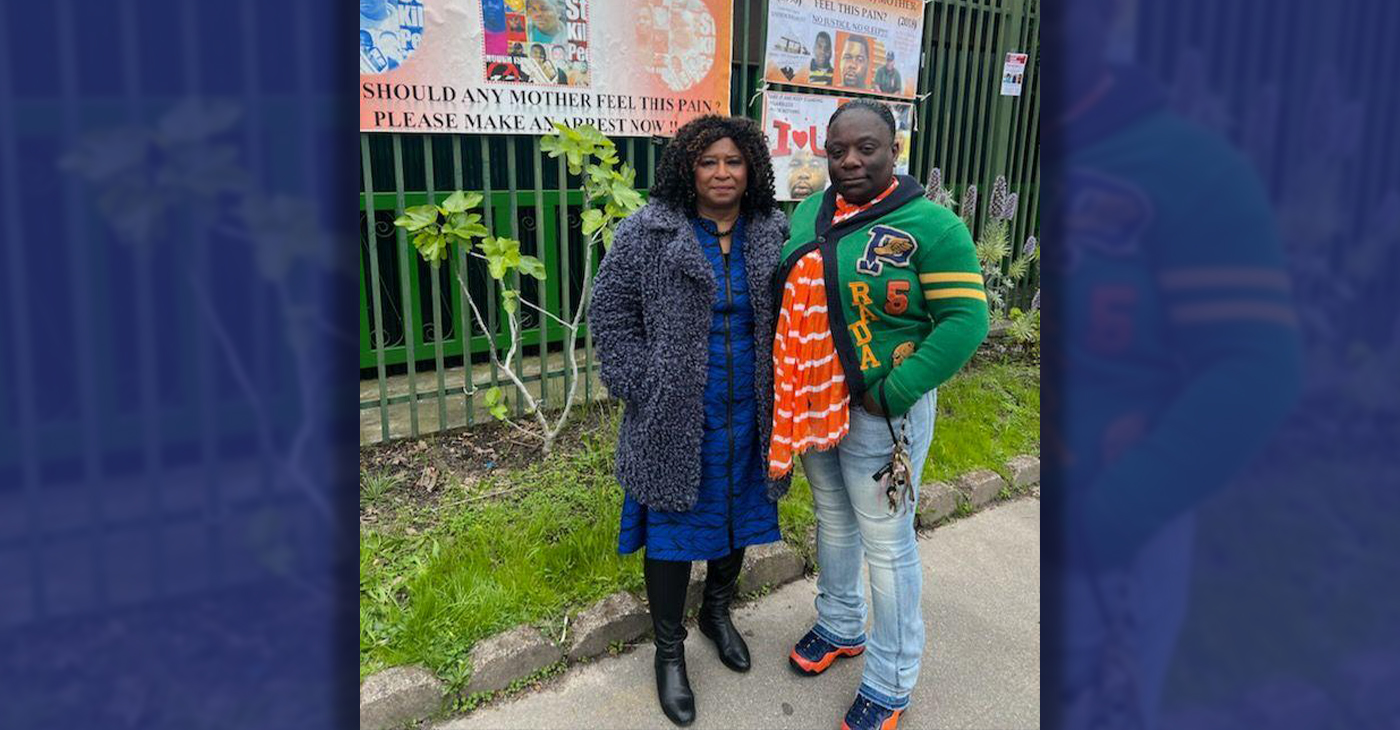

Last week, The Post published a photo showing Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price with Carol Jones, whose son, Patrick DeMarco Scott, was gunned down by an unknown assailant in 2018.

Publisher’s note: Last week, The Post published a photo showing Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price with Carol Jones, whose son, Patrick DeMarco Scott, was gunned down by an unknown assailant in 2018. The photo was too small for readers to see where the women were and what they were doing. Here we show Price and Jones as they complete a walk in memory of Scott. For more information and to contribute, please contact Carol Jones at 510-978-5517 at morefoundation.help@gmail.com. Courtesy photo.

City Government

Vallejo Welcomes Interim City Manager Beverli Marshall

At Tuesday night’s Council meeting, the Vallejo City Council appointed Beverli Marshall as the interim city manager. Her tenure in the City Manager’s Office began today, Wednesday, April 10. Mayor Robert McConnell praised Marshall’s extensive background, noting her “wide breadth of experience in many areas that will assist the City and its citizens in understanding the complexity of the many issues that must be solved” in Vallejo.

Special to The Post

At Tuesday night’s Council meeting, the Vallejo City Council appointed Beverli Marshall as the interim city manager. Her tenure in the City Manager’s Office began today, Wednesday, April 10.

Mayor Robert McConnell praised Marshall’s extensive background, noting her “wide breadth of experience in many areas that will assist the City and its citizens in understanding the complexity of the many issues that must be solved” in Vallejo.

Current City Manager Michael Malone, whose official departure is slated for April 18, expressed his well wishes. “I wish the City of Vallejo and Interim City Manager Marshall all the best in moving forward on the progress we’ve made to improve service to residents.” Malone expressed his hope that the staff and Council will work closely with ICM Marshall to “ensure success and prosperity for the City.”

According to the Vallejo Sun, Malone stepped into the role of interim city manager in 2021 and became permanent in 2022. Previously, Malone served as the city’s water director and decided to retire from city service e at the end of his contract which is April 18.

“I hope the excellent work of City staff will continue for years to come in Vallejo,” he said. “However, recent developments have led me to this decision to announce my retirement.”

When Malone was appointed, Vallejo was awash in scandals involving the housing division and the police department. A third of the city’s jobs went unfilled during most of his tenure, making for a rocky road for getting things done, the Vallejo Sun reported.

At last night’s council meeting, McConnell explained the selection process, highlighting the council’s confidence in achieving positive outcomes through a collaborative effort, and said this afternoon, “The Council is confident that by working closely together, positive results will be obtained.”

While the search for a permanent city manager is ongoing, an announcement is expected in the coming months.

On behalf of the City Council, Mayor McConnell extended gratitude to the staff, citizen groups, and recruitment firm.

“The Council wishes to thank the staff, the citizens’ group, and the recruitment firm for their diligent work and careful consideration for the selection of what is possibly the most important decision a Council can make on behalf of the betterment of our City,” McConnell said.

The Vallejo Sun contributed to this report.

City Government

Vallejo Community Members Appeal Major Use Permit for ELITE Charter School Expansion

Vallejo community members, former Solano County judge Paul Beeman and his wife Donna Beeman, filed an appeal against the approval of the Major Use Permit for the expansion of ELITE Public Schools into downtown less than two weeks after the Planning Commission approved the permit with a 6-1 vote.

By Magaly Muñoz

Vallejo community members, former Solano County judge Paul Beeman and his wife Donna Beeman, filed an appeal against the approval of the Major Use Permit for the expansion of ELITE Public Schools into downtown less than two weeks after the Planning Commission approved the permit with a 6-1 vote.

ELITE Charter School has been attempting to move into the downtown Vallejo area at 241-255 Georgia Street for two years, aiming to increase its capacity for high school students. However, a small group of residents and business owners, most notably the Beeman’s, have opposed the move.

The former county judge and his wife’s appeal alleges inaccuracies in the city’s staff report and presentation, and concerns about the project’s exemption from the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

The Beeman’s stress that their opposition is not based on the charter or the people associated with it but solely on land use issues and potential impact on their business, which is located directly next to the proposed school location.

The couple have been vocal in their opposition to the expansion charter school with records of this going back to spring of last year, stating that the arrival of the 400 students in downtown will create a nuisance to those in the area.

During the Planning Commission meeting, Mr. Beeman asked Commissioner Cohen-Thompson to recuse herself from voting citing a possible conflict of interest because she had voted to approve the school’s expansion as trustee of the Solano County Board of Education. However, Cohen-Thompson and City Attorney Laura Zagaroli maintained that her positions did not create a conflict.

“I feel 100% that the attorney’s opinion is wrong,” Beeman told the Post.

He believes that Cohen-Thompson has a vested interest in upholding her earlier vote as a trustee and is advocating for people to ratify her opinion.

Cohen-Thompson declined to comment on the Post’s story and Zagaroli did not respond for comment.

The Beeman’s further argue that the school’s presence in the commercial district could deter future businesses, including those who sell alcohol due to proximity to schools.

According to Alcohol Beverage Control (ABC), the department can deny any retail license located within 600 feet of a school. Only one alcohol selling business is located within that range, which is Bambino’s Italian restaurant at 300 feet from the proposed location.

The project’s proponents argue that the school would not affect current or future liquor-selling establishments as long as they follow the ABC agency’s guidelines.

The Beeman’s also referenced Vallejo’s General Plan 2040, stating that the proposed expansion does not align with the plan’s revitalization efforts or arts and entertainment use. They argue that such a development should focus on vacant and underutilized areas, in accordance with the plan.

The proposed location, 241 Georgia Street aligns with this plan and is a two minute walk from the Vallejo Transit Center.

The General Plan emphasizes activating the downtown with, “Workers, residents, and students activate the downtown area seven days a week, providing a critical mass to support a ‘cafe culture’ and technology access, sparking innovation and entrepreneurship.”

City staff recommended exempting the project from CEQA, citing negligible impacts. However, Beeman raised concerns about increased foot traffic potentially exacerbating existing issues like theft and the lack of police presence downtown. He shared that he’s had a few encounters with kids running around his office building and disturbing his work.

Tara Beasley-Stansberry, a Planning Commissioner and owner of Noonie’s Place, told the Post that the arrival of students in downtown can mean not only opportunities for surrounding businesses, but can allow for students to find their first jobs and continue to give back to the community in revitalization efforts.

Beasley-Stansberry had advocated for the students at the March Commission meeting, sharing disappointment in the way that community members spoke negatively of the teens.

“To characterize these children as criminals before they’ve even graduated from high school, that’s when I had to really take a look and I was kind of lost as to where we were as a city and as a community to where I couldn’t understand how we were viewing these children,” Beasley-Stansberry told the Post.

She added that the commissioners who voted yes on the project location have to do what is right for the community and that the city’s purpose is not all about generating businesses.

ELITE CEO Dr. Ramona Bishop, told the Post that they have worked with the city and responded to all questions and concerns from the appropriate departments. She claimed ELITE has one of the fastest growing schools in the county with mostly Vallejo residents.

“We have motivated college-bound high school students who deserve this downtown location designed just for them,” Bishop said. “We look forward to occupying our new [location] in the fall of 2024 and ask the Vallejo City Council to uphold their Planning Commission vote without delay.”

The Vallejo City Council will make the final decision about the project location and Major Use Permit on April 23.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024