Black History

Before Chocolate Cities: The New Promised Land

During the late 19th and 20th centuries, at least 88 and as many as 200 Black towns were established throughout the United States. Mostly or completely Black incorporated communities with autonomous Black city governments and commercially oriented economies, these cities were created with purposeful economic and political motives.

By Tamara Shiloh

During the late 19th and 20th centuries, at least 88 and as many as 200 Black towns were established throughout the United States. Mostly or completely Black incorporated communities with autonomous Black city governments and commercially oriented economies, these cities were created with purposeful economic and political motives.

The greatest draw to these cities was the ability to escape racial oppression, control one’s economic destiny, and prove Black capacity for self-government. They were thought to be the New Promised Land. Texas would lead the effort with the founding of Shankleville Community (1867) and Kendleton (1870), both populated by ex-slaves from the surrounding countryside.

At the end of the Reconstruction-era South, Nicodemus, Kansas, (1877) was founded by newly freed slaves.

The land on which Nicodemus and other Black communities in Kansas stood turned out to be unproductive for agriculture. Natural drought cycles diminished efforts to raise crops. Despite this setback, the lifestyle remained better than that of the South. Instead, residents built houses, businesses, clubs, churches, and schools. They also “participated in political and commercial life in ways previously denied to them,” according to the National Park Service website.

Nicodemus, populated with some descendants of the original settlers, still stands. The 2020 census reported its population to be 14.

On June 30, 1908, Allen Allensworth, a former soldier, and William Payne, a teacher, created the California Colony and Home Promoting Association. It was soon dubbed Allensworth. It had a depot station on the main Santa Fe Railroad line from Los Angeles to San Francisco, the soil was fertile, the water seemingly abundant, and the acreage was plentiful and reasonably priced, according to the News One website.

The town became a member of the county school district and the regional library system. There, the first Black Justice of the Peace in post-Mexican California was elected. By 1914, it boasted 100 residents. Most of the adults worked 10-acre farms nearby, which they purchased for $110 per acre on an installment plan.

Allen Allensworth, in 1914, lobbied for an educational institute. That’s when a series of methodical racist acts began to trigger the community’s decline. The Santa Fe Railroad built a spur line to neighboring Alpaugh, depriving Allensworth of its lucrative carrying trade. Santa Fe also refused to hire Blacks as managers or ticket agents of the station located in the colony despite repeated letters and recriminations.

Powerful white farmers diverted the White River to irrigate their own crops and cut off Allensworth’s supply. The Pacific Farming Company then failed to honor its commitment to supply sufficient water for irrigation. But the largest factor in the community’s decline was Allen Allensworth’s death. By 1920, people began to leave the area.

On Oct. 6, 1976, what was once a thriving Black community was dedicated as a park.

Read more about the dynamic network of cities and towns built, maintained, and defended by African Americans in “Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life,” by Marcus Anthony Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 17 – 23, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Black History

Matthew Henson: Explorer Extraordinaire

Matthew Henson, a trailblazing explorer who overcame countless obstacles to leave an incredible mark on history. Born on August 8, 1866, in Charles County, Maryland, his journey is a testament to the power of determination and the spirit of adventure.

By Tamara Shiloh

Matthew Henson, a trailblazing explorer who overcame countless obstacles to leave an incredible mark on history. Born on August 8, 1866, in Charles County, Maryland, his journey is a testament to the power of determination and the spirit of adventure.

Henson’s life began amidst the backdrop of post-Civil War America, where opportunities for African Americans were scarce. From a young age, he possessed an insatiable curiosity about the world beyond his small town. At the age of 12, he embarked on a journey that would change the course of his life forever when he joined a merchant ship as a cabin boy.

His most famous expedition was his journey to the Arctic with renowned explorer Robert E. Peary. In 1887, Henson joined Peary’s crew as a seaman and quickly proved himself to be invaluable with his skills as a navigator and craftsman. Over the course of several expeditions, Matthew endured extreme cold, treacherous terrain, and grueling conditions as he and Peary sought to reach the elusive North Pole.

In 1908–09, Peary set out on his eighth attempt to reach the North Pole. It was a big expedition, with Peary planning to leave supplies along the way. When he and Henson boarded their ship, the Roosevelt, leaving Greenland on August 18, 1909, they were joined by a large group. This included 22 Inuit men, 17 Inuit women, 10 children, 246 dogs, 70 tons of whale meat, blubber from 50 walruses, hunting gear, and tons of coal.

In February, Henson and Peary left their anchored ship at Ellesmere Island’s Cape Sheridan, along with the Inuit men and 130 dogs. They worked together to set up a trail and supplies along the way to the Pole.

Peary picked Henson and four Inuit people to join him in the final push to the Pole. However, before they reached their destination, Peary couldn’t walk anymore and had to ride in a dog sled. He sent Henson ahead to scout the way. In a later interview with a newspaper, Henson recalled being in the lead and realizing they had gone too far. The group turned back, and Henson noticed his footprints helped guide them to their destination. At that location, Henson planted the American flag.

Henson’s legacy extends far beyond his expeditions to the Arctic. He shattered racial barriers in the world of exploration and inspired countless individuals, regardless of race, to dream big and pursue their passions. In 1937, he was finally recognized for his achievements when he was inducted into The Explorers Club, an organization dedicated to promoting scientific exploration and field research.

Matthew Henson died in the Bronx, New York, on March 9, 1955, at the age of 88.

Art

Marin County: A Snapshot of California’s Black History Is on Display

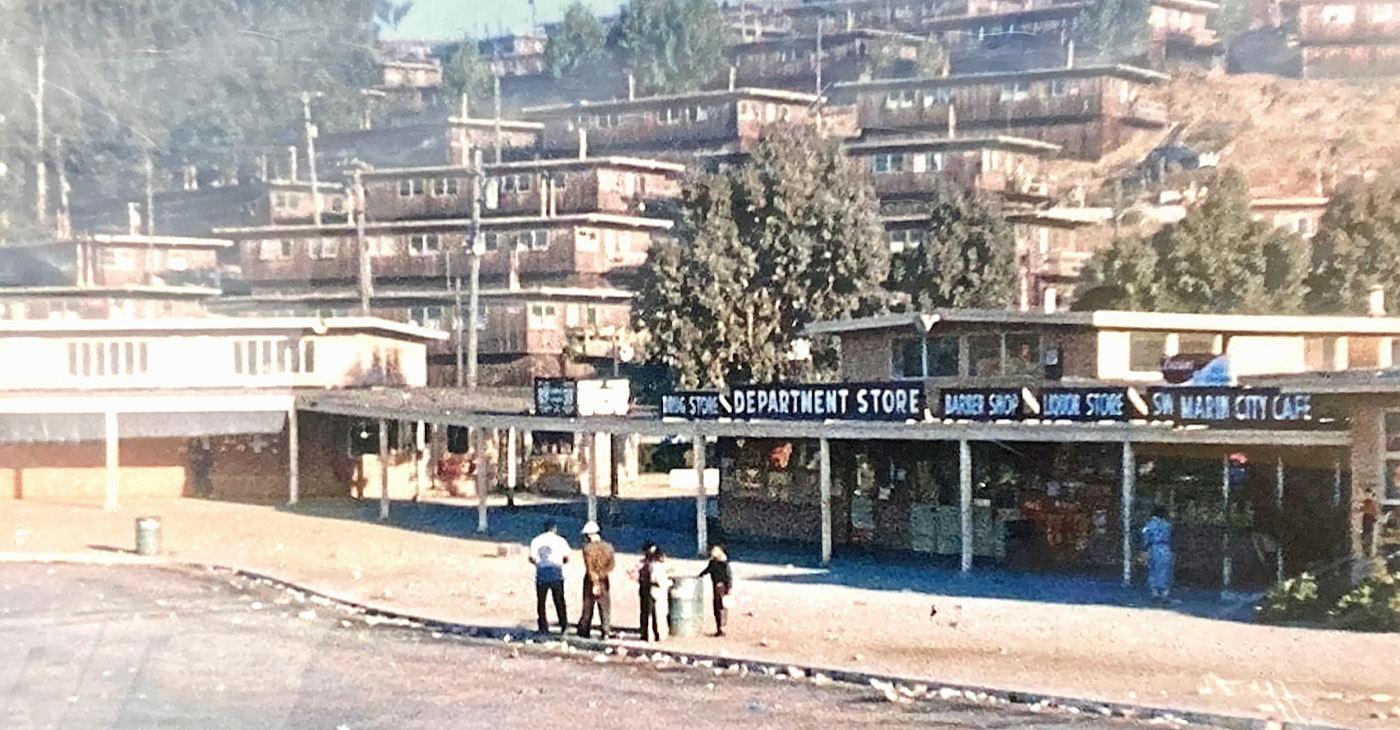

The Marin County Office of Education, located at 1111 Las Gallinas Ave in San Rafael, will host the extraordinary exhibit, “The Legacy of Marin City: A California Black History Story (1942-1960),” from Feb. 1 to May 31, 2024. The interactive, historical, and immersive exhibit featuring memorabilia from Black shipyard workers who migrated from the South to the West Coast to work at the Marinship shipyard will provide an enriching experience for students and school staff. Community organizations will also be invited to tour the exhibit.

By Post Staff

The Marin County Office of Education, located at 1111 Las Gallinas Ave in San Rafael, will host the extraordinary exhibit, “The Legacy of Marin City: A California Black History Story (1942-1960),” from Feb. 1 to May 31, 2024.

The interactive, historical, and immersive exhibit featuring memorabilia from Black shipyard workers who migrated from the South to the West Coast to work at the Marinship shipyard will provide an enriching experience for students and school staff. Community organizations will also be invited to tour the exhibit.

All will have the opportunity to visit and be guided by its curator Felecia Gaston.

The exhibit will include photographs, articles and artifacts about the Black experience in Marin City from 1942 to 1960 from the Felecia Gaston Collection, the Anne T. Kent California Room Collection, The Ruth Marion and Pirkle Jones Collection, The Bancroft Library, and the Daniel Ruark Collection.

It also features contemporary original artwork by Chuck D of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame group Public Enemy, clay sculptures by San Francisco-based artist Kaytea Petro, and art pieces made by Marin City youth in collaboration with Lynn Sondag, Associate Professor of Art at Dominican University of California.

The exhibit explores how Marin City residents endured housing inequities over the years and captures the history of plans to remove Black residents from the area after World War II. Throughout, it embodies the spirit of survival and endurance that emboldened the people who made Marin City home.

Felecia Gaston is the author of the commemorative book, ‘A Brand New Start…This is Home: The Story of World War II Marinship and the Legacy of Marin City.’ Thanks to the generous contribution of benefactors, a set of Felecia’s book will be placed in every public elementary, middle, and high school library in Marin.

In addition, educators and librarians at each school will have the opportunity to engage with Felecia in a review of best practices for utilizing the valuable primary sources within the book.

“Our goal is to provide students with the opportunity to learn from these significant and historical contributions to Marin County, California, and the United States,” said John Carroll, Marin County Superintendent of Schools.

“By engaging with Felecia’s book and then visiting the exhibit, students will be able to further connect their knowledge and gain a deeper understanding of this significant historical period,” Carroll continued.

Felecia Gaston adds, “The Marin County Office of Education’s decision to bring the Marin City Historical Traveling Exhibit and publication, ‘A Brand New Start…This is Home’ to young students is intentional and plays a substantial role in the educational world. It is imperative that our community knows the contributions of Marin City Black residents to Marin County. Our youth are best placed to lead this transformation.”

The Marin County Office of Education will host an Open House Reception of the exhibit’s debut on Feb. 1 from 4 p.m. – 6 p.m.. All school staff, educators, librarians, and community members are encouraged to attend to preview the exhibit and connect with Felecia Gaston. To contact Gaston, email MarinCityLegacy@marinschools.org

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 27 – April 2, 2024

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: D.C. Crime Bill Fails to Address Root Causes of Violence and Incarceration

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoMayor, City Council President React to May 31 Closing of Birmingham-Southern College

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoBeloved Actor and Activist Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. Dies at 87

-

Community1 week ago

Community1 week agoFinancial Assistance Bill for Descendants of Enslaved Persons to Help Them Purchase, Own, or Maintain a Home

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 3 – 6, 2024

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoV.P. Kamala Harris: Americans With Criminal Records Will Soon Be Eligible for SBA Loans

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 10 – 16, 2024