Arts and Culture

Ella Baker Legacy Energizes Movement for Black Lives

Part 1

Ella Baker was 61 years old when her comrade, historian Howard Zinn, wrote in “SNCC: The New Abolitionists,” “Ella Baker is more responsible than any other single individual for the birth of the new abolitionists as an organized group, and who remains the most tireless, most modest, and wisest activist I know in the struggle for human rights.”

In a recent talk, Cornel West said: “There is no civil rights movement without the witness and example of Ella Baker.”

Ella Baker, however, has yet to receive full, mainstream public recognition for her contribution to American democracy, especially the co-founding and guidance of the most effective, innovative civil rights organization of the 20th century, the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee—SNCC.

While it is true that the media demonizes Malcolm X and sanitizes Dr. King, Ella Baker, a Black woman, is simply ignored.

In her new book, “FROM #Blacklivesmatter to Black Liberation,” Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor writes: “Black women have been central to every significant campaign for Black rights and freedom. Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Diane Nash…were critical to the development of the civil rights movement, but that movement is still primarily known by its male leaders.”

Ella Baker was three decades older (She was called a “middle-aged hell-raiser”), but young activists trusted her because she showed more confidence in the audacity and inventiveness of youth than in the expertise of established civil rights organizations. The students affectionately called her “Miss Baker” (though she was married).

Her nickname was “Fundi,” a Swahili term for a person who hands down skills and wisdom from one community to another. Baker defied stereotypes. She was a militant revolutionary who wore elegant hats and dressed as if she were attending church.

The founding of SNCC at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1960 changed the tone and direction of the civil rights movement. The conference, which drew hundreds of students from throughout the South, was tense.

Male leaders in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference wanted to oversee the fledgling organization, to put SNCC under their control. Baker was the only woman to speak at the Plenary Session. She warned students against bureaucracy and co-optation.

She insisted on the autonomy of the students, who had already demonstrated their brilliance and savvy tactics in the early sit-ins. “I knew that young people were the hope of any movement. It was just a normal thing to me,” Baker said years later.

Each generation offers a new lens through which to view the contours of the future.

Baker’s democratic, grassroots practice permeated SNCC. By shifting the focus from appeals to the elite to organizing the disenfranchised and the poor, SNCC changed the center of gravity in the movement. Black communities were not helpless.

They were ready to fight. Mississippi historian John Dittmer wrote: “Not since Reconstruction had anyone seriously proposed that illiterate sharecroppers had the same right to the franchise as did teachers, lawyers, and doctors.”

Mentored by Baker, SNCC turned away from charismatic, top-down leaders to group-centered leadership. And it put direct, mass action at the center of strategy. SNCC students organized new sit-ins at segregated facilities, carried out the historic freedom rides in the face of violence, and registered black voters in defiance of the Ku Klux Klan in rural Mississippi.

SNCC’s assault on Jim Crow in the 60s did more to abolish the legal apparatus of white supremacy than years of well-financed legalistic and professionally run campaigns.

SNCC’s influence extended far beyond black communities in the South. Tom Hayden participated in SNCC meetings and actions, and he saw “participatory democracy” in action before he wrote the SDS Port Huron Statement. In the SDS Bulletin he asked: “Can the methods of SNCC be applied to the North?”

Paul Rockwell is a Writer-activist in the San Francisco Bay Area.His essays have appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle, Sacramento Bee, Baltimore Sun, Utne Reader, The Nation, and a host of alternative weeklies.

Activism

Essay: Intentional Self Care and Community Connections Can Improve Our Wellbeing

At the deepest and also most expansive level of reality, we are all part of the same being, our bodies made from the minerals of the earth, our spirits infused by the spiritual breath that animates the universe. Willingness to move more deeply into fear and pain is the first step toward moving into a larger consciousness. Willingness to move beyond the delusion of our separateness can show us new ways of working and living together.

By Dr. Lorraine Bonner, Special to California Black Media Partners

I went to a medical school that was steeped in the principles of classical Western medicine. However, I also learned mindfulness meditation during that time, which opened me to the multifaceted relationship between illnesses and the interconnecting environmental, mental and emotional realities that can impact an individual’s health.

Therefore, when I began to practice medicine, I also pursued training in hypnosis, relaxation techniques, meditation, and guided imagery, to bring a mind-body focus to my work in medical care and prevention.

The people I saw in my practice had a mix of problems, including high blood pressure, diabetes, and a variety of pain issues. I taught almost everyone relaxation breathing and made some general relaxation tapes. To anyone willing, I offered guided imagery.

“My work embraced an approach to wellness I call “Liberatory Health” — one that not only addresses the treatment and management of disease symptoms but also seeks to dismantle the conditions that make people sick in the first place.”

From my perspective, illness is only the outermost manifestation of our efforts to cope, often fueled by addictions such as sugar, tobacco, or alcohol, shackled by an individualistic cult belief that we have only ourselves to blame for our suffering.

At the deepest and also most expansive level of reality, we are all part of the same being, our bodies made from the minerals of the earth, our spirits infused by the spiritual breath that animates the universe. Willingness to move more deeply into fear and pain is the first step toward moving into a larger consciousness. Willingness to move beyond the delusion of our separateness can show us new ways of working and living together.

To put these ideas into practical form, I would quote the immortal Mr. Rogers: “Find the helpers.” There are already people in every community working for liberation. Some of them are running for office, others are giving food to those who need it. Some are volunteering in schools, libraries or hospitals. Some are studying liberation movements, or are working in urban or community gardens, or learning to practice restorative and transformative justice, or creating liberation art, music, dance, theater or writing. Some are mentoring high schoolers or apprenticing young people in a trade. There are many places where compassionate humans are finding other humans and working together for a better world.

A more compassionate world is possible, one in which we will all enjoy better health. Creating it will make us healthier, too.

In community, we are strong. Recognizing denial and overcoming the fragmenting effects of spiritual disorder offer us a path to liberation and true health.

Good health and well-being are the collective rights of all people!

About the Author

Dr. Lorraine Bonner is a retired physician. She is also a sculptor who works in clay, exploring issues of trust, trustworthiness and exploitation, as well as visions of a better world.

Activism

A Call to Save Liberty Hall: Oakland’s Beacon of Black Heritage Faces an Uncertain Future

For generations, Liberty Hall has been more than bricks and wood — it has been a spiritual and cultural sanctuary for Black Oakland. The building once served as a hub for Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), where Garvey’s call for economic independence and Pan-African unity resonated through the hearts of a people newly migrating to the West in search of freedom and dignity.

Special to The Post

On a quiet corner near the West Oakland BART Station stands a weathered but proud monument to African American history — the Universal Negro Improvement Association’s Liberty Hall, also known as the Marcus Garvey Building. Built in 1877, this two-story Italianate landmark has witnessed more than a century of struggle, self-determination, and community empowerment. Now, its survival hangs in the balance.

For generations, Liberty Hall has been more than bricks and wood — it has been a spiritual and cultural sanctuary for Black Oakland. The building once served as a hub for Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), where Garvey’s call for economic independence and Pan-African unity resonated through the hearts of a people newly migrating to the West in search of freedom and dignity.

Local 188 of UNIA was the largest chapter in Northern California when the organization bought the building in 1925, but a fire burned the roof in 1931, and the chapter sold the building in 1933. The International Peace Movement, founded by Father Divine, used the building through the 1950s.

Since then, the building has been a meeting ground for civil rights organizers, artists, and educators like Overcomers With Hope who have carried that same flame of liberation through Oakland’s turbulent decades.

Today, local cultural organizer and artist Douglas “Pharoah” Stewart has stepped forward to lead the charge to save Liberty Hall. Stewart is already facing “Cultural Eviction” at the Oakland Cannery, and through his organization, Indigenous House, Stewart has rallied a coalition of artists, educators, historians, and community leaders to preserve and restore the site as a community-owned cooperative center — a place where arts, wellness, and economic empowerment can thrive for future generations.

“Liberty Hall is not just a building — it’s a living ancestor,” Stewart says. “This space gave birth to movements that shaped who we are as a people. If we lose this, we lose a piece of our soul.”

Stewart envisions transforming the historic landmark into a multi-purpose cooperative hub — complete with a cultural museum, community performance space, youth tech labs, and creative studios for local entrepreneurs. His vision echoes Garvey’s own: “A place where we can rise together, economically, spiritually, and culturally.”

But the fight is urgent. The aging building faces structural challenges, and time is running short to secure preservation funding. Stewart and his team are now calling on city officials, foundations, athletes, and celebrities to join forces with the community to raise the necessary capital for acquisition and restoration.

“We’re inviting everyone — from the Oakland A’s to local artists, from Golden State Warriors players to Black-owned businesses — to stand with us,” Stewart urges. “Let’s make Liberty Hall a model for what preservation can look like when the people lead.”

The Liberty Hall Project aligns with Oakland’s growing movement to protect historic Black cultural sites — places like Esther’s Orbit Room, Marcus Bookstore, and the California Hotel. For Stewart, Liberty Hall represents a chance to bridge the city’s past with its future, transforming preservation into a living, breathing act of justice.

“This is not nostalgia,” Stewart says. “This is nation-building. It’s about creating sustainable, community-owned spaces that honor our ancestors and empower our youth.”

As development pressures mount across West Oakland, Liberty Hall stands as a powerful reminder of resilience, resistance, and rebirth. The question now is whether the community — and those with the power to help — will answer the call.

For donations, partnerships, or information about the Liberty Hall Cooperative Development Project, contact Indigenous House at www.indigenoushouse.org Douglas Stewart dstewart.wealth@gmail.com

Activism

MLK Way at 57th Street in Oakland Renamed Bobby Seale Way for Black Panther Co-Founder

In 1962, Bobby Seale and Virtual Murrell cofounded the first known Black student organization called the Soul Students Advisory Council at Oakland City College located at 57th and Grove streets, now MLK. Jr. Way.

By Zac Unger

We are so proud to honor the legacy of the great Bobby Seale by commemoratively renaming 57th Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Way to Bobby Seale Way in North Oakland. Seale, 88, has dedicated his life to advancing social justice, racial equality, and community self-determination. He played an essential part in the history of our country by co-founding the Black Panther Party for Self Defense in Oakland in 1966 with the late Huey Newton.

Our City has a tremendous history of activism, and it is a legacy we are proud of and strive to continue as our community and country face so many incredible challenges right now.

In 1962, Bobby Seale and Virtual Murrell cofounded the first known Black student organization called the Soul Students Advisory Council at Oakland City College, located at 57th and Grove streets, now MLK. Jr. Way.

Later, they cofounded the first Negro history class, which led to the establishment of the first Black Studies program in college curricula in the country. Murrell is scheduled to introduce Seale at the street dedication.

The author of “Seize the Time,” Seale ran for mayor of Oakland in 1973, coming in second in a field of nine. We are proud to memorialize his legacy by renaming this street so that we do not forget the legacy and change he has made.

Zac Unger is Oakland’s District 1 Councilmember

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 12 – 18, 2025

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoIN MEMORIAM: William ‘Bill’ Patterson, 94

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoHow Charles R. Drew University Navigated More Than $20 Million in Fed Cuts – Still Prioritizing Students and Community Health

-

Bay Area4 weeks ago

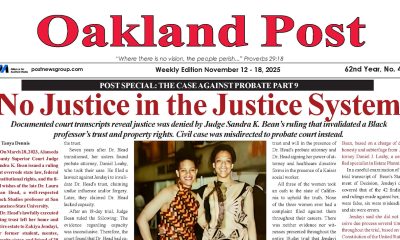

Bay Area4 weeks agoNo Justice in the Justice System

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoLewis Hamilton set to start LAST in Saturday Night’s Las Vegas Grand Prix

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoBeyoncé and Jay-Z make rare public appearance with Lewis Hamilton at Las Vegas Grand Prix

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 19 – 25, 2025

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoThe Perfumed Hand of Hypocrisy: Trump Hosted Former Terror Suspect While America Condemns a Muslim Mayor