#NNPA BlackPress

“Recovering Untold Stories”: Civil Rights Veteran Revisits School Victory

NNPA NEWSWIRE — Bennie and Plummie Richburg Parson, along with Harry and Eliza Briggs, parents of five schoolchildren, were the first signers of the 1949 petition for “equal educational opportunities and facilities.” Although “Briggs v. Elliott” was the first of the school desegregation cases to reach the court, it was placed behind the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education case, possibly because of the maneuvering of South Carolina Gov. James Byrnes. On May 17, 1954, the Parsons family, the Briggs family, and dozens of other unflinching South Carolinians were vindicated with the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision ruling segregation unconstitutional.

By Christopher Frear, Center for Civil Rights History and Research

COLUMBIA, S.C. — As a child in South Carolina after World War Two, Celestine Parson Lloyd took part in a groundbreaking study to fight school segregation, a fight her parents and NAACP lawyers carried to victory in the U.S. Supreme Court.

On Jan. 15, Ms. Parson Lloyd, now of Mount Vernon, New York, relived a moment of that fight—and the victory—as part of the public panel “Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision” organized by the University of South Carolina Center for Civil Rights History and Research and the South Carolina African American Heritage Commission.

“I heard Harold Boulware, Thurgood Marshall, all the NAACP lawyers,” at the strategy meetings, she said.

Ms. Parson Lloyd described vivid memories of seeing Ku Klux Klan fliers posted on their front door and of visiting the burned-out home of Clarendon County movement leader, the Rev. J. A. De Laine.

Celestine Parson Lloyd

In building the legal case, pioneering psychologists Drs. Kenneth and Mamie Clark conducted a now-famous doll test with Summerton school children, including Ms. Parson Lloyd. They asked children which doll they liked better between a white doll and black doll and which one was the “good” one and the “bad” one to test the effects of segregation on children. Ms. Parson Lloyd recalled clearly that she had selected the African American doll.

“I knew it had something to do with the case,” she recalled. “As long as I knew it was something pertaining to the case, I would participate.”

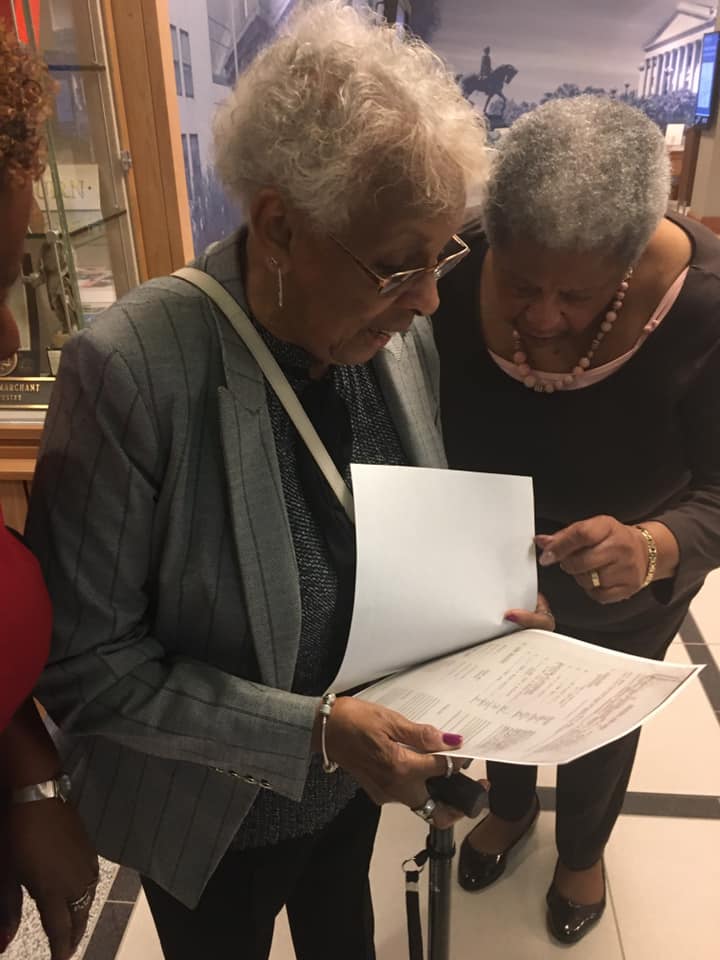

After the panel discussion, researchers with the Center for Civil Rights presented Ms. Parson Lloyd with a copy of her test results from February 24, 1951, that they had uncovered during a visit to the Library of Congress.

“It brought back memories,” she said later. “I was elated. My parents, along with me, contributed to something so meaningful. It was important stuff for our society.”

At the panel, Ms. Parson Lloyd shared her detailed and sometimes harrowing memories of the desegregation struggle in Summerton.

In defiance of known threats, her parents, Bennie and Plummie Richburg Parson, agreed that her father should sign a petition championing the end of racial segregation in schools.

“Don’t take your name off the petition, even if you have to eat dirt,” her grandfather told her father as young Celestine listened. And her great-grandmother Angeline Brunson Parson, who lived to the age of 117, told stories of her life in enslavement and of emancipation.

“One night, my father wasn’t home,” Mrs. Parson Lloyd recalled, “and they came and they knocked on the door, and they said, ‘We were looking for this little lost boy,’ but that’s what they called men in the South, a boy. What they were doing was taking people out and they beat you and they mugged you and leave you somewhere, and if my father was home, he would have been taken out and probably beaten and left some place.

“And I was petrified. We were all afraid, because we didn’t know what was going to be the next day,” she told the panel audience.

The legal effort started with NAACP support in 1948, when Levi Pearson initiated a lawsuit against the Summerton School District to provide a school bus for his children. On a property line technicality, Pearson had to withdraw as the plaintiff and a new lawsuit had to be built with parents of Scott’s Branch School students.

At meetings in St. Mark and Liberty Hill AME churches in Summerton, Ms. Parson Lloyd listened intently as NAACP officers and lawyers explained the lawsuit and counseled parents about the violent response ahead. She is featured in several photographs taken of plaintiffs at local churches and now archived in University of South Carolina collections.

Along with the Parsons, Harry and Eliza Briggs, parents of five schoolchildren, were the first signers of the 1949 petition for “equal educational opportunities and facilities.” The signers refused to yield to violence, even when Harry Briggs was fired from his job and the De Laine family home was burned to the ground. Thurgood Marshall, Robert Carter and South Carolina’s Harold Boulware filed Briggs v. Elliott in federal court, directly challenging segregation.

“Each business place had a list of these petitioners, and, if your name was on there, you were fired, and you weren’t allowed to buy food in the grocery stores in that town. You couldn’t buy gas for your car,” she said.

Celestine Parson Lloyd, left, and sister-in-law Annie Camacho look at her nearly 70-year-old test from Dr. Kenneth Clark’s famous doll experiment. Researchers at the University of South Carolina Center for Civil Rights History discovered the test at the Library of Congress and presented it to her on Jan. 15.

In 1951, the parents appealed to the Supreme Court. Although it was the first of the school desegregation cases to reach the court, it was placed behind the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education case, possibly because of the maneuvering of South Carolina Gov. James Byrnes. On May 17, 1954, the Parsons family, the Briggs family, and dozens of other unflinching South Carolinians were vindicated with the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision ruling segregation unconstitutional.

“When I got home from school, word was around,” she recalled. “My parents were elated, ‘We won! We won!’ The battle is almost over.”

Ms. Parson Lloyd graduated from Scott’s Branch High School in 1956 and departed for New York City, where she and her mother joined her father who fled Summerton amid repeated threats after the 1954 ruling. In New York, she worked on behalf of the poor and marginalized, retiring as an assistant superintendent of a women’s homeless shelter.

“By showing Civil Rights veterans the documents already preserved, we can help them recover memories. In turn, by recording their memories, we expand the history available to scholars and students,” Civil Rights Center Director Dr. Bobby Donaldson said. “We seek to document our state’s deep Civil Rights history, like the Briggs case—with donations of letters, photographs, newspapers—and to assist those who participated in historic events in chronicling their own histories.”

The Center for Civil Rights History and Research chronicles, preserves, and shares South Carolina’s vital history through community programs such as the “Recovering Untold Stories” panel, the “Justice for All” exhibit, and educational support that informs K-12 and higher education curriculum in the state. The Center was founded in November 2015 with the receipt of the congressional papers of Representative James E. Clyburn, the state’s first African-American member of Congress since the late nineteenth century and a veteran of the Civil Rights Movement. The Center’s website is located at www.civilrights.sc.edu.

#NNPA BlackPress

LIHEAP Funds Released After Weeks of Delay as States and the District Rush to Protect Households from the Cold

BLACKPRESSUSA NEWSWIRE — The federal government has released $3.6 billion in home heating assistance after a delay that left states preparing for the start of winter without the program’s annual funding.

By Stacy M. Brown

Black Press USA Senior National Correspondent

The federal government has released $3.6 billion in home heating assistance after a delay that left states preparing for the start of winter without the program’s annual funding. The Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program, known as LIHEAP, helps eligible households pay heating and cooling bills. The release follows a shutdown that stretched 43 days and pushed agencies across the country to warn families of possible disruptions.

State officials in Minnesota, Kansas, New York, and Pennsylvania had already issued alerts that the delay could slow the processing of applications or force families to wait until December for help. In Pennsylvania, more than 300,000 households depend on the program each year. Minnesota officials noted that older adults, young children, and people with disabilities face the highest risk as temperatures fall.

The delay also raised concerns among advocates who track household debt tied to rising utility costs. National Energy Assistance Directors Association Executive Director Mark Wolfe said the funds were “essential and long overdue” and added that high arrearages and increased energy prices have strained families seeking help.

Some states faced additional pressure when other services were affected by the shutdown. According to data reviewed by national energy advocates, roughly 68 percent of LIHEAP households also receive nutrition assistance, and the freeze in multiple programs increased the financial burden on low-income residents. Wolfe said families were placed in “an even more precarious situation than usual” as the shutdown stretched into November.

In Maryland, lawmakers urged the Trump administration to release funds after the state recorded its first cold-related death of the season. The Maryland Department of Health reported that a man in his 30s was found outdoors in Frederick County when temperatures dropped. Last winter, the state documented 75 cold-related deaths, the highest number in five years. Rep Kweisi Mfume joined more than 100 House members calling for immediate federal action and said LIHEAP “is not a luxury” for the 100,000 Maryland households that rely on it. He added that seniors and veterans would be placed at risk if the program remained stalled.

Maryland Gov. Wes Moore used $10.1 million in state funds to keep benefits moving, but noted that states cannot routinely replace federal dollars. His administration said families that rely on medical equipment requiring electricity are particularly vulnerable.

The District of Columbia has already mapped out its FY26 LIHEAP structure in documents filed with the federal government. The District’s plan shows that heating assistance, cooling assistance, weatherization, and year-round crisis assistance operate from October 1 through September 30. The District allocates 50 percent of its LIHEAP funds to heating assistance, 10 percent to cooling, 13 percent to year-round crisis assistance, 15 percent to weatherization, and 10 percent to administrative costs. Two percent is used for services that help residents reduce energy needs, including education on reading utility bills and identifying energy waste.

The District’s plan lists a minimum LIHEAP benefit of $200 and a maximum of $1,800 for both heating and cooling assistance. Crisis benefits are provided separately and may reach up to $500 when needed to resolve an emergency. The plan states that a household is considered in crisis if it has been disconnected from energy service, if heating oil is at 5 percent or less of capacity, or if the household has at least $200 owed after the regular benefit is applied.

The District’s filing notes that LIHEAP staff conduct outreach through community meetings, senior housing sites, Advisory Neighborhood Commissions, social media, posters, and mass mailings. The plan confirms that LIHEAP applicants can apply in person, by mail, by email, or through a mobile-friendly online application and that physically disabled residents may request in-home visits.

As agencies nationwide begin distributing the newly released funds, states continue working through large volumes of applications. Wolfe said LIHEAP administrators “have been notified that the award letters have gone out and the states can begin to draw down the funds.”

#NNPA BlackPress

Seven Steps to Help Your Child Build Meaningful Connections

BLACKPRESSUSA NEWSWIRE — Swinging side by side with a friend on the playground. Sharing chalk over bright, colorful sidewalk drawings. Hiding behind a tree during a spirited game of hide-and-seek. These simple moments between children may seem small, but they matter more than we think

By Niyoka McCoy, Ed.D., Chief Learning Officer, Stride/K12

Swinging side by side with a friend on the playground. Sharing chalk over bright, colorful sidewalk drawings. Hiding behind a tree during a spirited game of hide-and-seek. These simple moments between children may seem small, but they matter more than we think: They lay the foundation for some of life’s most important skills.

Through everyday play, young children begin learning essential social and emotional skills like sharing, resolving conflicts, showing empathy, and managing their emotions. These social skills help shape emotional growth and set kids up for long-term success. Socialization in early childhood isn’t just a “nice-to-have”—it’s essential for development.

Yet today, many young children who haven’t yet started school aren’t getting enough consistent, meaningful interaction with peers. Research shows that there’s a decline in active free play and peer socialization when compared to previous generations.

There are many reasons for this. Children who are home with a parent during the day may spend most of their time with adults, limiting opportunities for peer play. Those in daycare or preschool may have restricted free play, and large classrooms can reduce supervision and social coaching. Some children live in rural areas, are homebound due to illness, have full schedules, or rely on screens to fill their playtime. And for some families, finding other families with young children to connect with isn’t easy.

While these challenges can feel significant, opportunities for connection still exist in every community. Families can take simple steps to help children build friendships, create a sense of belonging, and strengthen social skills. Here are some ideas to get started:

- Storytime sessions at libraries or local bookstores

- Community offerings such as parent-child workshops, art, music, gymnastics, swimming, or sports programs

- Weekly events at children’s museums, which may include art projects, music workshops, or science experiments

- Outdoor exploration, where kids can play with peers

- Local parenting groups that organize playdates and group activities

- Volunteer opportunities where children can participate, such as pet adoption events or packing meals at a food bank

- Classes for kids at local businesses, including hardware, grocery, or craft stores

Some of these community activities are free or low-cost and give kids the chance to build friendships and practice social skills. Parents can also model positive social behavior by interacting with other parents and encouraging their children to play with their peers.

These may seem like small moments of connection, but they can have a powerful impact. Every time your child shares a toy, plays make-believe with peers, or races a friend down the slide, they’re not just playing—they’re learning the skills that build confidence, empathy, and lasting friendships. And it’s good for you, too. Creating intentional opportunities for play also helps you strengthen your own network of parents who can support one another as your children grow together.

#NNPA BlackPress

Seven Steps to Help Your Child Build Meaningful Connections

BLACKPRESSUSA NEWSWIRE — Swinging side by side with a friend on the playground. Sharing chalk over bright, colorful sidewalk drawings. Hiding behind a tree during a spirited game of hide-and-seek. These simple moments between children may seem small, but they matter more than we think

By Niyoka McCoy, Ed.D., Chief Learning Officer, Stride/K12

Swinging side by side with a friend on the playground. Sharing chalk over bright, colorful sidewalk drawings. Hiding behind a tree during a spirited game of hide-and-seek. These simple moments between children may seem small, but they matter more than we think: They lay the foundation for some of life’s most important skills.

Through everyday play, young children begin learning essential social and emotional skills like sharing, resolving conflicts, showing empathy, and managing their emotions. These social skills help shape emotional growth and set kids up for long-term success. Socialization in early childhood isn’t just a “nice-to-have”—it’s essential for development.

Yet today, many young children who haven’t yet started school aren’t getting enough consistent, meaningful interaction with peers. Research shows that there’s a decline in active free play and peer socialization when compared to previous generations.

There are many reasons for this. Children who are home with a parent during the day may spend most of their time with adults, limiting opportunities for peer play. Those in daycare or preschool may have restricted free play, and large classrooms can reduce supervision and social coaching. Some children live in rural areas, are homebound due to illness, have full schedules, or rely on screens to fill their playtime. And for some families, finding other families with young children to connect with isn’t easy.

While these challenges can feel significant, opportunities for connection still exist in every community. Families can take simple steps to help children build friendships, create a sense of belonging, and strengthen social skills. Here are some ideas to get started:

- Storytime sessions at libraries or local bookstores

- Community offerings such as parent-child workshops, art, music, gymnastics, swimming, or sports programs

- Weekly events at children’s museums, which may include art projects, music workshops, or science experiments

- Outdoor exploration, where kids can play with peers

- Local parenting groups that organize playdates and group activities

- Volunteer opportunities where children can participate, such as pet adoption events or packing meals at a food bank

- Classes for kids at local businesses, including hardware, grocery, or craft stores

Some of these community activities are free or low-cost and give kids the chance to build friendships and practice social skills. Parents can also model positive social behavior by interacting with other parents and encouraging their children to play with their peers.

These may seem like small moments of connection, but they can have a powerful impact. Every time your child shares a toy, plays make-believe with peers, or races a friend down the slide, they’re not just playing—they’re learning the skills that build confidence, empathy, and lasting friendships. And it’s good for you, too. Creating intentional opportunities for play also helps you strengthen your own network of parents who can support one another as your children grow together.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 12 – 18, 2025

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoIN MEMORIAM: William ‘Bill’ Patterson, 94

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoHow Charles R. Drew University Navigated More Than $20 Million in Fed Cuts – Still Prioritizing Students and Community Health

-

Bay Area4 weeks ago

Bay Area4 weeks agoNo Justice in the Justice System

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoBeyoncé and Jay-Z make rare public appearance with Lewis Hamilton at Las Vegas Grand Prix

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoLewis Hamilton set to start LAST in Saturday Night’s Las Vegas Grand Prix

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 19 – 25, 2025

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoThe Perfumed Hand of Hypocrisy: Trump Hosted Former Terror Suspect While America Condemns a Muslim Mayor